Purple Magazine

— S/S 2013 issue 19

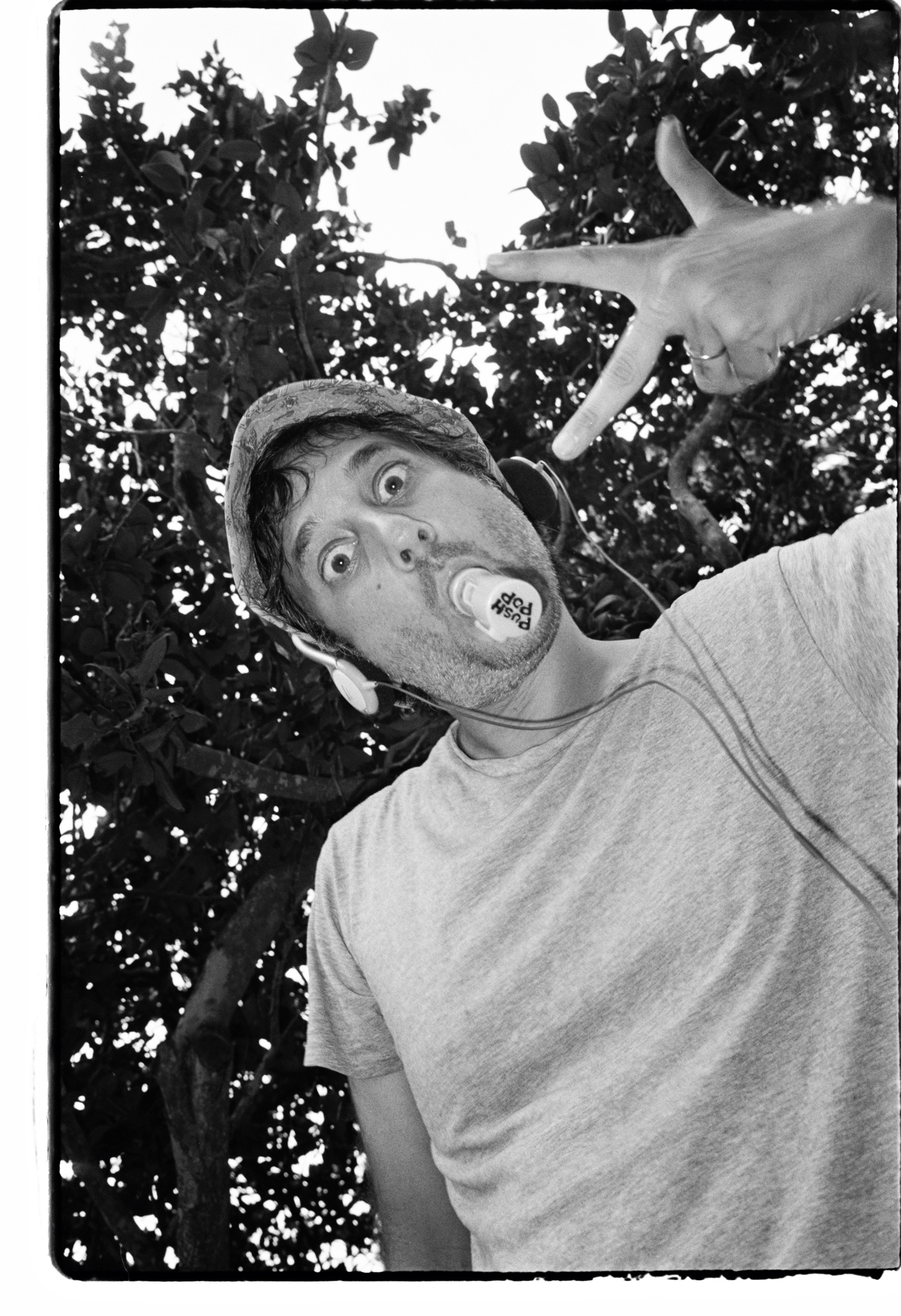

Harmony Korine

spring breakers

interview and photography by ANNABEL MEHRAN

It’s been two decades since a 19-year-old Harmony Korine wrote the critically acclaimed screenplay for Larry Clark’s film Kids. Since then, he has written, directed, and produced a wide-ranging body of books, screenplays, and films. For the underground community of artists, his body of work composes a masterpiece. And yet he has never achieved mass-market success — even though, in 2009, Harmony won the Copenhagen International Documentary Film Festival’s prestigious DOX Award for his film Trash Humpers, which he wrote and directed. With his fourth feature film, Spring Breakers, Harmony hasn’t lowered his artistic standards. But with this film, by making what he calls a “pop movie” — and casting Disney favorites and teen stars Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens, and Ashley Benson, along with the prolific James Franco, and shooting them all under the Florida sun — he clearly decided to…