Purple Magazine

— The Cosmos Issue #32 F/W 2019

philippe parreno

art PHILIPPE PARRENA

a cephalopod aquarium in an artist’s studio with a cuttlefish for a friend: man and mollusk engage in a cosmic dialogue on film, pushing the frontiers of art

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

portraits BY OLA RINDAL

OLIVIER ZAHM — Anywhen is a film about the cuttlefish that lived in your aquarium?

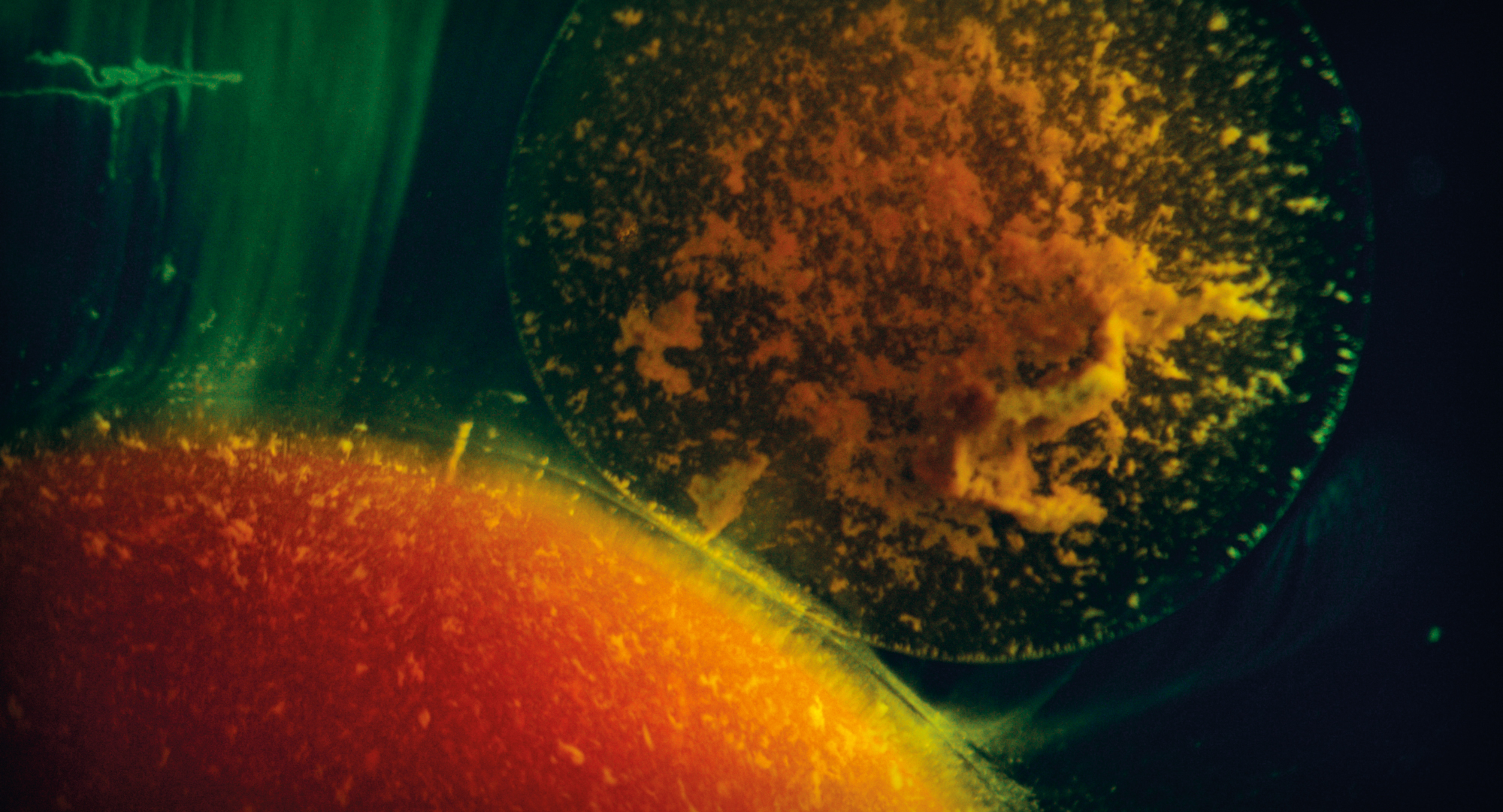

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yes. It’s a cinematographic portrait of an animal. All of the documentary aspects are there: the close-up, the voice-over, and so forth. But the voice is strange, as it was recorded by the ventriloquist Nina Conti. She tries to make the image speak — and the constantly changing colors of the cuttlefish, with the chromatophores, turn into the image’s pixels, as it were. It’s as if the image itself were speaking.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s as if the cuttlefish were changing the colors of the image.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Right, and the closer you get to it with the camera, the closer it moves toward the camera because it’s a very curious person. It comes right up to you when you look at it — and stares. The text in the film is about relationships and reciprocity between persons, some of whom happen to be nonhuman.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Because the cuttlefish is an almost primitive life-form, which camouflages or blends in with the image and with language…

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Instead of using a word to qualify something, you become the thing itself, as in the virtual world. In a virtual world, nothing prevents you from becoming a cuttlefish. You select your avatar and morph into it. So, you don’t need words. You bypass the symbol to become the thing itself.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Does language become the reality of the exhibition?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — My interest in an exhibition lies more in the arrangement of objects than in the objects themselves.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your exhibitions are living organisms, with their own rhythm and pulse. The scientific aquarium in your studio is a metaphor for that. You’ve set up a micro-ecosystem with real plants and microorganisms…

PHILIPPE PARRENO — And the oceanographic laboratory of Paris visits regularly: some of our cuttlefish have laid eggs, and they’ve taken them in hand. I do it strictly as an amateur, but it’s become a kind of obsession.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do cuttlefish live short lives?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — They live for two years. They’re highly intelligent creatures, but they have a limited lifespan, and they also happen to be among the most difficult animals to breed in an aquarium. It’s got nothing to do with me. They’re punished by god. And now we have a baby octopus. It’s very intelligent, insofar as it can respond very quickly to complicated questions and situations, simply through observation. For example, if you put a crab in a closed jar, it’ll open the jar. You show the crab how to do it once, and it understands which way to turn the lid… It’s crazy. You’ve got to give it toys because it gets bored fast. You give it baby toys so it can feel different textures — because it’s very curious. If you put your hand in, it’ll grab your hand and taste you. And it’ll recognize you… It’s very odd developing a relationship with something that doesn’t breathe the same air as you do. It’s like the relationship you might have with an alien. We’re not subject to the same laws.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Is your fascination with all this also a form of inquiry?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yes, and it entails daily observation. Let’s say it’s become a studio practice to look at the octopus, observe it, communicate with it. I take care of it every day and clean the aquarium. It’s astonishing to see how I’ve come to develop a relationship with these rather strange animals. I find it all a bit sci-fi.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What do you seek in these images of a marine animal — images that recall those of outer space, actually?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — I seek the loss of scale, to be confronted with the unknown. It’s a true production of images in the sense that the more you look at the being, the more it looks at you. That’s the very odd thing about it. It loves the attention, and the more attentive you are, the more it looks.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Divers often observe the same thing… All your exhibitions have a spectral aspect. We enter a space that isn’t known or identified — like a gallery space, a wall for hangings, or even a performance space. Your retrospective exhibition in Porto [Portugal], “A Time Colored Space,” already established a link between space and time. And you colorized it as well. Does your inquiry into space and time serve as an exhibition’s process or as its language?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — It advances the notion of the exhibition as a physical patch of spacetime. The exhibition in Berlin [an untitled one at the Gropius Bau in 2018] was like an organism insofar as the whole space was controlled by a living colony of yeasts that generated sounds. I set up a basin and a bioreactor, with mics that generated interference. The idea was to program the exhibition’s temporality through a series of events in the space. Instead of having it vary by means of a mathematical algorithm, I tried to have it move with respect to life itself. The idea was to sort of reproduce what [John] Cage did when he composed music using the I-Ching [The Book of Changes]. To produce nonperiodic events, with the idea that things repeat themselves but never in exactly the same way.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The aleatory aspect of life.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yes, a form of life. All the perspectives shift with the rise and fall of curtains. The space would change completely, but in a fairly simple way, with just the variation of daylight.

OLIVIER ZAHM — We might say that your exhibitions are more environments or microcosms.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — I see them more as creatures.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Because, in a sense, they’re a path into the unknown, a complete departure from what we expect from an exhibition.

PHILIPPE PARRENO – Yes. I’m moving away from the display of objects. An object is just a medium that allows you to organize something much bigger.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The objects here are nothing more than the stones in an aquarium.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Exactly. I conceived the exhibition in Berlin around a large artificial pond. Like any other organism, it needs water to function. There were two movie theaters on one side, which were like the creature’s two eyes. On the west side, filters tinted the space orange, producing a sort of perpetual dusk. The loudspeakers were connected to the exterior space, so the sounds of the city might or might not enter the exhibition. In any case, the space was acoustically transparent. And the yeast — which every organism generates or digests — was in fact the exhibition’s creatural digestion.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Like creatures that have their own rhythm, their own breath, sleep, withdrawal, and contact. Creatures that we’ve always seen as dangers or threats — which is absurd because our whole ecosystem is a gigantic creature with multiple points of entry.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Of course. And one that contains us. We now know that we’re not delimited by the contours of our skin. We’re always irradiating and breathing in other things that do the same.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Cosmic particles from the dawn of the universe — nanoparticles that are present in the environment — pass through us like X-rays. We are ourselves made up of the universe’s originary particles.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — We are spectral. And a specter is a figure that’s hard to delimit.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where does this fascination with the nonhuman come from? The fascination with mechanical processes and artificial intelligence?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — At the exhibition I did a few weeks ago in New York, at Barbara Gladstone’s, I showed Anywhen, but I didn’t show it in a loop, where the film would end and start again at the beginning. I thought it’d be interesting for the computer, which is the player, to gradually try to remember what it had shown. We worked with artificial intelligence and neural network algorithms to try to find a way for the computer player to remember the film.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So that it would also forget part of it?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — So that the film could be reconstituted by an artificial intelligence. At the end of the exhibition, it would, in principle, be able to reconstruct it entirely. The first attempts were very odd.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In the beginning, it would remember partially, and then, with repetition, it would gradually refine things.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — In the beginning, the computer would remember the colors. It would get the water and the skin of the cephalopods rather quickly. Then, at a certain point, it would start getting the form. Then the image would become less blurry. Then the voice would evolve, too, from a sort of electronic wind, like musique concrète, to an articulate voice.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, the rhythm of the projection was affected by the machine’s capacity to remember what it had already shown and reconstitute it via artificial intelligence.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — The algorithm would essentially determine what was going to happen next. It’s a weird kind of memory, a reading memory. We’d feed it an image, and it would predict the next image. It would try to anticipate. That’s the way it would remember. What I found amusing was the confrontation between a creature, the cuttlefish, and two nonhuman creatures — a film and artificial intelligence — looking at each other and, in the same way, reflecting each other. Like an echo.

OLIVIER ZAHM — As an artist, what’s your view on technology’s evolution? Do you see it as a danger or as a new environment where we’re going to live without anxiety? You are increasingly headed in that direction, and extracting from it forms of beauty, elements of suspense, or the codification of perception. Is it a positive or negative evolution for you?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — I think there are going to be meldings of man and machine, machine and man. I’m thinking of Donna Haraway’s transformist robot in that first great text of feminist counterculture, A Cyborg Manifesto: that a robot’s identity is always shifting.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Neither completely human, nor completely machine.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Exactly. It can learn to behave like an animal or like a human. I think things are going to play out through the notion of “trans” — I’m more and more convinced of that.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Hybrid identity? And so, perhaps, not through face-to-face confrontation?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yeah. I think that’s a bit sci-fi.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Not through armed conflict between men and machines? [Laughs]

PHILIPPE PARRENO — I don’t think so. It’s not Terminator. Now, the work done by Emanuele Coccia’s metaphysics, what he was trying to see with plants — that was interesting. Right now he’s working on the idea of recycling as reincarnation. Then there’s the recent work of Carsten Höller, with The Florence Experiment, where the plants breathed fear and felt emotions.

OLIVIER ZAHM — These are hybridizations.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yes, and they get stranger and stranger because you come to the ever-clearer realization that there is communication without man — there’s communication all around us. We are not in the center of it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Maybe the destruction we’re bringing down upon the planet and the whole biosphere isn’t the end reaction of these organisms. Maybe they’ll develop defenses and adaptations that will go beyond us.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — The greatest danger, as you say, is lack of diversity. The more diverse and varied the material produced, the more history can occur, the more future there is.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You mentioned Frankenstein.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yeah. That’s the project I’m working on now.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Another creature, then — one that escapes its creator.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — It occurred to me when I was doing Marilyn. I reread Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and it touched me deeply. There’s a lot of empathy in the storytelling.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Empathy for the monster?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — It’s people who are telling one another things and who finally listen. The text is narrated by Captain Robert Walton, who takes in Victor Frankenstein, the monster’s creator, who then recounts his childhood memories… And Walton writes to his sister. So, it really does turn on empathy, friendship, and the relationship with the other.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, it’s polyphonic.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yes. There are several narrators, and there’s this very odd thing that’s been completely passed over. At one point, the creature summons its creator to the cave. It has killed people, and it says: “Before we go any further, I’d like to say something to you. Listen to me first, then judge.” The monster is extremely articulate.

OLIVIER ZAHM — He lives by a code.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Well, he doesn’t say it in those terms, but we could say it today in more modern terms: “How could you imagine what it’s like to exist without having been born?” That’s a very contemporary question. How can you exist without a past, without having been born, without having grown up? How can you judge me? And Victor Frankenstein understands. He understands so well that he tries to make a second monster, so that the creature can have a companion, a love affair. That part has been erased by the story written for the cinema.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where he scares everyone and is rejected. And the more he’s rejected, the more he rejects.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Yes, cinema always depicts the monster as an idiot, whereas in the novel he is intelligent. What I found amusing was to see how it might play out today — to tell the story from the point of view of the creature.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Which really is the formula behind artificial intelligence and artificial life, which has no origin.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — Exactly. The monster, who has never even had a name, will be the narrator of the film and tell his story. You know, Mary Shelley wrote that novel in what was called the “year without a summer.” On April 5, 1815, just before sunset, a massive explosion shook the volcanic island of Sumbawa in Indonesia. For two hours, a stream of lava erupted from Mount Tambora. This event affected the planet’s climate, resulting in a very dark year. There were famines… The monster says he comes from that climatic upheaval. The monster speaks and tells his story — his historical birth, his symbolic birth through the novel that Mary Shelley writes about Frankenstein. He’s omniscient and tells his story… So, the first question is: “Who’s going to be the monster — who’s going to play him?” The project is, in effect, to cast a dead man. We have several leads at the moment, notably a dead actor. How do you compensate a dead actor? Because he must be remunerated if he’s going to get a billing… And in the beginning, the monster speaks my words, but the further along we get, the more he’ll speak his own words because we’re going to confer artificial intelligence on him. At some point, then, he’ll not only be omniscient, but also say whatever he wants to. And when he finishes his story, he’ll be set free.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, you’d like to establish a program where you start with an existing story, but the character takes charge and then tells it his own way?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — It takes a fresh look at the question of the monstrous — and not the way cinema did it in the 1930s. The digital monster today can’t just be cut, like analog cinema, where you cut the footage to produce a creature with scars. I think it has to resemble a very beautiful engraving by Goya, Que Viene el Coco [Here Comes the Bogey Man]. The Coco was a truly wicked creature who frightened everyone but could never be seen. The only way to see it was to cover it with a white sheet. It’s the figure of the ghost. Without the sheet, it’s invisible. I think that the monstrosity that speaks will be monstrous because it’s invisible, and yet it will speak.

OLIVIER ZAHM — When will this happen?

PHILIPPE PARRENO — The filming? Next year, I hope.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s an experiment in that the script and the dialogue will get away from you, but as for the composition…

PHILIPPE PARRENO — At the same time, I’m borrowing from the exhibition the idea that I don’t tell tales. I’m borrowing from the exhibition a sort of possibility of being in relation with the image and nevertheless having a phenomenological relation to it. You enter a dark room to listen to a dead man tell you the story of a character that you recognize but who, at some point, will free himself from the story.

OLIVIER ZAHM — A story from which the character will free himself all by himself.

PHILIPPE PARRENO — That’s the exhibition: the film and the locus of the emancipation of the monstrous, of the nonhuman.

END

PORTRAITS BY OLA RINDAL

PORTRAITS BY OLA RINDAL

PHILIPPE PARRENO, ANYWHEN, 2017, 11:02 MINUTES COPYRIGHT AND COURTESY OF PHILIPPE PARRENO

PHILIPPE PARRENO, ANYWHEN, 2017, 11:02 MINUTES COPYRIGHT AND COURTESY OF PHILIPPE PARRENO

PHILIPPE PARRENO, ANYWHEN, 2017, 11:02 MINUTES COPYRIGHT AND COURTESY OF PHILIPPE PARRENO

PHILIPPE PARRENO, ANYWHEN, 2017, 11:02 MINUTES COPYRIGHT AND COURTESY OF PHILIPPE PARRENO