Purple Magazine

— F/W 2015 issue 24

Simon Liberati

Simon Liberati

Simon Liberati

all about Eva

interview and portrait by OLIVIER ZAHM

One of the best French literary stylists today, Simon Liberati examines life through a darkly romantic lens — he looks at shattered lives, deviant passions, unexpected destinies, illicit love, and the underbelly of glamour and social appearances. His brilliant new book, Eva, is the true love story of how his life as a writer became intertwined with his long-time obsession with Eva Ionesco, who recently became his wife. Eva is the daughter of the infamous photographer Irina Ionesco, who scandalized the world by photographing the provocatively naked preteen Eva. As a teenager, Eva became a fixture of Paris nightlife at the club Le Palace; she was the inspiration for Louis Malle’s film Pretty Baby. She herself would become a photographer and filmmaker, shooting her childhood in a film called My Little Princess. She is currently working on a new film about her Palace years. Behind Liberati’s fascinating portrait of Eva lies a profound text on human feelings and how his obsessive passion for literature converged with his unconditional love for Eva.

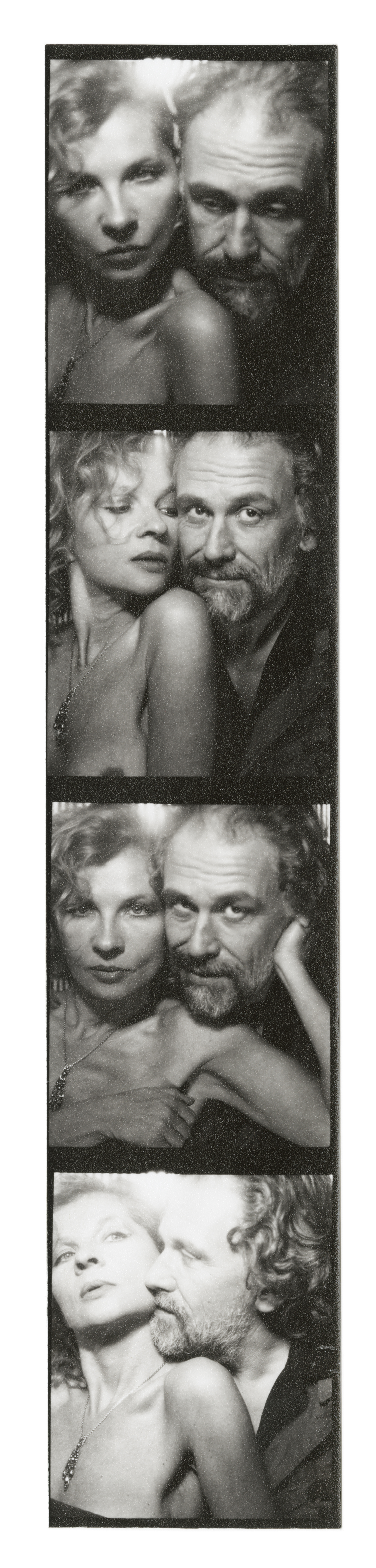

Eva Ionesco and Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 2014

Eva Ionesco and Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 2014

OLIVIER ZAHM — You were a late bloomer in literary terms.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes. I published my first novel, Anthology of Apparitions, at 44. But my life has always been filled with books, ever since childhood.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What happened earlier in life for you to start publishing so late? In a television interview in 1971, the singer Jacques Brel had some things to say on the subject. He said that you recount only your failures, only what you haven’t managed to do. Your childhood dreams. He goes on to say that man reaches completion at around the age of 16 or 17, after he’s dreamed his life and before he starts spending his time trying to realize his dreams. Giving shape to failed dreams: does that notion apply to your literary quest?

SIMON LIBERATI — Things were pretty quickly settled for me at 16 or 17, no doubt on account of a book that really struck me at that age: The Satyricon of Petronius, the first novel of debauchery in decadent Rome. The Satyricon is a pile of fragments. There’s nothing left of it, or very little: just scraps. I read it first in French, then I went so far as to translate it from Latin and studied it at the Sorbonne. I even did my master’s thesis on a grammatical point in it and the use of the demonstrative pronoun.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So it started with The Satyricon. What was it, exactly, about that book?

SIMON LIBERATI — Let’s just say that before I read the book I saw the film: Fellini Satyricon. Then I read and reread the book. What most struck me was the story, at the beginning, called “The Banquet of Trimalchio.” More specifically, the brief passage recounting the wedding of Pannychis. Pannychis is a girl of ten or eleven at a bordello, where the mistress forces her to lose her virginity and marry Giton. It’s just an amusement among libertines. For reasons unknown, the wedding of Pannychis was for me something like a tableau vivant. When I was working for ten years to try to become a painter, before I turned to writing instead, it was one of the scenes that fascinated me. Later, I ended up writing a literary description of it, which I think I inserted into my novel L’Hyper Justine. There’s certainly something to the way I focused on the story of Pannychis. I wrote some poems at the time: “Has Giton, Pannychis, gone from your bed, / Your Giton the color of gingerbread?” [Laughs]

Eva Ionesco, photo booth, Paris, 1978

Eva Ionesco, photo booth, Paris, 1978

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you remember receiving any other literary shocks?

SIMON LIBERATI — The second aesthetic shock, which occurred during exactly the same period, or right afterward, was the 1977 reissue, by Régine Deforges, of Kenneth Anger’s book Hollywood Babylon. I bought it at the Fnac in Montparnasse. Régine Deforges reissued a facsimile of Pauvert’s first edition. It’s the little rectangular volume you can still find used copies of now. It’s wonderful. I was 17 at the time, and it was an important year in every way. I don’t know why, but a sort of nebula began to form.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What does Hollywood Babylone mean to you?

SIMON LIBERATI — That book is at the root of many things. A whole series of coincidences that led to my most recent novel, Eva. In fact, when I first met Eva Ionesco, I told her about it, and she had the exact same edition as I did! And then there’s that buxom blonde on the cover… At the time I didn’t even know who Jayne Mansfield was. That bleached-blonde hair against the black background, and those two words, HOLLYWOOD BABYLONE, running down the sides like two pink columns. I had a shock, a real shock, a strong one, and even back then I started writing poems about Jayne. And, as you know, I ended up writing Jayne Mansfield 1967. For me, then, there’s a pretty strong continuity, but it ran pretty much underground for 25 or 30 years. It was my meeting with Eva, my love for her, and the book that I’ve just finished writing about her that tied everything together, crystallized things.

OLIVIER ZAHM — A nebula of fairly dark obsessions that corresponds to your twisted view of glamour.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes. For me, at least, it was glamour. Glamour is dying young, becoming a fat has-been, and getting strung out on drugs. In 1977, at least, that was glamour: Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen, of course. And then the extreme blondness of Blondie. Or a photo of Johnny Rotten, with his discolored hair and leather jacket, which I came across in the French news magazine Le Nouvel Observateur. I quickly steeped myself in that nebula, which fit right in with my sensibility. You know it as well as I do, but at the time we didn’t have the same level of information we have now. Things like that would remain confidential.

Hollywood Babylone by Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 1959, collection Simon Liberati

Hollywood Babylone by Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 1959, collection Simon Liberati

OLIVIER ZAHM — Were you punk in 1977?

SIMON LIBERATI — Not personally, no. At the time, in 1976, I had just stopped serving as an altar boy at the church of Saint Sulpice. Saint-Germain-des-Prés was still pretty happening. The Café de Flore was going pretty strong. It’d become very homosexual, but with lots of prostitution.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The Drugstore, with its Johns.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, its famous johns. I met a boy who looked like a small David Bowie, a very pretty boy who used to turn tricks right at the Drugstore. There were streetwalkers everywhere, girls and boys alike. There have always been female prostitutes at the Flore. There was one called Edwigette. She’d taken her name from my friend Edwige, who used to work Le Palace, and Edwige hated her for it! Later she took the name Lolita. I couldn’t figure how you could go from Edwigette to Lolita. From what I hear, she ended up getting stabbed.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How very charming!

SIMON LIBERATI — So there you go. At any rate, it was all grist for the mill. And that is the wellspring of my obsessions, albeit a fairly unconscious one. A nebula that feeds on chance, accidents, and encounters.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s as if you’d let the punk and nihilist epoch come to you because your obsessions and the themes you develop have now come to form the Bataillean underbelly of our current times…

SIMON LIBERATI — You’re right to invoke Bataille because he’s essential. Yes, I’ve read Bataille, and I’ve enjoyed his novels and essays. When I was 19, I asked for and received from my grandmother the Gallimard edition of his complete works. That’s how I learned of the existence of Thadée Klossowski. I always wondered what on earth he was doing in there, and I later understood that he’d worked on the Bataille archives at Gallimard. Since I was seeing his photos in the magazine Façade at the same time, I could never make the connection between the two. [Laughs]

Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 1979

Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 1979

OLIVIER ZAHM — What of Bataille did you read?

SIMON LIBERATI — My Mother, of course!

OLIVIER ZAHM — We should mention as well that your father was something of a poet.

SIMON LIBERATI — I was lucky enough to have parents who took the time to read aloud to me. They read me all of War and Peace, for instance. And Dickens. We didn’t have a television set, so my father would read me books. I also read a lot myself when I was young, but it was at 17, 18, 19 that I really started reading. Literature is something that’s always been on my mind, but I didn’t particularly want to be a writer.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you get to literature through your father or your mother?

SIMON LIBERATI — Through both. Well, mostly through my father, of course, because he’d been in the Surrealist group and was a poet. He’d always been one, and still is. He hasn’t published much in the reviews. He was close to Benjamin Péret. So he’d been a part of that, but it was before I was born. Let’s say that I did have what we’ll call a tutelary figure in my life, but also mention that he forbade me to write novels, because for the Surrealists the novel…

OLIVIER ZAHM — They thought it was too bourgeois. For them, it represented the end of literature.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, precisely. [Laughs]

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your father must be pleased that you’ve become a novelist after your detour through journalism.

SIMON LIBERATI — When, at 40 years of age, I told him that I’d written a novel, he said to me: “You’re not going to become a novelist, are you?” [Laughs] He could live with the journalism, but novel writing? That was a step down for him.

Eva Ionesco and Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 2014

Eva Ionesco and Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 2014

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you discover Sade in your father’s Surrealist library?

SIMON LIBERATI — Not at all. By that time my father didn’t own any Surrealists books. He’d become a Catholic. It was Bataille who led me to Sade. I read the works of Sade at the lovely house in Normandy of Cartier-Bresson’s sister, who was a charming lady. That’s where I used to spend my holidays as a child. I read Sade, whose works had been published by Pauvert, in a small, square collection. I recall a preface to Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue, written by one Georges Bataille.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was there any other childhood influence, outside the world of books?

SIMON LIBERATI — The world of the circus, most assuredly. Back then there were two circuses in Paris: the Cirque Medrano and the Cirque d’Hiver. The female trainers — I was fascinated by a friend of my mother’s, a lion tamer who later tamed tigers as well. I was also fascinated by the female Italian equilibrists, the girls who performed on the flying trapeze. And all the little girls, all the members of those circus families, even the girls who were still children.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Always that fascination with little girls.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, absolutely. The circus was wonderful, full of girls dressed in colorful leotards. There’s this little low wall at the circus, the ring, and at its center is a floor of sand, like an arena. And there were the little girls. I’d watch them, and they seemed so inaccessible. For me, they were artists, already flying through the air, dancing on horses.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You were the same age.

SIMON LIBERATI — They were the same age as I was. And I’d meet them afterward; we’d often go backstage to see the artists because my mother was friends with the ex-dancer animal trainer. [Laughs] She was a Swiss-German called Catherine Blanckaert — Blankart on the posters — and the daughter of a Swiss banker. For a long time, I had her poster up in my childhood bedroom. She was wearing Paco Rabanne and sitting on a tiger. But I’ve lost the poster. She’d been trained by old Joseph Bouglione. I think she died of liver cancer, the poor thing. Maybe not. In any case, they were all drunk at the circus. They drank like fish.

Eva Ionesco and Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 2014

Eva Ionesco and Simon Liberati, photo booth, Paris, 2014

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why wait to become a grown man before writing?

SIMON LIBERATI — I’m not sure I had any desire to write. Really, even if I did like books. I didn’t want to be a writer. I didn’t like the idea. And the publishing world held no attraction for me. I knew I had something to impart, something to tell, but I wasn’t sure how to go about it. I almost went to film school. I did some painting. I think the first time you and I met, I was still painting. I still hadn’t found my way.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Not having found your artistic road, you joined the press corps.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, but late in life: at the age of 32. I wrote for a magazine for young women [laughs], called 20 Ans, and then for Cosmopolitan. At the time I was able to write amusing things and nasty things, and that’s it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The 1980s and even the early ’90s were a period when there wasn’t yet that obsession with success and with the rapid achievement of professional or artistic or writerly status. You could dawdle; you could take your time about it.

SIMON LIBERATI — I don’t agree. I think there was already a pretty strong sense of urgency at the time. It’s just that, well, I didn’t know what to do. I’m pretty slow by nature, too — even if my obsessions are very particular and very much set.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your writing has, let’s say, something to do with transgression.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, with transgression. Yes, that’s one way to put it. Surely.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You don’t wish to theorize about it.

SIMON LIBERATI — I theorize very little, as a rule. Nor do I go in much for eroticism because my books aren’t so much “sex” books. I don’t really deal with that directly. In L’Hyper Justine, for example, it’s mostly the title that’s sexual. I read a lot of Sade when I was a kid, at 13. I hadn’t told you that! [Laughs] I couldn’t help but be influenced. I also had a Catholic education, which we know helps establish that kind of world: the arenas, Nero, Suetonius, young martyrs fed to the lions — all that stuff. Yes, all that falls within my tastes.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What’s your relationship with women? Do you know how to talk about them?

SIMON LIBERATI — Do I know how to talk about them? I think so. I think I’ve spoken a lot about them. My male characters are always milquetoasts. And my female characters are often victims, but they have, shall we say, more refined sensibilities. It’s a difficult question.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You had been working as a writer and editor for young women’s magazines.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, I’ve worked for several women’s magazines. I was an editor and advised the editorial staff at 20 Ans. I’ve even been editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan, along with Anne Chabrol, who shared those weighty duties with me. And that’s a monument of women’s journalism, a bit women’s lib — in the 1970s American sense, that is. I wrote many, many beauty pages, for example [laughs] — things like that. In sum, I think I’ve done a substantial bit of work in the women’s arena.

Eva Ionesco at Le Privilège, Paris, 1981, photo Roxanne Lowit

Eva Ionesco at Le Privilège, Paris, 1981, photo Roxanne Lowit

OLIVIER ZAHM — That’s interesting. You’re unable to generalize about women, but you can write in their name.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, I often wrote under female pseudonyms in the magazines, and, yes, I can write for women. Some of my best readers have been women, and it’s often the case today. The critics who’ve taken an interest in my work — who’ve approached it in a subtler way — have often been women. They’ve not always taken to it kindly, but they have certainly brought their attention to bear.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you were interested in fashion, especially in the ’90s.

SIMON LIBERATI — Especially in fashion shows and collections. They inspired me much more. I often used to say that I preferred the fashion world I was frequenting to the literary or cinematic world. There was power in the fashion shows, physical force, if only in the bustle of the photographers and the energy and speed of the shows. I find there’s a kind of bravura to it, a leap into the void, something I’ve always liked. Something that reminds me of the circus of my childhood. And then there are all those young women on the catwalk.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s power in fashion, but also much weakness and falsehood, and smokescreens.

SIMON LIBERATI — Force alloyed with a certain weakness. I think in some measure the people are actually pretty defenseless, too. I mean that they’re not often intellectuals, like in the art world. I tried to be an artist in the ’80s, but it was complicated for me because there were a lot of concepts and theories around art, and that just wasn’t my world at all.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Art in the ’90s was very theoretical.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes. It wasn’t my tradition. They couldn’t care less about what I knew, and I couldn’t care less about what they knew.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What pushed you to start to write a novel at 40?

SIMON LIBERATI — It didn’t happen for me until I read two French writers: Michel Houellebecq and especially Jean-Jacques Schuhl. But until then, it wasn’t on my mind because I’d see the writers of my generation and couldn’t imagine wanting that.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did Michel Houellebecq serve as an example of a writer who could find a style to fit the times?

SIMON LIBERATI — Yeah. His first book, Extension du Domaine de la Lutte [Whatever is the title in English], made me want to write. When I read it, I said to myself, “Well, what do you know; there are possibilities!” He attests to something I can understand, for once. There’s something to the blackness, something I very much liked. But I didn’t like it entirely, and the subsequent novels I’ve liked less. But that one I liked. There’s some disorder and abandon in that novel, and there’s power.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What about the cult French author Jean-Jacques Schuhl? How did you come across his novel?

SIMON LIBERATI — Ah yes, it was through his book about his wife called Ingrid Caven. I happened to find it by accident one day on the table of a journalist who reported on culture for a magazine I was working at. I pilfered it because, I mean, Ingrid Caven, wife of Fassbinder and singer, of course I knew who she was. I read the book in a few days, which for me is rare; it’s happened four times in the past 10 years.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you read his famous book Rose Poussière?

SIMON LIBERATI — I always laugh with Jean-Jacques when I tell him I haven’t read Rose Poussière. “Continue!” he says, laughing. It’s no doubt a book that’s influenced me indirectly through people around me who actually have read it. We became friends after I interviewed him for a magazine. I don’t have many writer friends. We talk shop and read each other’s stuff, and he’s otherwise just a great guy to be around. And since he wasn’t much of a socialite either…

OLIVIER ZAHM — You never wanted to meet, say, Cioran?

SIMON LIBERATI — No. [Laughs] I don’t care for aphorisms. I know he used to go to the same bookstore as me, but I never met him. I haven’t read him much either.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Or Philippe Sollers?

SIMON LIBERATI — Sollers, yes. I like Sollers. I offered Sollers the manuscript for Anthology of Apparitions, but at the time he wasn’t interested. Later, however, he sent me a very nice note about 113 Études Romantiques because in it I speak well of Breton. I don’t know him, but I enjoyed Tel Quel … and the Sollers of éditions du Seuil, with novels like The Park and Nombres.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Perhaps you’re more of a romantic. Baudelaire used to say, in essence, that the beautiful always contains some measure of unintentional, unconscious weirdness. You’ve published a book titled 113 Études Romantiques, so today you have no qualms about declaring yourself a romantic.

SIMON LIBERATI — Ah, well, that’s true because I like the word. For one thing, there’s something trite about it. And then it evokes the new romantics — you know, like Gonzague Saint-Bris. [Laughs] I, at least, don’t lay claim to any weirdness, but I’ve always been attracted to all that stuff. For me, what’s beautiful is, of course, monsters. I had a timid attraction to monsters. Eva, for instance, is a feminine monster. A monster that I love.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That brings us to your new novel, Eva, which tells the story of that figure of the Paris night, and that scandalous child who modeled for her mother, the photographer Irina Ionesco, in the 1970s. A woman you’ve fallen in love with and recently married, before writing this book about her, a book that serves as a sort of Ariadne’s thread for all your obsessions. I’ve got to ask you to tell the story because, after all, it’s pretty incredible. I imagine you’ll be telling it several times during the promotional tour.

SIMON LIBERATI — [Laughs] Thanks. The tour continues tomorrow, with Vogue.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I’ve got the scoop.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, you get the first telling. We’ll have to work out the kinks as we go.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The story with Eva is that you first met her at night in the ’80s, outside of Les Bains Douches.

SIMON LIBERATI — I met Eva a very long time ago, in the ’80s, but I’d forgotten about this first meeting.

I had no memory of it. When you went out at night back then, to Le Palace or Les Bains, you couldn’t help but be aware of this

scandalous blonde adolescent who was nuts and strung out on drugs. But I didn’t know her personally. I knew people who

knew her well. I knew Edwige well, and Edwige knew her well. I used Eva as an inspiration for one character in my first novel.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you go out with Edwige?

SIMON LIBERATI — I went out with Edwige, yeah. We were together for two months, a month and a half, two months, from December 1979 to January 1980. I was madly in love with her. In fact, I open the novel with Edwige and close it with her as well. What I discovered in writing it — among many other coincidences — is that Eva, too, had been in love with Edwige. Both of us kept love notes from her, written six months apart. We both loved the same girl without knowing each other.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That doesn’t happen anymore. Nowadays, you’d share text messages.

SIMON LIBERATI — Right, absolutely. It’s too bad because love notes, the letters and scraps of paper one keeps, are very useful for writers … Eva gave me access to all her souvenirs. I rummaged through her boxes and found some wonderful things, like a letter to Alain Pacadis she wrote when she’d been arrested in New York, at age 12, for heroin trafficking.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Any other surprises?

SIMON LIBERATI — Among Eva’s souvenirs, I also found the heroine of my first book [Anthology of Apparitions], whose name is Marina. A breakup letter to Marina. “What is this?” I wondered. It turned out to be a girl who’d fallen in love with her at the DDASS [the former French regional office of health and social services], at the reformatory. I later spoke about this with Christian Louboutin, who was part of their gang. He said, “Ah, of course! Marina was a girl who was with Eva, and who’d killed her father with a hammer.” [Laughs]

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you remember that you’d come across Eva in the ’80s?

SIMON LIBERATI — I didn’t come across her again for 35 years! The last time had been in 1979. I ended up being in the same car with her, going from one club to another. She yelled at us because the car ran out of gas and she asked for us to pay for it. I left the car. And I wasn’t itching to talk to her, since I didn’t know whether she’d read Anthology. It’s a work of imagination, but I took some inspiration from the people I’d crossed paths with at the time, mixing the facts of December 1979 or January 1980 with fiction. The most powerful inspiration was not Eva but a girl in the German book Christiane F.: Autobiography of a Girl of the Streets and Heroin Addict, a book I’d stumbled across one day loitering at an Emmaüs shop. It links up with Pannychis; it links up with The Satyricon; it links up with everything. And I said to myself, “I’m going to write something about 12-year-old girls who prostitute themselves, and it’s going to be set at the Élysée-Matignon [a club in Paris], and it’s going to end badly.” There you have it in a nutshell. I said, “I want to tell the story of Eva’s gang back then, tell it discreetly, with no names, and without mentioning Le Palace or Les Bains Douches. The words Palace and Bains Douches will not appear in the book.”

OLIVIER ZAHM — But why were you afraid to encounter Eva again?

SIMON LIBERATI — Because I was afraid that she would have read my first novel and discovered that I use her as an inspiration and that I re-created her gang somewhat. They’re not exactly the same, of course, but I did mix in some real names for kicks, and I invented “la petite Eva,” even if little Eva isn’t the book’s most important protagonist. In my book, though, she’s the worst of the lot: the biggest druggie, the most far-gone case. [Laughs] And the funeral eulogy for little Eva in the book is: “The stupid bitch overdosed.” I later learned — I’ve never been able to verify this — that Irina Ionesco, Eva’s mother, asked someone, “The inspiration for the character in that book wouldn’t be my daughter, would it?” [Laughs] So I said to myself, “Oh boy, when I meet Eva!”

OLIVIER ZAHM — She’s going to want royalties.

SIMON LIBERATI — More like: “She’s going to bust my face!” But there was none of that. Instead she tried to get me involved in writing her screenplay.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Could she perhaps not have read your book?

SIMON LIBERATI — Francis D’Orleans wanted to get her to read 113 Études Romantiques, but since she never listens to what anybody tells her, Eva went out and bought Anthology. And she recognized herself; it so resembled her life and especially her way of apprehending things. The other model for the character Marina in my novel, though, was Babsi. She was the pal, playing second fiddle to Christiane F., and died of an overdose in Berlin in ’75-’76, at age 14, whereas Christiane survived. She even had a comeback, making the cover of Stern and writing a second volume … horrible. Anyway, Eva asked me to write a screenplay with her and wasn’t upset.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And then you found yourselves falling in love.

SIMON LIBERATI — That’s how we fell in love. We fell in love because she recounted and completed the visions I had of the time. She told me things that confirmed that my imagination had fallen well short of reality. She recounted childhood memories that I’d love to have included in Anthology. It would have been fantastic. So, I put one or two of those into Eva. They form a sort of sequel or companion piece to Anthology. There’s a sort of mirror effect between the two novels, but the book’s subject — I came to a sudden realization — is disillusionment. In other words, the fascinating creatures, those little girls, those young people I used to see in the forests of my unconscious, etc., and who in the end, yadda, yadda, with the life they lead, end up destroyed.

And I suddenly run into Eva at a dinner given by the artists Pierre et Gilles. She’d put on a little weight at the time; she was a little more filled out, but still had that fascinating gaze. Eva and her son, who was like a specter of her, like her adolescent double. There’s an absolutely fascinating resemblance between the two.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was it love at first sight?

SIMON LIBERATI — I suddenly realized that the object of my fascination, the real woman, is every bit as strong as I had imagined. I have before me the person who lies at the root of my imagination, and she is not any sort of projection of mine. Moreover, she’s an artist. Her film My Little Princess is excellent.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I’m surprised that Eva let you write about her and her life, as she uses her life for her own films. And she also is fighting against her mother in court to get back the rights to the erotic, if not pornographic, photos that her mother took of her when she was still a child — scandalous photos that she’s never forgiven her mother for taking and, indeed, for clandestinely selling. She’s still got a lawsuit pending against her.

SIMON LIBERATI — It’s a long dispute between mother and daughter. I write about it in the book, so I can talk to you about it. In my view, those photos were created by two people! There’s the mother taking the shots, but also Eva, her child, a model taking full part in the creation of the images.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s like an artist couple.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, an artist couple. I’ve written so. Eva is the inspirational figure for her mother. She says this in a very interesting interview in a smut magazine of the time called Club. I saw it in the lawyer’s file. She says, “The object of my photography is really my daughter.” It’s a dark fascination, to be sure. And I think Eva has within her the thing that Nabokov defined very well in Lolita: true nymphal power. A nymphal power that she still possesses, that’s still alive…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Nymphal power in what sense?

SIMON LIBERATI — In the sense of an object of fascination, of inspiration, and of artistic direction.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In the photos.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes, because it was she who applied her own make-up, selected her own clothes and her own poses. But not everything came from her, of course.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In any case, there are no good photos without the model’s participation.

SIMON LIBERATI — Surely not. You know it better than I. The fact remains, though, that what inspired me wasn’t so much Irina’s erotic photographs, which don’t fit in at all with my aesthetic. Let’s just say I was suddenly face to face with the scintillation of a nymph, and the book carries that sheen within it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It sheds light on the encounter between your writing and a girl-become-woman with whom you fall madly in love.

SIMON LIBERATI — The object of my fascination. The primary object of my fascination.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But that leads you into a real love affair.

SIMON LIBERATI — Not only do I fall in love, I find I’ve squared the circle. I’ve come to understand what lies at the heart of my inspiration and writing. In other words, I have before me, if you will, a monster, an object that has not only been fetishized in photographs by her mother, but also been fetishized by others before me. And it turns out she is utterly aware of her power. This is linked to her narcissism, which is constantly feeding itself in the mirror… I talk about this a lot in the book.

OLIVIER ZAHM — She has control over the effect. She makes herself into her artistic object?

SIMON LIBERATI — For me, Eva is at once the object of my fascination and a true artist, with whom I can carry on a conversation as a peer. Because Eva has an artistic vision of herself and of her narcissism. It’s what has allowed her to survive because she could have died 20 times over by now.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And this is what has led you to write the story of your love for her, rather than a biography of Eva Ionesco?

SIMON LIBERATI — It’s not a biography in the sense that I recount her life. I do not recount Eva’s life. She will recount her life herself in a book. In fact, she’s in the middle of writing it right now. It’s something that belongs properly to her, and that only she herself can really recount. Me, all I do is evoke it. Also, there was already a book called Eva, Éloge de ma Fille, a photography book. My book is the second panygeric! [Laughs]

OLIVIER ZAHM — This is the first time you, or your writing, have come up against your own existence, or your imagination has been faced with the reality of your life.

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes. She’s simplified my writing as well. I had been focused on detail, on somewhat fetishistic narration, if you will. Whereas Eva is very direct. I’ve been influenced by her. I’m in greater accord with myself. I write with greater frankness, let’s say — with perhaps fewer circumvolutions. It hasn’t been easy, of course. You’ll read the book. It wasn’t easy to get to that point, not at all.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But I’m surprised to hear you say that it’s easy to write about someone you live with and love. In your previous book, love appears as rather problematic.

SIMON LIBERATI — Not in 113 Études de Littérature Romantique. That, perhaps, is the book where I started writing about love. And then, in Jayne Mansfield 1967, the love I had for Jayne is extremely evident. I think, too, that that’s what gave the book its…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Beauty?

SIMON LIBERATI — Its quality. I don’t know, but in any case, let’s say it didn’t seem too morbid a story, or too…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Were you in love with Jayne Mansfield when you wrote the book about her accidental death?

SIMON LIBERATI — When I wrote Jayne, I had a sense that I was really working with her. I knew by heart everything that had ever been written about her. I knew everything she’d said. All the quotations in the book are verbatim. They’re things she actually said, practically. I was living with Jayne Mansfield [laughs], if you will. In one of the rare interviews Eva did when she was 12, she professes her love for Jayne Mansfield. When I read that in the newspaper in question — I was myself 18, in 1978 — I said to myself, “Look at that! There’s someone else!”

OLIVIER ZAHM — In sum, then, you and Eva share a love for two women: Jayne Mansfield and also Edwige…

SIMON LIBERATI — [Laughs] Yes.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Are you happy with this new novel Eva?

SIMON LIBERATI — Yes. I’m pretty proud to have brought some order to the chaos. It holds up. It holds up well. Ha, ha, ha. It’s certainly my best book!

OLIVIER ZAHM — It grabs you.

SIMON LIBERATI — Oh, yes. It holds up, and it’s got claws. You’ll see. The book’s very realist, too, when things get very specific. I’m very happy with it, indisputably so.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And on the heels of that book, you’ve embarked on another story, but a bloody one: the three days of Sharon Tate’s murder by the Manson family.

SIMON LIBERATI — That came earlier, actually. You see, I live on credit, off publishing contracts that I sign before having written the books. I signed a contract for the murder of Sharon before I wrote Eva. So there’s a big contract with the publishing company Grasset for Sharon that I have to honor. It’s a book I’ve been dragging behind me for months, for years and years, to the point where I’ve amassed documentation, pored over statements, and so on. It’s become a nightmare.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But isn’t the Manson family rather hackneyed and clichéd as a subject?

SIMON LIBERATI — No. It’s fascinating. Critics might find it hackneyed; I have no control over that. But the story itself is in every way very interesting because I’ve really entered into the individuality of every member of the clan. It’s a blood crime recounted by four people, the four killers. I began with their testimony and the books they’ve written. They’ve all written memoirs.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Is it an inquiry or a crime novel?

SIMON LIBERATI — It’s a novel. Nothing to do with an inquiry. I recount the murder through the voices of all the characters, and in detail. In other words, I use all the material, as I did for Jayne, but perhaps to an even greater extent. I use everything that’s been said about the crime. Everything in the book is 90% to 95% authentic. But the narration is not the kind of narration you’d find in a book that digs into the Sharon Tate case. That’s not what it is. It’s fiction.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So what’s the overall result?

SIMON LIBERATI — A somewhat gory sort of literary teenage movie. It was an amateur crime. They had a lot of trouble killing people. It was a slippery, squealing, hollering business! In fact, it’s the phenomenology of a 20-minute blood crime. I supply an account of those 20 minutes, and then the aftermath of the crimes, and the second series of crimes. So we spend two uninterrupted nights with them. But it’s not a hate-filled book. It doesn’t pulsate with darkness. It’s more of a book about youth.

END