Purple Magazine

— S/S 2014 issue 21

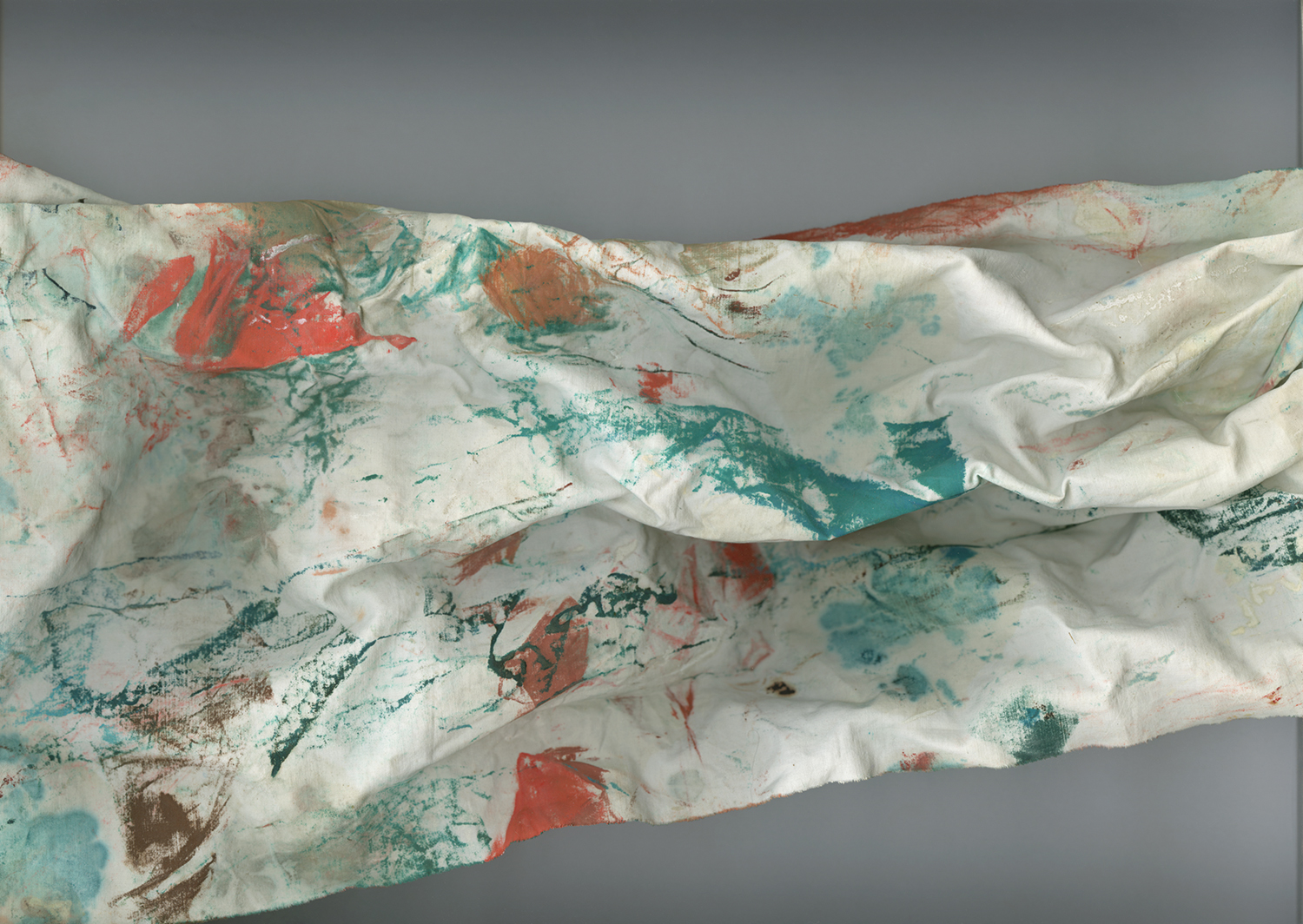

The Inventory of Balthus

Le Tablier de Balthus

Le Tablier de Balthus

For the last 24 years of his life, the French painter Balthus, born Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, lived high up in the remote Swiss village of Rossinière. The house where he lived, The Grand Chalet, is one of the largest wooden structures of its kind in Europe. Balthus’s studio is located there and has remained intact since his death in 2001.

Artist Katerina Jebb was commissioned by the Balthus family to document the contents of his studio. Seen here are several objects from the hundreds that Jebb photographed with a scanner over a period of three years. The BALTHUS INVENTORY will be exhibited as part of the painter’s retrospective at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum in April 2014.

photography by KATERINA JEBB

text by GUIDO BRIVIO

translation by JONATHAN FISCHNALLER

Oil Paint on Cotton Rag

Oil Paint on Cotton Rag

We…

-

Pigment on Cotton

-

Eyeglasses

-

La Nature est Plus Belle Sans L’Homme