Purple Magazine

— F/W 2015 issue 24

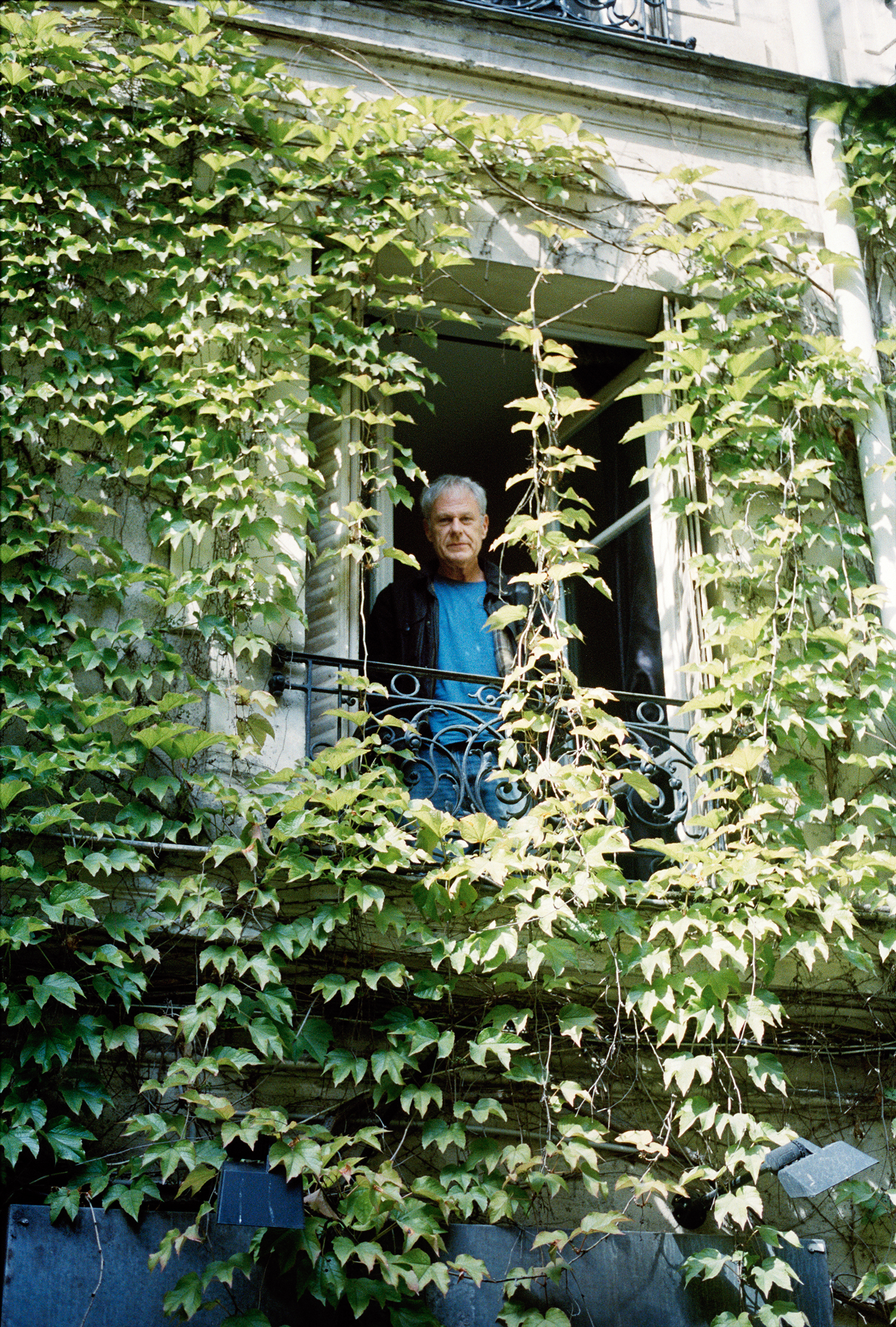

Dennis Cooper

Dennis Cooper

Dennis Cooper

on avant-garde today

american author

interview by DONATIEN GRAU

portrait by GIASCO BERTOLI

DONATIEN GRAU — You were born in Pasadena, grew up in Arcadia: how did you discover you were a writer?

DENNIS COOPER — Well, I didn’t really write until I was about 12 or 13, I think. But I had this grandmother, my mother’s mother, and she was kind of amazing. She maybe would have been an artist in different circumstances — she was very creative. She would always tell these really crazy stories to us as kids, and I remember being very taken with those.

DONATIEN GRAU — What were the stories?

DENNIS COOPER — She was really into Winnie the Pooh, so we were like bears. But then I just read junk. I didn’t really care. When I was a kid, I read The Hardy Boys and…