Purple Magazine

— F/W 2013 issue 20

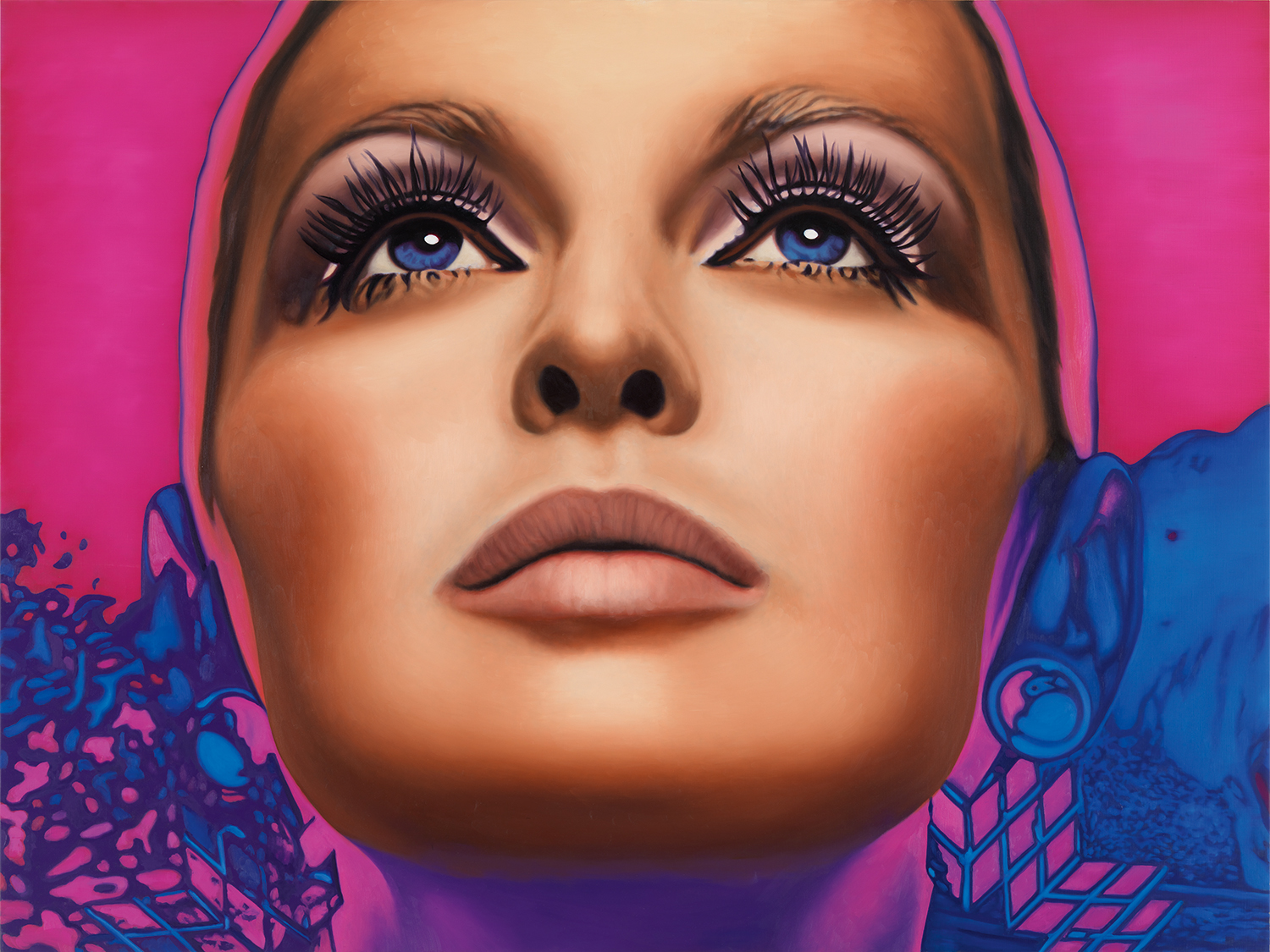

Richard Phillips

Endless, 2013, oil on canvas<br />Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery

Endless, 2013, oil on canvas<br />Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery

on guy stuff

interview by SABINE HELLER

portrait by RICHARD KERN

The American painter Richard Phillips is known for his glossy, hyperrealist portraits of sometimes-controversial celebrities and iconic women drawn from found imagery. He also has an uncomfortably close relationship with pop culture, having done a cameo on Gossip Girl and collaborated with a myriad of fashion and cosmetics brands, including Jimmy Choo and MAC. Recently, Phillips — who paints with the skill of a master — has started to explore filmmaking and photography while returning to sculpture, a form through which he quickly gained recognition in the ’80s New York art world.

SABINE HELLER — Tell me about your youth.

RICHARD PHILLIPS — I grew up in the suburban Boston town of Marblehead, in the 1960s and ’70s. I’m the same age…