Purple Magazine

— Purple 25YRS Anniv. issue #28 F/W 2017

Frédéric Mitterrand Olympic Cinema 1971

text by SIMON LIBERATI

All images courtesy of Frédéric Mitterrand

Frédéric Mitterrand, Olympic Cinema, photo Bernard Cotte

Frédéric Mitterrand, Olympic Cinema, photo Bernard Cotte

Frédéric Mitterrand is a brillant writer, popular television host, openly gay personality, and former French Minister of Culture. One thing has remained unchanged since the beginning of his public career: his fascination with cinema — from the cinema d’auteur to the old Hollywood melodramas. In 1971, he bought a movie theater in Paris to screen obscure and flamboyant films. It attracted true cinephiles, but also drag queens, local thugs, and eccentrics. This is the story of a moment in time when a cinema could be a place to be, an underground social scene, a party.

Frédéric Mitterrand in front of the Olympic Cinema

Frédéric Mitterrand in front of the Olympic Cinema

It was in 1971, in a working-class neighborhood of southern Paris, that the Olympic cinema first saw the light of day. Back then, movie theaters, and especially art houses and film clubs, still retained the aura of carnivals and magic from the first days of cinema. You’d head to the Cinémathèque at the Palais de Chaillot to attend your black mass: the showing of an old silent by Erich von Stroheim or Murnau. Sometimes it would be years before a well-worn reel would be shown again. The Officiel des Spectacles, with its weekly listing of show times, was every bit as titillating as a Comédie Française poster was for Proust. Your desire would mount as projection day approached, until at last a flickering movie poster featuring the outmoded, sometimes plump, often strange profile of a Mae Murray, Theda Bara, or Bessie Love took on the feel of an apparition. It was enough to make a believer out of you. Moviegoers would pledge their adoration in silence, albeit separately. Though crossing paths often enough, they would never get acquainted — eyeing one another with the controlled jealousy of connoisseurs.

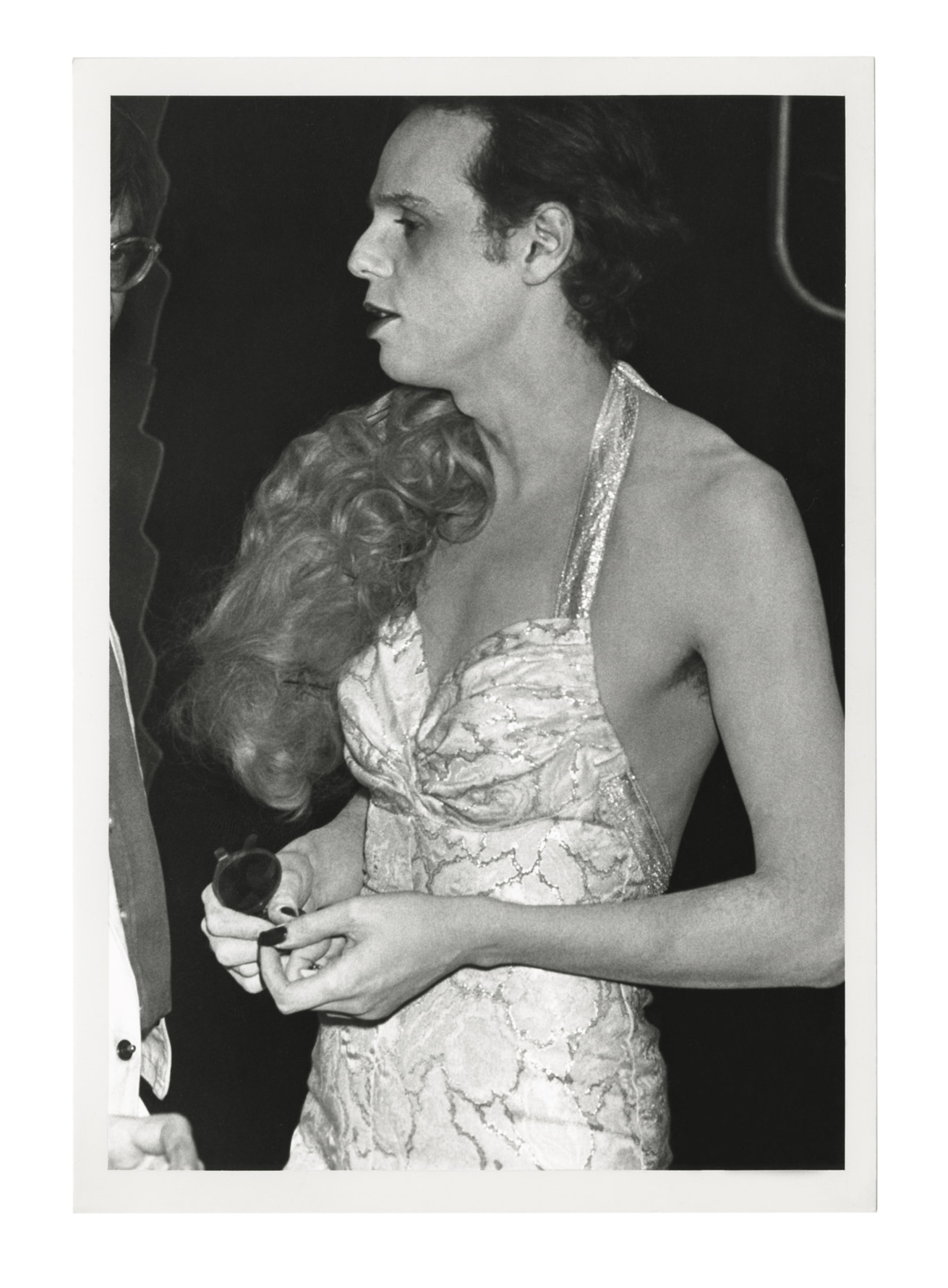

Frédéric Mitterrand, 10th anniversary of the Olympic Cinema at Le Palace, 1981, photo Dominique Lauga

Frédéric Mitterrand, 10th anniversary of the Olympic Cinema at Le Palace, 1981, photo Dominique Lauga

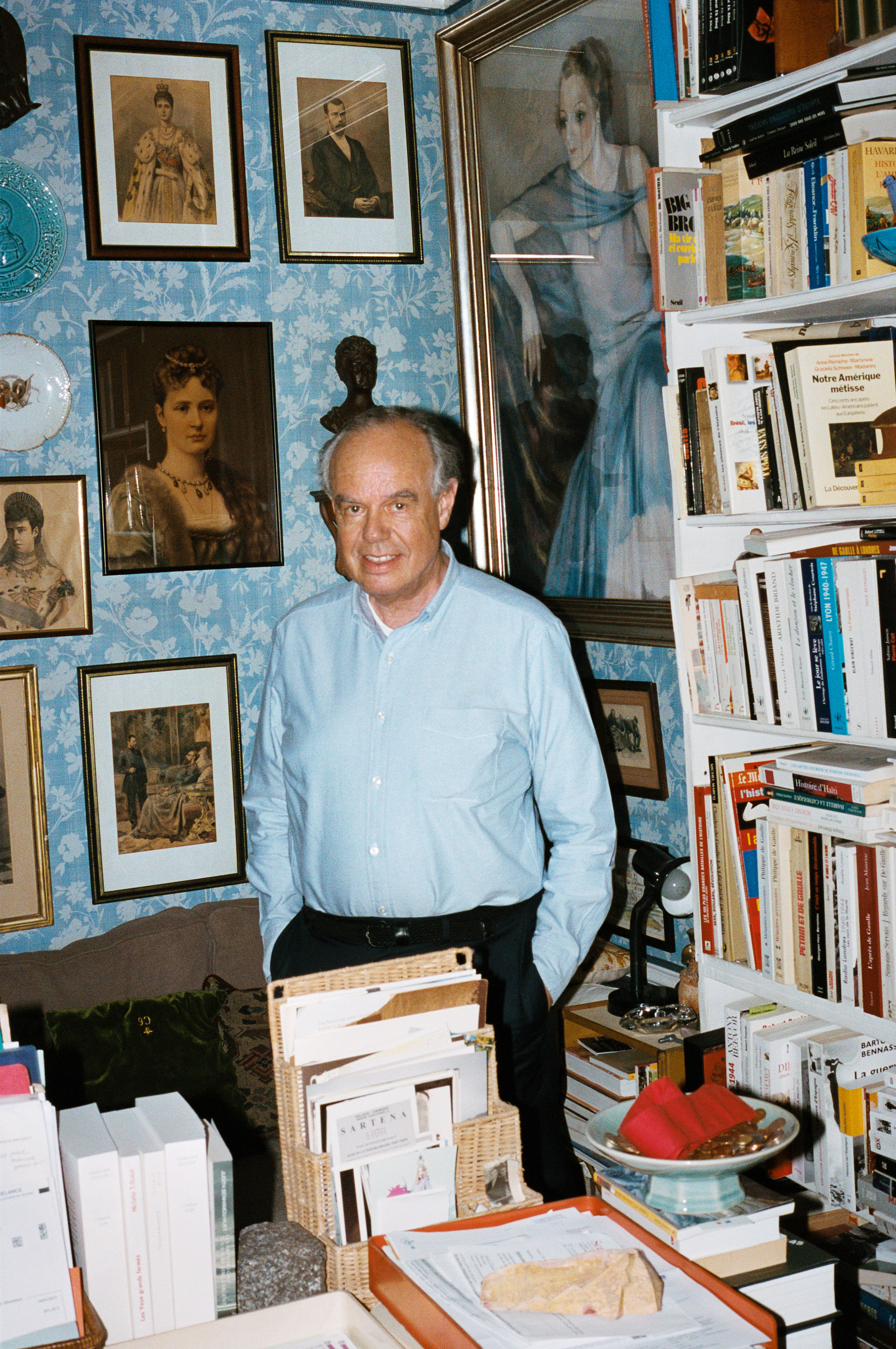

Frédéric Mitterrand at his apartment, Paris

Frédéric Mitterrand at his apartment, Paris

Back then, bulbous, wood-framed television sets would run the occasional gem of an old film, broadcast whole or in excerpt on a show called La Séquence du Spectateur, by France’s one channel, ORTF (Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française). The excerpts were even more beautiful than the full films, as they left something to the imagination: a measure of invisibility that fed into the sacred.

In buying an old theater on Rue Boyer Barret in the 14th arrondissement, with 15 million old francs (about €10,000) borrowed from the father of one of his students, a young man named Frédéric Mitterrand founded a new church. He was 22, a bourgeois from Paris’s bourgeois 16th arrondissement, who venerated his mother and famous actresses from the past. Like Fassbinder in Germany, and at about the same time, he had a taste for Hollywood melodrama and 1940s stars like Lana Turner, Ava Gardner, and Simone Simon. Unlike Cinémathèque archivist and director Henri Langlois, or the film critics from Cahiers du Cinéma, Mitterrand, with his chic and instinctive retro tastes, was drawn to film’s forgotten classics.

Cinema was still culturally important in the early 1970s. It was leaving the Godard-Antonioni period and looking to the past, as in Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde or Visconti’s The Damned. This allowed the narcissists of the day to dig themselves an abyss and develop the decadent culture then taking shape more or less everywhere: on the margins of leftism, in Maoism, and in all manner of revolution. Bourgeois ideology had recycled its old poisons and was now selling them as overstock. Saint Laurent’s recut Gestapo countess dresses of 1971 popped up alongside the military-surplus uniforms worn everywhere. Old films were dusted off and recycled in thematic “retrospectives.” The Olympic would become their temple.

María Félix and Frédéric Mitterrand, 10th anniversary of the Olympic Cinema at Le Palace, 1981, photo Dominique Lauga

María Félix and Frédéric Mitterrand, 10th anniversary of the Olympic Cinema at Le Palace, 1981, photo Dominique Lauga

Mitterrand, a young guru and opiate-of-the-masses dealer, was a Neuilly fop with a shock of hair and tailor-made jackets. But there was a touch of pop about him, a hint of the gigolo, and a slight effeminacy. His peculiar elocution alone ought to have set him at odds with Marxists, radicals, and feminists. Yet he ended up bringing people together in his bizarre cinematic church, one of the most deliciously broken-down havens of 1970s Paris, a locus for youth who chose fascination over revolution.

Death by overdose was not uncommon at the Olympic, as heroin mixed well with film noir.

The same aura of mystery surrounded the cinema stars, whose hard-to-find biographies were always in English. Bereft of behind-the-scenes knowledge, audiences sat on ruined springs upholstered with musty velvet and fed themselves on the apparitions of a storybook world.

In his book Mes Regrets Sont des Remords (My Regrets Are Remorse), Robert Laffont, 2017) Mitterrand tells the story of an Olympic regular, a mysteriously shady, half-fading ’40s lesbian, a Modiano-esque vamp he lodged in his house a few months before she died in a hovel, devoured by rats. His theater’s usherettes, like the lovely African woman named Zohra (pictured), were among the first female immigrants to hit the Parisian scene. Thus, the flowering of the proletariat mixed with Cinémathèque buffs and famous directors. François Truffaut met Mitterrand selling tickets at the Olympic’s front desk, steering his cinema friends to the Rue Boyer Barret.

Frédéric Mitterrand and Zohra, Olympic Cinema

Frédéric Mitterrand and Zohra, Olympic Cinema

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND

interview by SIMON LIBERATI

portrait by OLIVIER ZAHM

Without a single subsidy, the Olympic expanded and scraped by. Its disreputable air cast a peculiar vibe against the young proprietor’s ties to a future president of the French Republic, François Mitterrand. The place was given “official” recognition under Minister of Culture Jack Lang — a ministerial post Frédéric Mitterrand would later fill.

Despite the young Mitterrand’s career as a writer, filmmaker, television host, and Minister of Culture, there’s something obscure and definitively underground about him. The Olympic closed in the mid-1980s, during the rise of the VHS market, marking the end of an era — the end, in my view, of true cinema, of cinema as black magic. Which he served up so well.

Frédéric Mitterrand lives on the mezzanine of a building in Paris’s Faubourg Saint-Germain, near the National Assembly. From the street, I look up at the blank windows of the adjacent apartment, where Lady Oswald Mosley once lived. For a long time, the customers of the post office next door could spot her small head lying on a lilac couch. In the stairwell, I hear the precious, unmistakable drawl — very 1970s demi-monde — of the former Minister of Culture. He’s on the telephone. The door opens. I step into an apartment from another time. I take a seat on a Louis XVI wing chair.

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — I’ve restored the living room to how my mother had it, like Norman Bates.

SIMON LIBERATI — I’d like to talk about the first Olympic cinema, which you opened in 1971. A sort of Cinémathèque annex, deep in the 14th arrondissement. A magnet for all kinds of cinephiles. You were very young at the time, still a student. How did you decide to buy and operate a movie house in Paris and support a kind of cinema that had no equivalent at the time?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — That’s not quite true, actually. There was Action Studios, near Rue La Fayette, which had already opened three or four theaters by then, as well as several others in the Latin Quarter showing old films and modern American cinema, like Andy Warhol’s films. I arrived on the scene after them.

simon liberati — Your childhood friend Carlos d’Arenberg told me that you bought the Cinéma Olympic with a loan from one of your students’ parents.

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — It’s true. I was working as a teacher at a bilingual school. I was very close to one of my students, the son of the school’s owner, and it was the owner who loaned me 15 million old francs [€10,000] to cover Mr. Wagner’s asking price for a little theater in a backstreet in the 14th arrondissement. It wasn’t expensive. Back then a movie theater was worth about six times that, or about 70 million old francs. It was a rotten place, clearly the cheapest one around. Rue Boyer Barret was very remote and hard to get to.

From left to right, in the front: Sonia Saviange,<br />Suzy Delair, Virginie Thévenet, Isabelle Huppert, and Nathalie Baye in the back: Hugues Quester, Béatrice Romand, Dominique Labourrier, Simone Simon, Paulette Dubost, Frédéric Mitterrand, Annabella, and Nicole Garcia

From left to right, in the front: Sonia Saviange,<br />Suzy Delair, Virginie Thévenet, Isabelle Huppert, and Nathalie Baye in the back: Hugues Quester, Béatrice Romand, Dominique Labourrier, Simone Simon, Paulette Dubost, Frédéric Mitterrand, Annabella, and Nicole Garcia

SIMON LIBERATI — You were 23 years old and had been born into a very bourgeois family. Why become a theater operator?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — I was looking for a way into the movie business, but I had a problem. I’d developed a fear of film crews after serving as Michel Deville’s assistant for the filming of Raphaël ou le Débauché. I hadn’t enjoyed playing the hanger-on every night. Just before buying the Olympic, I worked for nine weeks without pay during the summer. I decided to quit one week before the end of the shoot, and the production director, Philippe Dussart, said to me, “You’ll never work in movies again.” It was a hard thing to hear. The only option left to me was to open my own movie theater. I signed the papers the morning General de Gaulle died.

SIMON LIBERATI — Right away you put your stamp on things.

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — I screened a Greta Garbo film and then Splendor in the Grass, an un-dubbed Elia Kazan melodrama. Mr. Wagner’s last customers stormed out, furious.

SIMON LIBERATI — Did new customers start to show up?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Yes. Truffaut said some nice things about me. I’d handle the cash box myself in my office, and that established a rapport. The cinephiles started coming. Then the bourgeoisie, slumming. It was a dangerous area at the time. There were gangs of thugs who’d get in through the exits and steal the usherettes’ Eskimo Pies.

SIMON LIBERATI — Were they Hell’s Angels?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Yes. They were loulous, hoodlums. I was the one who eventually turned them around. One day during a screening I turned up the lights and spoke to them, and thereafter they adopted me. They even helped me fix up the theater and gave me protection.

SIMON LIBERATI — You were a real diplomat.

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Yes. For a guy from the 16th arrondissement, I’ve always been good at that game. There were some handsome fellows. My friend François Wimille [husband of filmmaker Catherine Breillat] thought them divine. Later they started attracting the travelos, the drag queens. The Gazolines among the intellectual transvestites.

SIMON LIBERATI — Marie France’s gang?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Yes. Hélène Hazera, Maud Molyneux… Delightful people, highly cultured. I really liked Hélène Hazera, insofar as you can like someone that nasty. She refused to shake my hand the last time we crossed paths, three weeks ago, because I was using the word “travelo” — the language of the enemy. I told her I’d have loved to be a travelo!

SIMON LIBERATI — It was a very political time. What were you screening?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Mostly old films, but in themed retrospectives: “Flamboyant Melodramas,” or “Naughty Children.” In 1974, a loan allowed me to do some refurbishments, and I created a second, smaller theater. I inaugurated it with a party, with Jean Seberg on hand. After that I could show my themed series while also showing art films that couldn’t get a screening elsewhere. I recall a tribute to Bill Douglas. It was produced by a far-left group from England and drew pretty well. This was also the heyday of Adolfo Arrieta. Switching gears, we did an evening with the prostitutes who staged an uprising. We got some press for that.

SIMON LIBERATI — Problems with the police.

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Yes, often. I was even taken to court over some evenings organized by ultra-left-wingers. I remember this one crazy night. Since the place had become fashionable, Charlotte Rampling was in the lobby doing a photo shoot for Vogue. Meanwhile, in the theater there was a soirée organized by the Gouines Rouges, a gruff splinter group off the MLF [Women’s Liberation Movement]. So this bull dyke comes out of the theater to pee and sees Charlotte on the staircase with a fur coat on. The dyke has a whistle around her neck, and when she gets a load of the depraved scene, she starts blowing the whistle as hard as she can. It was deafening. So now all the Gouines Rouges come bursting out of the theater. And that’s when the trouble starts.

SIMON LIBERATI — On a more serious note, which filmmaker are you most proud to have stood by during those years?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Egyptian cinema. I was the only one outside the Barbès circuit to show Egyptian musicals. And Ozu, whom I helped people rediscover before the Cinémathèque. After a cinephile found me the reels, I did an Ozu evening presented by Wim Wenders.

SIMON LIBERATI — After a memorable evening at the Palace for the Olympic’s 10-year anniversary, with Mexican star María Félix on hand and you yourself dressed in drag as Lana Turner, you went bankrupt in the 1980s, right?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — Yes, in ’86. Expanded too fast, had too many branches, and never got a dime in subsidies.

SIMON LIBERATI — Why?

FRÉDÉRIC MITTERRAND — It didn’t occur to me to ask. When I became Minister of Culture, I came to understand that the only people who get money are people who turn themselves into a damned nuisance. The ones who insist, who demand. Nice, timid people get nothing.

END