Purple Magazine

— The Cosmos Issue #32 F/W 2019

marie-claire daveu

sustainability MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU

there’s hope – a revolution is underway as the fashion industry looks to clean up its act

kering, the group behind brands including saint laurent, balenciaga, and gucci, has made it a top priority.

the challenge of the new decade

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

artworks by PETER SHIRE

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, we have only a decade left!

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — That’s what all the world’s climate experts say. The three major challenges are climate change, the loss of biodiversity, and the depletion of natural resources and energy sources.

OLIVIER ZAHM — We have 10 years to make up for 30 years of inaction.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — We have 10 years to set up systems to truly change our modes of consumption and production with respect to the carbon economy. It’s an immense challenge. Technical solutions exist, but we have to find a way to implement them on a large scale, both quantitatively and geographically. My job is to do it in fashion for all of Kering’s brands.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What are the main sources of pollution in the fashion and textiles sector?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — One of the foremost problems is water pollution, starting with the raw materials. Cotton, for example, requires lots of water to grow. The various dyeing and coloring production cycles also use a great deal of water, and these processes are highly polluting.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s also the problem of washing clothes, which nobody thinks about.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — It’s being raised more frequently. Part of the pollution in oceans comes from laundering clothes at home, which breaks up clothes into particles. Washing machines need to be fitted with filters to collect them. Also, the water has to be treated before being released back into the environment.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What are other sources of pollution in fashion?MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Another factor in pollution that ties in more with the climate is leather. Leather is a by-product of cattle, which release a lot of methane, a greenhouse gas whose effect on global warming is 20 times that of CO2. So, fashion brands need to look at what’s used to feed these bovines, the density of animals put out to pasture, and so forth.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Then there’s the matter of the mountains of unsold clothes.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Yes. What do we do with unsold clothes and accessories? Clearly, we have to work toward establishing a so-called circular economy. Let’s say I have a t-shirt that was produced but never sold. Rather than destroy it, I could use it to make a new product, through recycling or upcycling. This lends new value to the recycled and transformed product.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Aside from the pollution caused by the destruction of unsold products, the ecological impact of the harvesting of raw materials and of the entire production process also has to be dealt with.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Exactly. We need a holistic approach to the problem.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What percentage of fashion products are destroyed?MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — I don’t have the percentages. That’s something the companies keep to themselves. But it’s a fairly significant percentage for certain brands.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How do you keep tabs on all the suppliers and ensure that they abide by sustainable criteria?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — You have to lay down specifications, ask your suppliers to meet them, and then check to see that they’re actually being met. You put all that in the contracts. But you can’t just show up and say, “That’s the way you have to work.” First, you have to establish a strong relationship with the supplier. You need to do a little capacity-building. You have to explain why you’d like to do things another way.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In terms of urgency, the next decade will be crucial.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — It’s vital! We have to anticipate the foreseeable consequences of the disaster underway, but for some, it’s already too late. So, we have to manage it. That’s why we speak of adaptation. Then, to avoid the worst in terms of impact, we have to eliminate carbon emissions entirely, bolster biodiversity, find technological solutions, boost renewable, energy, and, most of all, limit energy consumption. The fashion sector and notably the luxury sector have an essential role to play, a special responsibility — because if a designer says something, if a fashion brand says it, if a magazine such as yours says it, then it has an impact! More than if it comes from the scientific community, which nobody really listens to. That’s why we consider that we have a responsibility to lay out not just what’s at risk, but also the solutions — and to open the way. This is [Kering chairman and CEO] François-Henri Pinault’s approach.

OLIVIER ZAHM — To bring along the entire fashion industry and its globalized production chain?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Exactly. In line with that, there’s the G7, scheduled for August in France, and Emmanuel Macronhas tasked François-Henri Pinault with rounding up the companies prepared to make environmental commitments — a coalition of companies in the fashion industry. We’re working on it now.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That’s a big deal symbolically.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — It sendsa rather powerful message.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Because fashion can raise awareness, and fashion is aimed at the young.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Yes. Fashion has a rather phenomenal ability to get things moving and raise people’s awareness. There’s real power in our brands and designers and their image. They have a huge reach.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, Kering appointed you in 2012 to move the group forward in terms of sustainability?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Yes. I arrived on September 1, 2012. It’s been almost seven years.

OLIVIER ZAHM — We can say that Kering was ahead of the curve. Personally, I’ve only really started worrying about all this over the past six months or so.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — As you know, though, the most recent converts are the most zealous, so I’m counting on you. And once we realize that we’ve turned a corner, that there’s no going back — the first thing we did was to take stock of our environmental impact.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You mean the carbon footprint?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — No. I mean something broader — the whole effect on the environment.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Is it quantifiable?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — It’s measurable. We developed a specific tool, which works on the same principle as a financial income statement, but it’s called the income statement for the environment. It measures the environmental impact of our own operations, but also that of our entire supply chain. We measure the carbon footprint, the impact on biodiversity, water consumption, the waste released into the water system. The interesting thing is that, instead of measuring things in terms of tons or hectares, for example, we give a monetary value. We express it in euros.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The cost it represents for Kering?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — No, the cost on nature! Let’s think in terms of liters of water. A liter of water consumed in Normandy won’t have the same impact on the environment as a liter of water in southern Italy or in an arid region. It’s too limiting to call it just a liter of water.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, how does that translate into euros for the planet? If I take so much water, water has such-and-such a value. If I were to return that value, I’d render such-and-such amount.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Exactly.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s as if nature were one of your suppliers.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Exactly. The best example is carbon emissions. Today, that comes at almost no cost because some countries actually have quotas, with fees of 15 euros per ton of carbon emitted. Today, capitalism is based on financial accounting, which doesn’t take into account the impact on the environment. The idea now is to set up an environmental accounting method. We began in 2011, and in 2015 we published our first income statement for the environment.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Is all this new for the industry?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — It’s a new way of thinking, and that’s why I’m calling it pragmatic ecology. First of all, it’s allowed our teams, brands, and CEO to realize that less than 10% of our environmental impact was due to our own operations: offices, stores, transport, and so forth. Up to 90% of our impact was due to our supply chain — in other words, to our suppliers! — and was therefore outside of our legal liability. So, it’s up to us to encourage or compel our suppliers to change their ways. We have to share this new mindset. One tack is to speak of it positively, to consider it a terrific opportunity to innovate and be creative.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And bring the entire production chain along with you.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Yes. Right now, we’re trying to set up a specific program for every raw material, as well as for every step in the manufacturing. Traditional leather tanning, for example, involves a highly polluting form of chromium. So, we’ve developed a tanning process that does away with heavy metals. For cashmere, we’ve set up a program in Mongolia with certain practices. We’ve done the same for wool and silk.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Don’t you feel overwhelmed? You’re describing an enormous undertaking.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU – If we want to change the paradigm, we have no choice. But we’ve got a whole team at Kering! There are 20 of us at the corporate level and 50 in the whole group. We’re a group of 40,000. The most important thing is to get top management in on it — to get François-Henri Pinault to include at least one sustainable development item on the agenda at almost every meeting of the executive committee.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Are you optimistic? Is 10 years enough time to implement all these strategies and get consumers to change as well?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — If you want to work in sustainable development, you have to be optimistic. Otherwise, it’s impossible.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Otherwise, it’s better to be blind and deaf.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — I’m realistic and pragmatic. It’s possible, but I know the clock’s ticking. In any case, we shouldn’t wait for the big change. We have to take action every which way and move forward now. We mustn’t sit around asking a thousand questions or seek out the perfect thing. We have to advance step-by-step and set up concrete programs.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And we shouldn’t be too ambitious, either?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — No. My thinking, if you want to take things to their logical conclusion, is that we should minimize our impact on the environment, and we’re trying to do that. We have to get things not down to zero — because that’s impossible — but as low as possible.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you have specific objectives or just good intentions?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — We’ve committed to reducing our environmental impact by 40% by 2025, which is right around the corner. And our greenhouse-gas emissions by 50% because that’s one of the major issues. That’s extremely ambitious.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Does it involve changing production levels?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — We’re not reversing growth, but each year we gain in efficiency. Some people may seek to reverse growth — I don’t believe in that. If you think in terms of reversing growth, you have to think on an international scale. You have to explain to other countries, to other people, that they don’t have a right to keep developing. On the other hand, they’re under no obligation to do the same stupid things that we did during our development and that we still do. It’s the notion of shared responsibility, but differentiated. When you look at China, for example, it’s very interesting. I’m not speaking about democracy, of course, but what the government is doing in terms of the environment is very impressive.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s a good sign.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — It’s also very interesting to see politically why they’re doing it. They’ve understood that one of the ways to keep social peace in the country is to address certain fundamental issues. The Chinese government has made some very strong commitments on environmental matters, whether it’s climate change, the pollution of waterways, or what have you.

OLIVIER ZAHM — They’re aware of it… So, the reversal of growth doesn’t work at the global level. We can’t prevent emerging countries and populations from wanting to achieve our standard of living, but what we can do, according to you, is work on the modalities of growth?

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — Yes, and seek other solutions for production. We ourselves are investing heavily in start-ups linked to the circular economy. [These solutions] are not yet operational. But back in 2013, we invested in one start-up, for example, that’s devised a way to separate cellulose fibers from polyester fibers in used garments. The objective is to recover these different fibers so we can make something new with them. We’re not saying that the planet’s resources aren’t to be used — only that we have to use them responsibly and restore the Earth’s ability to regenerate.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, these new possibilities give us reason to be hopeful.

MARIE-CLAIRE DAVEU — That’s why I love my job!

END

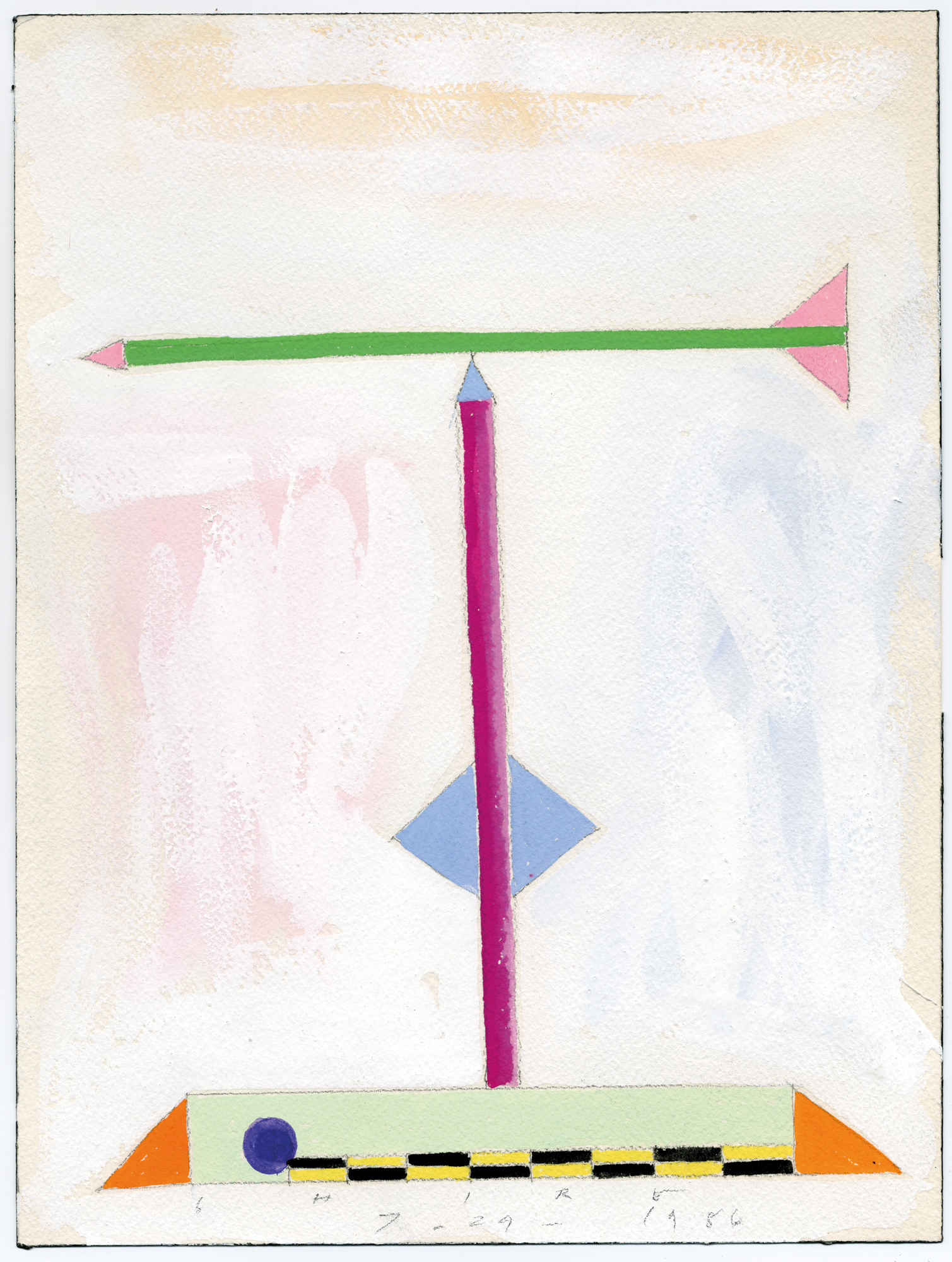

PETER SHIRE, INTER-BALLISTIC LOVE ARROW, 1986, GOUACHE, ARCHES COLD-PRESS 140 GRAM WATERCOLOR PAPER, 7 X 10 INCHES

PETER SHIRE, INTER-BALLISTIC LOVE ARROW, 1986, GOUACHE, ARCHES COLD-PRESS 140 GRAM WATERCOLOR PAPER, 7 X 10 INCHES

PETER SHIRE, THREE’S COMPANY, TWO’S A CROWD, 1986, GOUACHE, ARCHES COLD-PRESS 140 GRAM WATERCOLOR PAPER, 9 X 12 INCHES

PETER SHIRE, THREE’S COMPANY, TWO’S A CROWD, 1986, GOUACHE, ARCHES COLD-PRESS 140 GRAM WATERCOLOR PAPER, 9 X 12 INCHES

PETER SHIRE, A PLATFORM FOR LIVING CLOSER TO HEAVEN, 2015, GOUACHE ON RAG PAPER

PETER SHIRE, A PLATFORM FOR LIVING CLOSER TO HEAVEN, 2015, GOUACHE ON RAG PAPER

PETER SHIRE, YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE, 2017, GOUACHE ON RAG PAPER

PETER SHIRE, YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE, 2017, GOUACHE ON RAG PAPER