Purple Magazine

— S/S 2012 issue 17

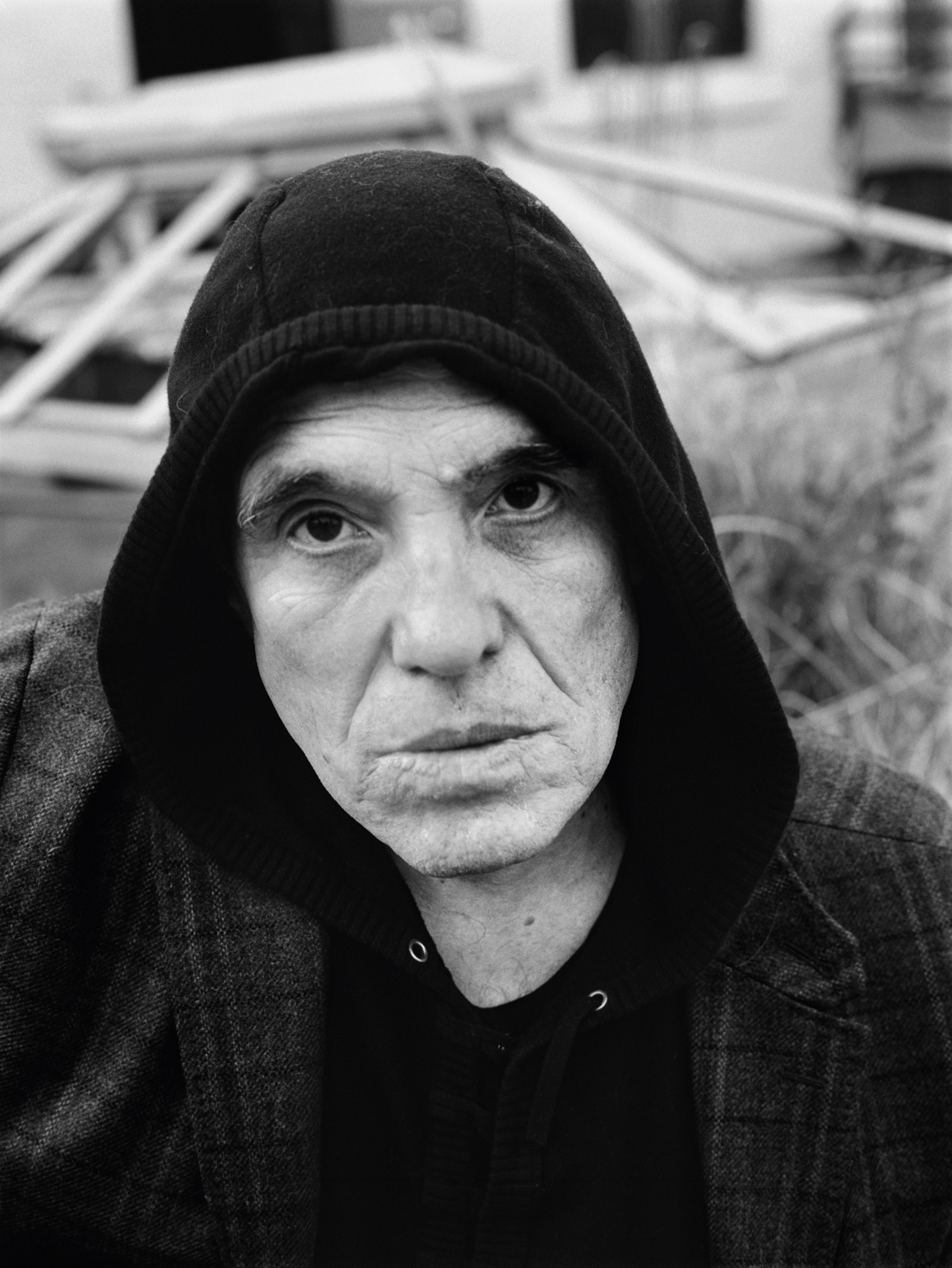

Abel Ferrara

a conversation with Spencer Sweeney

interview by SPENCER SWEENEY

photography by ANNABEL MEHRAN

Abel Ferrara’s new film, 4:44 — Last Day on Earth, is about the apocalypse. It stars Willem Dafoe and Ferrara’s longtime companion, Shanyn Leigh, and was shot by his longtime cinematographer, Ken Kelsch. In the film, Leigh plays the role of a painter. Spencer Sweeney, the New York artist who prepared this interview for Purple, did the actual paintings in the film, which comes out this year.

SPENCER SWEENEY — Sometimes when I’m working on a painting, it starts to take a direction. But maybe I’ll want to do a 180-degree turn-around, cover the whole thing up, and start over. The experience can lead to a decision that becomes part of it, right up to the end.

ABEL FERRARA — Exactly. The painting you did for the movie was a process. The under-painting is…