Purple Magazine

— F/W 2015 issue 24

Hélène Cixous

Hélène Cixous in her apartment in Paris, photographed by Olivier Zahm

Hélène Cixous in her apartment in Paris, photographed by Olivier Zahm

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM and DONATIEN GRAU

Hélène Cixous (born 1937, in Oran, Algeria) is a legend in contemporary thought who has played a crucial role in shaping today’s feminism. With the concept of écriture féminine (feminine writing), she encouraged women to explore the many possibilities of their sexual identity; she has made it the source not of limitations but of freedom. Her work as a writer places her among the most innovative voices of contemporary literature. Here, she tells us her personal history, and discusses what it has taken her to become who she is.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I’d like to start with your birth in Oran, in French Algeria. What was your childhood like?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I am a mass of continents, contradictions, compatible incompatibilities. I was born in Algeria and am the result of the history of the world at a very specific era, an era rife with violence, revolt, promise, hope, and despair. I was born in 1937. My mother, a German Jew, left Germany in 1933. As soon as Hitler came to power, she understood it was necessary to leave. My story begins before I was born, with the Jonas, Klein, and Cixous families, which already had a long history of cultural and political adventure. My mother’s family, for instance, encompasses the totality of European history. My maternal grandmother, Rosalie Jonas, is of a family from Osnabrück, a small town in Hannover where the Jews were closely associated with the future of Germany. My grandmother, born in 1882, read poems before the kaiser when she was a little girl. Thus, when I was a little girl of the same age, it was a part of my “memory” that my grandmother had recited poetry for the kaiser. Those Jewish families lived in a world where, for a while, it seemed possible for the Jews to reach a sort of moment of stability. Abraham Jonas, my grandmother’s father, was president of the Jewish community of Osnabrück, of which nothing more remains. They were all deported, except those who managed to leave in time. My mother later re-established good relations with the city and City Hall. Osnabrück indeed has undertaken thorough and honorable memory work, like other German cities. In Osnabrück there are stolpersteine monuments dedicated to members of my mother’s family. My grandfather, Michael Klein, was from an Austro-Hungarian family. He was born in Trnava, in a small city between Bratislava and Prague. Back then it was Austria-Hungary. In the early 20th century, the Austro Hungarian and German empires both maintained a policy of reducing the violence directed at Jews. The Austro-Hungarian Empire abruptly made it legal for Jews to hold land. As the history of anti-Semitism reminds us, Jews were barred from holding land. Then, suddenly, they had the right, and my grandfather’s family acquired some: they had an enormous farm. Michael Klein, my grandfather, was the 10th of 20 children. As his father had devoted his life to studying the Talmud, it was his mother who rode around the property on horseback to run the farm. My grandfather traveled all around Europe, as it was easy to do at the time. The Jews were great travelers. They crisscrossed Europe from community to community, conducting their business. Upon reaching German Strasbourg, my grandfather built a factory for packing materials that still stands today. Seeking a wife, he came to Osnabrück and asked for the hand of my grandmother. The Jonas family replied: “All right, then. We shall give you our youngest daughter. But you are Austro-Hungarian; you must become a German.” So my grandfather became a German. Soon thereafter, the rumblings of the First World War began, and my grandfather said to himself that the Jews must become Germany’s foremost patriots.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Patriots.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — It was a common idea at the time. On the one hand, there was a very strong current of Zionist thought or ideology and, on the other, a sort of idealist nationalism. In 1914, although already 34 years of age, Michael Klein joined the army. He was not supposed to see combat, as he had two children. He was killed two years later in Belorussia. It earned him Germany’s Iron Cross. Thus, my grandmother, who lived in Germany — in Strasbourg, that is — became a war widow, with two little girls in her charge. She went right back to Osnabrück; my mother had a German childhood and a German education. This story had a mobile setting and crossed little patches of Europe with the vagaries of the war. My mother, born in 1910, arrived at Osnabrück in 1918 and was raised in Germany. Hitler came to power; my mother left. She was 19 and went to England to learn English, then to France to learn French. In Osnabrück, Jews had now been banned from the swimming pool. My mother said to her sister, three years her junior: “Come to the pool in Paris!” My aunt followed my mother, who was always quick to grasp the political situation, though never trained for anything of the sort. My mother always said that her country was Europe. As a young woman, she was already rejecting any kind of nationalism. It was to be banished, and Europe set up in its place.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And your father?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — His family was from Spain. There are administrative records that go back to the French colonization; the family then followed French colonization in Northern Africa. My father’s ancestor, from Gibraltar, crossed the strait and followed France’s conquests into Morocco, Algeria, etc. My paternal grandmother and grandfather were born at the border of Morocco, and followed the French path to settlement. In 1867 — before the Crémieux Decree, when Napoléon III, who was much less colonialist than the French Republic, offered French citizenship to Algerians, generally referred to as Arabs, as well as to Jews — my family took French citizenship. The dream of France took shape in the possession of the complete works of Victor Hugo. Samuel Cixous, my grandfather, never had time to read him, having worked since the age of 11. He opened a shop in Oran, a city very Spanish in character. My grandfather dreamed of France and said that France is the future for the Jews — something my mother would never have considered. He opened a shop on the Place d’Armes, Orans’s central square. It was both a hat shop and a bazaar selling binding, French-navy berets, postcards. He called it Les Deux Mondes. It was on a corner of the square. The “two worlds” of the name, could they have been Africa and Europe? It was a very theatrical square. Across the way stands City Hall, built by the Europeans, and in front of City Hall were two enormous lions. The last lions of Algeria. I was fascinated with them when I was a little girl. They were the last; there were no more lions. The French army had killed off Algeria’s lions. My grandfather must have had a vision of the meeting of two worlds. Lion and man? There were a great many “two worlds” in my childhood. On my mother’s side, there were the two empires. All I know is that the world is more than one world. I have known since I first started walking that the world is at least two worlds. There were two worlds plus two worlds plus two worlds. It was a universe of conjunction and disjunction: on one side, there were worlds that met, as in the extraordinary meeting of my mother’s and my father’s respective worlds. That was a no-no: the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews were not to meet, not to mix. The Jews of North Africa, of Hispano Arabic origin, didn’t even know other Jews existed. The Ashkenazi were horrified when they saw Sephardim. The Ashkenazi passed for aristocrats. I learned both of the plurality of these universes and of the racism, the vermin infecting all humanity. Prejudice ran very high in Algeria. It was a country founded on racism. There was colonialist racism, the dominant form, which was virulently anti-Arab: The “Arabs” were of course to be seen as inferior peoples, afflicted with every vice, with every shortcoming, with every weakness. There was the racism of Arabs toward Jews, and vice-versa. I was protected by the Enlightenment because my family was miraculously driven by a sense of humanity. They were sensible people, well aware of the horror, of the plague, of the various types of racism. Through memory, experience, and a spirit of justice.

A drawing by Adel Abdessemed

A drawing by Adel Abdessemed

DONATIEN GRAU — Your mother played a very important role in your childhood.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — She was a polyglot. Her meeting with my father: that is the history of colonization. My grandfather Samuel Cixous was a traditional man. He had two daughters and two sons. He arranged for his sons to go to university and withdrew his daughters from school. Reading and writing was enough. To their dying day, my aunts deplored that injustice with tears. Those lovely, intelligent women were deprived of an education by their own father. But my father became a doctor. He entered the French university and became subject to the colonial organization. You would start but not finish your studies in Algeria. You would earn your agrégation [the French professorship degree] in France. If you studied medicine in Algiers, you had to defend your thesis in Paris. So every mature brain was sent off to France and subsumed by the French establishment. Algeria was being decapitated. My father went to Paris to defend his thesis in 1935. There he met my mother, through a friend, at a family pension. She had veered off the European path, and my father off the African path. When Omi, my German grandmother, found out that her daughter was going to North Africa, she thought she was going to marry a monkey, a Jew with a tail. Omi remained in Germany until late 1938. By then, at the height of Hitlerism, there was no getting out of Germany anymore. Except that my grandmother received a letter from the French consul in Dresden, informing her that she had a French passport, which she didn’t know. All the old Alsatians had dual citizenship. My grandmother needed only make the request to get a French passport. At the end of 1938, she joined us in Algeria. These were huge families. There were at least eight children on my grandmother’s side and even more on my grandfather’s. On the Klein side, they were for the most part deported. They’d been farther east, in Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania. On the Jonas side — my grandmother’s side — I’d say 50 percent of the family was deported. Especially the elders. The younger members arranged to leave. Those who couldn’t go into exile ended up in camps like Gurs and then were sent on to other concentration camps. Others left for Anglo-Saxon countries — the United States, England, South Africa, Australia — and still others for Argentina, Chili, Uruguay… My mother’s family was scattered halfway around the world.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your own history lies at the crossroads of all of European history, of colonialism.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — In 1939, my father was mobilized. He was a physician-lieutenant, stationed on the front in Tunisia. He had a small problem, signs of pulmonary trouble… In 1940 he was demobilized and stripped of his French citizenship. In a single stroke, with the anti-Jew laws, we who had been French much longer than most of the French in Algeria or in France lost our French citizenship. My father was forbidden to practice medicine: professions were forbidden us in North Africa, as they were in France. Under the anti-Jew laws, the sole difference between what happened to us and what happened to the Jews in France was that we were “liberated” first because the Americans landed in Algeria in 1942. I didn’t go to school; it was forbidden. My father was no longer practicing medicine. That’s when my mother started working. She was a cutter and seamstress. Later, when the Americans came, the Jews did not have their rights immediately restored. My mother instantly took up with the Americans, doing secretarial work. The first square meal I had was when the Americans came. We suddenly had tins of butter, white bread, jam. I fell in love with the jam-bearing, loud-laughing Americans, like all the people liberated by them. We were raised on Roosevelt. I cried when he died. It was terrible. It felt as if we were losing a kindly person. We followed politics. My father was an atheist and a socialist. His close friends took up with De Gaulle. The word “Allies” was warm and sweet.

OLIVIER ZAHM — We go from the army to statelessness.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — That was a wound from which my father never recovered. He had been a socialist in the time of Blum, an idealist. That was when he lost his faith in the French Republic. After the war, he started practicing medicine again, left Oran, and moved to Algiers, where he opened Algeria’s first radiology practice, ordering in the equipment from England. He died in February 1948. My mother found herself alone in a city she didn’t know, penniless, with no family or friends around. She toiled like mad to support us, first as a secretary, then seeking out a profession. She undertook to become a midwife. I was 14 and studied along with her. She was 40 at the time.

DONATIEN GRAU — And thus you made your first approach to literature and poetry, felt your first desire to write.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — The desire to write was a great help to me when my father died. I had already been shaped by literature as a little girl. For one thing, my father was a reader, a man of extraordinary talent. When we were young he immersed us in the French language. He had memorized the Larousse dictionary. I recall feeling a shock of delight when I was six, because he taught me the word extraordinary. It was, I thought, an extraordinary word. I was swimming in a world of languages. My mother spoke German with Omi, who spoke to me in German and French. My paternal grandmother spoke Spanish around the house. My paternal father’s family spoke Spanish. I started learning English very early on. When I was 13, my mother sent me to England. I had to go from Algiers to Marseilles, and from there by train to Paris. Then from Paris to Dieppe, and from Dieppe by boat to New Haven. And from there by train to London. In London, I was taken in by one of the formerly German families on my mother’s side; they were now English. I liked England. In 1950, London lay in ruins; it was much poorer and in much greater difficulty than France. We were given meal tickets when we arrived, for instance. I went hungry in England, whereas in France people were already well fed. So I straightaway got the story of wartime England, of England’s resistance, of a marvelous England that I loved. When I returned to Algeria, I was fluent in English. And I soon had only one thing in mind: to leave Algeria as soon as possible; it was an abominable place filled with violence, hatred, contempt for other human beings. I was sure the place would one day explode, and I eagerly awaited that day. I was completely in favor of the Algerian people. My father had worked in solidarity with clients that were referred to as “Arabs.” My mother’s clientele was also essentially “Arab.” She worked in the casbah. I knew from the time I was a little girl: this is a world of total alienation, a world of people blind to their fellow human beings. My mother had found a purpose for herself, bringing babies into the world. I recently took the register in which my mother recorded births to Karim, the Théâtre du Soleil’s cook, who was born in 1963 by my mother’s hand. It made sense for my mother to be in Algeria.

Portrait of Hélène Cixous’s mother

Portrait of Hélène Cixous’s mother

DONATIEN GRAU — Your father’s death hastened your entry into the world of writing.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — When I was little, I wanted to flee; I wanted to get out of that repugnant world. I found a solution: I would climb a tree, taking books up with me. I realized very late, when I discovered his high school notebooks, that the choice to do medicine was not at all my father’s. Unbeknownst to me, he had taken a first prize in philosophy. He was a man of letters. He had amassed a library in the Proustian manner. He was a subscriber to the Nelson library and had the whole collection. He also owned the first Gallimard editions of Proust. I was absolutely mad for books and would read them in alphabetical order. For me, they were all equal. I could vaguely sense a small difference between Dumas and Edgar Allan Poe, but my reading was scattershot. I lived, then, in the other world. The second world was literature, and I was also fortunate in that my grandmother, although she had not carried her studies very far, had a passion for German poetry. Omi would sing and recite poems to me by Goethe and Heine, and I loved it. I said to myself: “That’s the path for me.” Down the path of languages, literature, and books. I’d be a reader; I’d live in books. It was a brutal thing when my father died. It was the apocalypse; the world was gone; I couldn’t even walk; the ground had vanished beneath me. It was terrifying. I wasn’t yet 11, I was in sixth grade, and the world had gone. When my father was carried away — he’d suffered hemorrhages and died within a few days — I started writing for him. I saw him one last time, through a window. Our relations were already fairly phantasmal. Knowing he was seriously ill, my father was already keeping a certain distance between him and us. He avoided contact.

DONATIEN GRAU — Is that when you began writing in earnest?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — Right then, at that moment, is when I began living in that world. That’s where I settled. Relations with my French professors quickly soured. I was inventive. I was very daring at the time, I realize. Sometimes it was well received, sometimes not. I never hesitated over the path I ought to take. I had to live by books. I couldn’t do otherwise. It was the only thing that could tolerate me and that I could tolerate. The political world I already knew. I had seen it up close. I was good in history precisely for political reasons, because I kept track of the fate of all the peoples I knew. I was an expert in evil. I dreamed of books: we were poor, and my father had left us in dire straits. It wasn’t until much later that my mother began earning enough of a living to support us. We lived off what my father had planted in the garden. We sold the flowers, which was terribly painful for us. We walked everywhere. I was very careful with my expenses. “I must help my mother as soon as possible.” So I earned my agrégation in a flash. I was in hypokhâgne [first of two years of post-secondary study in letters] in Algeria, and I got married, partly in order to get out of there. I was 18.

DONATIEN GRAU — You speak of politics: you’ve made your literary life into a sort of political proposal.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I’ve always thought so. I knew, also, that it was a rather elitist way to go about it. There had to be books. The Algerians had no books; they didn’t go to school. Since the house my father had rented was in an Arab neighborhood, I was living in a world where there were only a handful of “Europeans.” The Europeans never ventured into those neighborhoods; they didn’t know them. Next door to us was a shantytown with 50,000 Arabs and a single fountain for water. At our gate there were “little Zarabes,” as they were called, barefoot and dressed in rags, who would ask us for bread. I was living amid misery and pain. It was frightful. Never the twain could meet, save some rare exceptions. For the little Zarabes, we were “French people” — we who were not French.

DONATIEN GRAU — Your literary and political lives don’t seem all that elitist in light of the impact that écriture féminine [women’s writing] has had.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — When I began turning my attention to women I was 22, 23 years old. I was no longer fleeing into literature. By then literature could become the most democratic of the world’s possible tools. One needed only have access to it. But I was living among a proscribed, banned people, who had no access to the tools, who were not admitted to the schools. I arrived in France in 1955. We were then entering a period of decolonization. There was the Algerian War, the so-called “events” in Algeria. I was relieved; it changed my life. I emerged from the plague, from that monstrous nightmare, and found I could develop a thirst for my own life. But I didn’t have a life of my own. Algeria had alienated me from it. Once Algeria had set about liberating itself, I found I was liberated as well. Landing in France at 18, I was greeted with a surprise: when I entered rooms or lecture halls nobody yelled out “dirty Jew,” the daily insult in Algeria. I was surprised. For that brief period, France was not anti-Semitic: there were no Jews left in France. For a few years, until 1962, the givens of anti-Semitism were attenuated. The Jews of France had been deported. French people of my generation had never seen any Jews. They were all dead. But when I went to the university, I encountered something that I had never known in Algeria: misogyny, everywhere. I was from a world that liked women. The women of my family were strong; they carried the family. And in France I suddenly realized that the world was split in two and governed by the pretentious cretins who played at being university professors. I understood then that the chief battle was going to be to deconstruct a phallocracy.

DONATIEN GRAU — And to construct femininity. A central component of your work over the years is the notion that gender is not in any way a limit but, rather, a liberty.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — Yes, of course. But for everyone: men, women, animals. As it happened, I completed my studies very quickly, in tribute to my mother. And immediately thereafter I was taken in hand by some excellent men, some exceptional men. My thesis advisor, a marvelous man, a great man of letters, and a former member of the resistance, was so removed from misogyny that he chose to take me under his wing. His name was Jean-Jacques Mayoux. I was truly fostered and respected by men of a certain age who were great doyens at the Sorbonne, and themselves members of minorities and marginalized.

DONATIEN GRAU — Was it then that you met Derrida?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I met him at the very beginning. My ex-husband was a contemporary of Derrida’s. One day, I went into the Sorbonne’s lecture hall, for me a sort of monstrous lair. I was 18 and fresh from Algeria. There was a young man in the lecture hall who was in the middle of his oral examination for the agrégation in philosophy. The young man was on the far side of the hall, with his back to me, facing the jury. I listened, fascinated. “Listen to that! He’s talking about the very stuff that matters to me, and doing it in my language, to boot!” The theme was “thought of death.” It was Derrida. I read him as soon as he was published in Critique, in 1963; once again, it was my language. At the time, I was having trouble writing my thesis on Joyce. I had earned my agrégation at 22, and I started in on that thesis. I had to fight to get a thesis on Joyce accepted because I was a woman and women were not supposed to read Joyce. When I started making progress, I was already embarked on a modernity that ruffled feathers all around me. What I was doing was seen as too modern. After a while, I got tired of coming up against old-fashioned resistance. I was 25 and had a post at the University of Bordeaux. I wrote a letter to Derrida asking whether he would agree to meet me to talk about Joyce. He replied: “I don’t know Joyce very well, but we can meet and talk about it.” That’s how it happened.

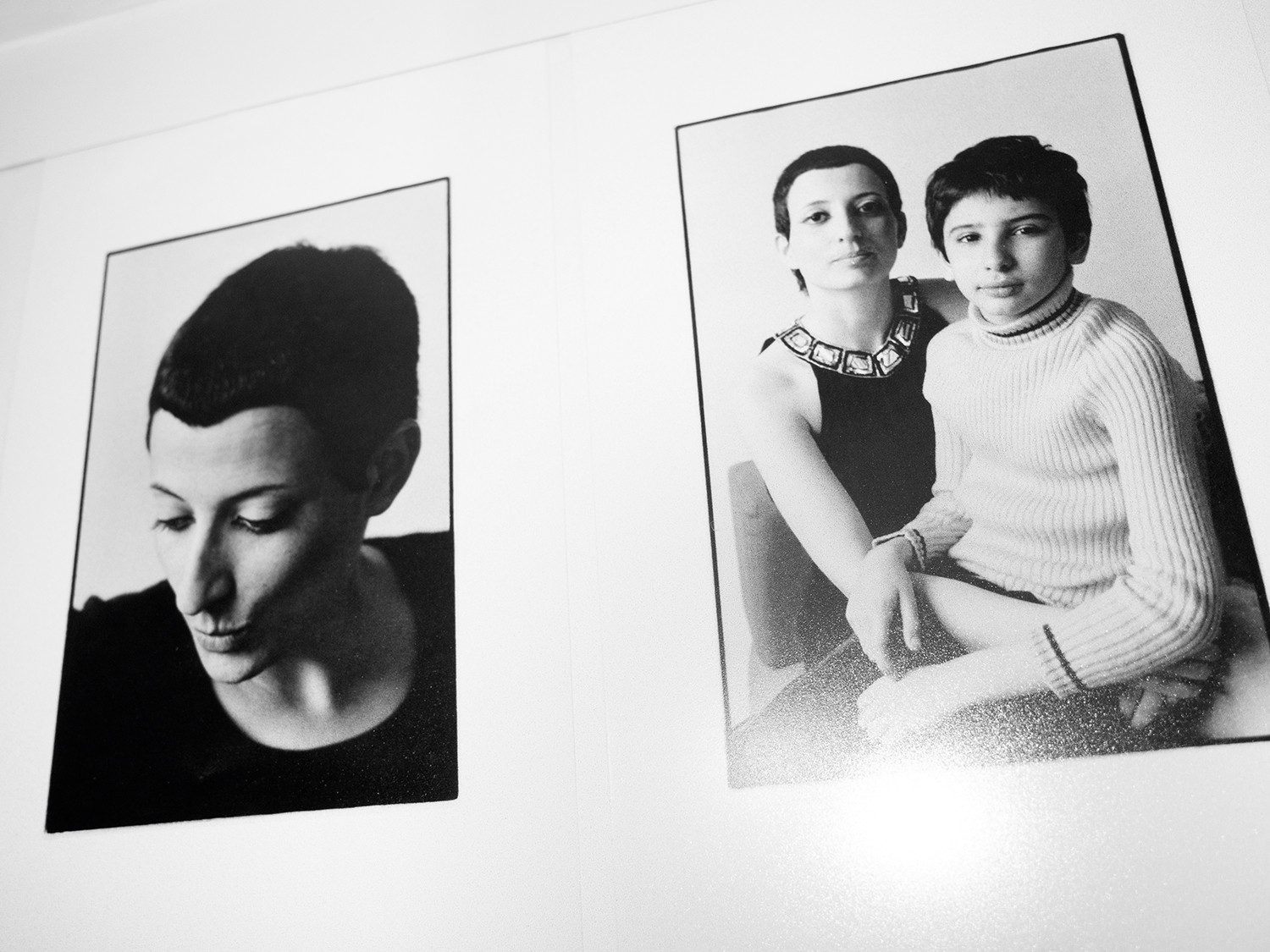

Hélène Cixous and her son

Hélène Cixous and her son

DONATIEN GRAU — It’s fascinating to see over so many years the many parallels between what he did and what you do: his deconstruction of masculinity, your deconstruction/reconstruction of femininity, the way you both write. Aside from the fact that he wrote a book about you, then another, and that you wrote a book about him, then another. It’s extraordinary to see how far the conversation has gone.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — We started out together in 1963. There was that first, long dialogue, and then we were necessary to each other, as he says in H. C. for Life, That Is to Say…: “We have no doubt never parted.” It’s a never-ending dialogue.

DONATIEN GRAU — It’s interesting that it took until the late 1990s, early 2000s for you to undertake a collaborative work, Veils, for you to write a book about each other.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — We were going down the same path together. After 1964, we were almost always exchanging our latest writings. It’s thanks to him that my first book, Le Prénom de Dieu [God’s First Name], saw print. He wrote the preface, which has not been published and which I have here. At the last minute the publisher, which back then was Grasset, said: “It’s going to be too difficult.” From then on, “It is as if we had almost never parted.”

OLIVIER ZAHM — You exchanged ideas without worrying that the other would use them?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — The fear did exist. It was mostly he who appropriated things. So he would telephone to make sure he wasn’t lifting one of my ideas. “You haven’t said that, have you?” One morning, I was in Arcachon, at the house where I do my writing, and described for him a scene that was happening before my eyes. “Aha. I’m stealing that,” he says. “Careful! I’ve just written it myself!” I reply. He says: “It doesn’t matter. No one will notice!”

DONATIEN GRAU — If we consider what you both write — a literature that thinks, a philosophy that is literary —your work leans more toward literature and his more toward philosophy.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — It’s a topic we gave some consideration. “Do you think,” he said, “that if we were in the same field, both philosophers or both writers, we could have maintained the same harmony, the same perfect friendship?” “Yes, of course!” I replied. But he didn’t think so. Sometimes he’d say to me: “Now, this you will not take from me! Got it?” The memory-amnesia system was always bamboozling us, even though the ceaseless conjunction was more explicit with me than with him. I felt less threatened than he did. He was more prudent in his relations with the outside world, in every domain. He would take me to task for my imprudence; he’d warn that I was taking risks, or that I wasn’t pedagogical enough. We maintained a certain discretion. As he saw it, if we bared ourselves on a stage filled with all manner of hostilities — hostilities toward me, hostilities toward him — we would double our trouble. And he was right.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How so?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — We were “on the same side” in our thinking, were part of the same scene, belonged to a certain modernity, etc. I’ve worked on his texts all my life. From the beginnings of Paris-VIII, since the ‘70s, I’ve initiated generation after generation of students to the thought of Derrida. I have never had any reservations about it. But our proximity, our exchanges urged upon us a sort of reserve, a reserve that sheltered our friendship. It endured until ‘91-‘93. Then he lifted the interdiction. I figure he must have thought that the risk was minimal by then: he had established a huge worldwide reputation. So had I, in fact. He figured that we ought now to appear together. It was he who lifted the veil; it was his decision. He’d wanted to do it explicitly. He started writing books about me, laying down the legend, asserting that we “never parted, since the beginning.” It had come to be all right. But he maintained his prudence, for example, in regard to his relation with Marxism. He explained his position. For decades he had never explained himself with respect to Marx because he was faced with a whole tribe of Marxists and Althusserians who had been his students, who were “Marx-ginalizing” him. He figured that his voice would be inaudible, that in the face of that front he would be unable to convey his debt to Marx. And then, at a certain point, in 1993, he was able to make his voice heard, with Specters of Marx. The time had come.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The intellectual world to which you belonged was so vibrant and seemed like such a real adventure. One tends to think it was an exception and will never happen again: the capacity for exchange and discovery in that thought, the way it played for high stakes… Where do you see it going from there?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I see everything in terms of the future, and I’ve always seen it that way. Otherwise, I’d have long since been dead. When I got involved in the women’s movement, which I hastened to do, out of pragmatism, I thought: “We’ll never get out of this; we’re in for a 300-year wait.” Some say the battle will come to an end and, we must hope, to a resolution. The same goes for democracy: 500 years, if not 3,000. It’s like anti-Semitism and other such plagues: I have never thought that we might wipe anti Semitism from the face of the earth, or that misogyny will come to be treated as a disease and suddenly disappear. We must always think of these scenes as battles that take place at specific locations and times, that are violent, and that must be fought and won. Any victory is secured momentarily; soon the battle will move elsewhere and revive. The same thing happened with the formidable advance in thought of 1968. Just as we had a marvelous moment late in the 18th century and early in the 20th, when Europe was wonderful, the West was wonderful. We invented everything in every science. It was marvelous. Then it was over. The 20th century’s era of physics and mathematics: over. And, well, it turns out that I had the misfortune, which I consider a stroke of luck, to have spent my childhood in a monstrous world. It taught me a lot, and I don’t regret it. Later, I was a young woman in a world that seemed instead a paradise. My children have experienced it as well. Since I had children very early, they have shared in it with me. They were my companions through the happy times of the ’70s, when the gems of thought of what is called French theory spread from France to the rest of the West. When I began to write, I had Blanchot and Gracq at my side. One must try to be worthy. There were noble philosophers, dazzling linguistics, applied mathematics, psychoanalysis. After Freud, there was Lacan. A slew of luminaries and innovators: Derrida, Deleuze, Foucault… It was a happy time: those researchers were able to come together thanks to the movement of 1968. They finally met, exchanged, gathered together, and effected a worldwide change in thought. Now we are in a fallow period. It is not pleasant. I feel sorry for my grandchildren. I find they are living in an era of ashes.

DONATIEN GRAU — There are people who read your books and come away from them with their lives changed in a deep way. Many of them, moreover, come from emerging countries. How do you feel about the powerful impact of your work?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I’m grateful for the flattery. It always feels good. From time to time, I get news from the rest of the world through my seminar at the Collège International de Philosophie. At present, there are 25 nationalities represented in the seminar. Two young women talked the whole way through one session. It bothered me, and when class was over I told them so. One was a Chinese anthropologist, the other an academic from Canton. The one from Canton didn’t speak French, but English. She informed me that my work is now part of the canon at the Chinese university. She had a three-week scholarship from France. She asked whether I could go to Canton and whether they could put on one of my plays in Cantonese. She asked me questions about Freud. She was just like an American. Same level of knowledge, same way of articulating ideas. I was surprised. I’m used to having friends in Taiwan, people who’ve been totally Westernized, but when it came to mainland China, I thought of my old Chinese scholars who were still under the influence of Maoism and far from that level of subtlety. I know that my books have long been translated into Chinese, but I had no idea that they had since become standard in mainland China. As we speak, there’s a production of Portrait de Dora in Greece. My texts and characters also have stopovers in Guatemala, Uruguay, Helsinki.

DONATIEN GRAU — Without a doubt, it must be that the écriture féminine you’ve expressed has great liberating power for individuals.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — The main thing is that it’s true. There are times when that diagnosis is denied. In France, there has been a terrible backlash. And yet it’s absolutely true, and it’s perceived and lived as such, innocently and, in the end, joyfully, in most of the world’s countries, from Iceland to Korea. There’s something else that I find highly amusing: it’s young singers who are taking up my texts. There’s a singer these days, called Maria Minerva, who’s on a world tour, with my blessing. She must think I’m dead. She’s an Estonian with a lot of talent. Her first album is titled Cabaret Cixous. There are also some popular singers in the United States and Great Britain who’ve taken up my texts. The filmmaker Marc Jackson is citing me in his promotional tour. “The Laugh of the Medusa” is heralded by Taylor Swift, the country singer. A lot of artists are using my texts and finding nourishment in them.

DONATIEN GRAU — That’s something that has always fascinated me: your permeability, your ability to receive artists into yourself, invite them along with you.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I just read; that’s all. I read as Proust reads in his Journées. I can read a tree, wisteria, the relations between my cats and the pigeons, or an installation at a gallery.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It might be considered very difficult: you’ve got to find an adequate language.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — And that, perhaps, is my double world, my heritage from when I was little, when I lived as a fugitive in the most elaborate literature and when, at the same time, I was communicating with signs. I still use signs to communicate with people whose language I don’t speak. I should say, to his credit, that when I was 10, my father got me a teacher of Arabic and a teacher of Hebrew. I started learning Arabic, and then my father died. Humanity has always been able to communicate in gibberish. The poor Algerians were compelled to speak French because they were employed and exploited by the French. My father tried to turn the tables. I lost my Arabic with his death. One of my best friends, Alia Mamdouh, an Iraqi who doesn’t speak a word of French and a remarkable writer, reads me by groping her way through English translations. We’ve been speaking something-or-other for 15 years. I read her in French; she reads me by sniffing out her way through the English. When we’re together we say everything we need to say, somehow.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I saw you speak on television on the topic of euthanasia, an important subject. You’re in favor of giving people a chance to decide on their own death.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I have long sat on the committee for the Association pour le Droit de Mourir dans la Dignité [Association for the Right to Die with Dignity, or ADMD], an association that attempts to make some progress with the laws concerning what is called euthanasia. It’s always troubling for me to step into the world of the law. You’re compelled to use rigid forms and untoward words with an awful sound. The word “euthanasia” is not the word used by the association. It’s a bad-sounding word, with very ugly phonemes. There are so many philosophical questions to set out. On this subject, I err on the side of prudence.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, it’s as a philosopher and as an artist that you realize that science and medicine go too far.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — Too far? Or not far enough? I can’t say that medicine goes “too far.” It is subject to its own laws, with the Hippocratic Oath, which is both necessary and catastrophic. Doctors must swear to serve life alone. The problem being: what are we going to call life? The law cannot regulate the undecidable. Once we reach a zone where we are no longer assuredly within the realm of life, a zone where we have life without life, are we in fact still dealing with life? Here the world is divided. As we all know, society is opposed to a doctor’s intervention. Doctors are not protected, not only from legal liability for someone’s death, but also from the crushing responsibility of one day having to administer something we call death. This demands a real change in the way we think. We’d have to reach a point where they could think that what they administer and we call death is not death. It demands that we think of death as a part of life, that this death at that time is a different life. Salvation. It’s a very difficult thing to think, and the learning of it is so complex, that we mustn’t reproach doctors for their inhibition. They are in no way trained for things that are beyond us.

DONATIEN GRAU — You were speaking earlier of Derrida’s agrégation defense. That’s something that has been with you all along: feeling the life in life. This is, of course, what you did with your mother.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — For me, my mother was the very mystery of life incarnate. She was the goddess of life; she was life itself. She was a materialist who was at peace, never thinking there would be anything after life. I’d observe her. She just enjoyed life in the most extraordinary manner. She was a happy, wonderful creature. Until her life was violently stripped away from her. She was more than 102 years old. An accident, and she entered into a pure state of suffering. Death sought her out, scratched at her, wounded her, threw her to the ground, and my mother began to suffer. We’re never prepared for anything. I think that at the end of her life, my mother was deprived of death’s tenderness. I was with her, and we lost life without gaining the grace of death. I have never understood what she was made of. She loved life above all things: it was her supreme value, and she made marvels of it. I have never been unconditionally “in favor of life.” I had no desire to live at any cost, for instance. But for my mother, it was the supreme value. I’d ask whether she could go on living without me, and she’d reply that it would be terrible but she would do it. I’d tell her that that was not my plan at all. But we can’t effect conversions. My mother survived her father’s death and her husband’s. Whereas death mutilates me. With every person I’ve lost, I’ve been diminished. I’m not about to lie to myself. My mother would carry on. She’d go see the flowers, enjoy her croissant in the morning, look at it and say: “Poor little croissant.” And — gulp — no more croissant. I was absolutely enchanted with her, but she didn’t form my character.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was she proud of your success?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — No. She thought it absolutely pointless, as well as dangerous. She thought it’d be better for me to stroll through the park with her, which would have been much better for my health. She also thought all success was a threat. She was modesty itself.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Have you been subject to many attacks?

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — I’m very withdrawn as a person. I’m not on the social scene. I remain beneath my mother’s tent, very far from any sort of publicity. My mother feared vulgar attacks, jealousies, and other possessive impulses. Nothing worse than “glory,” she’d say. “Poison.” She lived in horror of glory. She considered that it was because of glory that wars were fought, and she wasn’t wrong. “Maman,” I’d tell her, “it’s not glory I’m interested in. It’s beauty. It’s language.” She’d say: “Then hop to it and exorcise that demon. Now, come outside with me.” Or: “Maybe if it earned you a little money! It’d make your life easier.” That worried her. If I’d written some bestsellers.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s not just beauty but ideas as well.

HÉLÈNE CIXOUS — But beauty is indissociable from thought. Beauty thinks and gives rise to thought.

END