Purple Magazine

— F/W 2016 issue 26

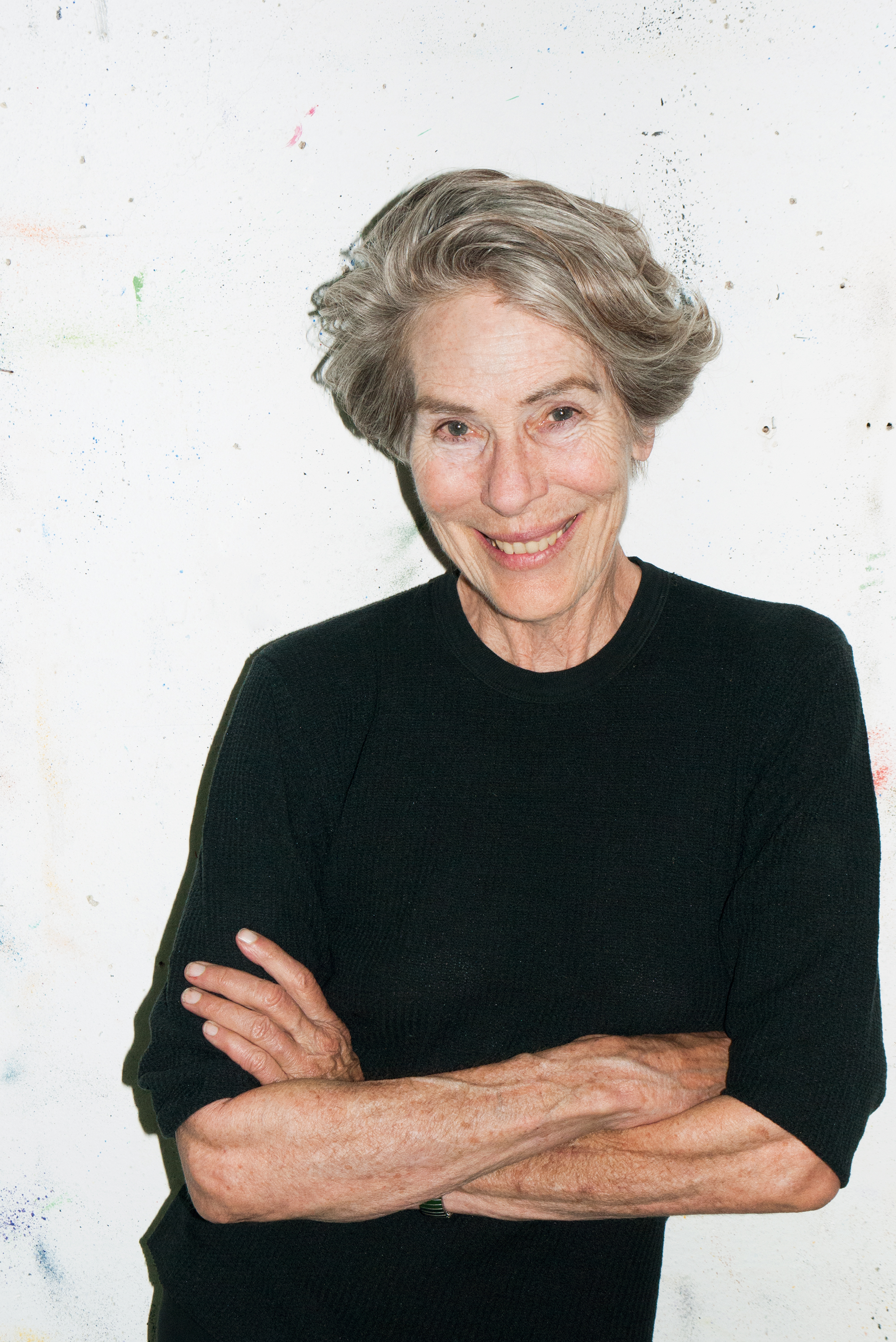

Mary Woronov

from superstar to anti-star

interview and portraits TERRY RICHARDSON

Of all the girls at the center of Andy Warhol’s Factory, “superstar” Mary Woronov was the one who played the tough guy. Moving to Los Angeles, she performed in dozens of B movies, including Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000 (1975) and Eating Raoul (1982), and Roger Corman’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (1979). Later she appeared in the television series Charlie’s Angels and Knight Rider. Artistic Mary — she’s an author and exhibiting painter, and was an actor in New York’s Theater of the Ridiculous — always resisted the Hollywood establishment, preferring non-commercial cinema experiences. Terry Richardson, a true fan, photographed and interviewed this free spirit at her home in Los Angeles, where she lives, writes, and paints.

TERRY RICHARDSON — What was it like working before the Internet and smart phones and all that? It’s funny — in the midst of conversations, people look at their phones. That’s all people do. It’s constant distraction.

MARY WORONOV — I hate smart phones. They’re changing everything: the language, the concentration, the stories. There is no language, just symbols. It’s all dissolving. They answer in monosyllables, and then I talk in monosyllables. I don’t talk to anybody anymore. My vocabulary is pathetic at the moment. Do people read any more? I desperately miss the loss of language.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Where were you born?

MARY WORONOV — I was born in The Breakers hotel in Palm Beach, Florida. My grandmother lived in Florida. I’d go back in the summertime. I never really got loose from Florida. But, things were a little rough. My mother didn’t have much money. Then she married a Jewish doctor from Brooklyn, and things straightened out, fabulously. He was salt of the earth. Suddenly, at six, I was in a private school for girls. They never spent much money on clothes, only on schools, lessons, things like that. Mom had a son and did not have time to take care of him, so he was mine. And to this day, Victor and I are very close.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Your little brother. How many years apart?

MARY WORONOV — Eight. Victor was born on my birthday. Dec. 8. I built the inside of his head. I did everything with him. You name it.

TERRY RICHARDSON — A brother born on the same day…

MARY WORONOV — It’s my day. He’s terri c. And exactly my opposite. He’s a boy. I’m a girl. He likes music. I like painting. He’s married with two kids. I got married twice, but for only five minutes. So, we’re opposites, but we really like each other.

TERRY RICHARDSON — How would you describe your childhood?

MARY WORONOV — Well, from the time she married the good doctor it was — it wasn’t high class, but it was up there. I went to this amazing, really expensive all-girls school. Girls should only be educated with other girls because boys suppress them. I loved it. It taught me everything. I read books that people hadn’t read. I had Latin, French. They let me write. They let me act, on stage. They let me paint. I was known for painting. It was good for me. I had no problems with ego. The only thing wrong is that you had no idea about sex — I mean in the ’50s. But I got smart and then went to Cornell [University].

TERRY RICHARDSON — I watched your Screen Test. It’s so beautiful. How did you meet Andy Warhol?

MARY WORONOV — Gerard Malanga came up to listen to poetry or to read poetry and saw me in a play at Cornell and started tracking me: “Hey, want to do this?” I never understood he wanted me to be in Warhol’s movies. I was attracted to Gerard, and he pretended to be attracted to me. Warhol wasn’t using him that much. He thought if he was with a girl who was really talented, he would be used more. It was his way to be in front of the camera more. I realized that years later. I was so stupid. But I didn’t want to leave school and go back to New York. Then, Cornell decided we should go to artists’ studios. We went to [Robert] Rauschenberg’s bright and cheery studio, all white, hip-looking people around — hippies. Then we went to Warhol’s dark, dirty studio, painted black, with some tinfoil, and two drag queens on a sofa clowning around to upset everybody — and these amazing-looking gay men. Then Gerard came out of nowhere and said, “Warhol’s going to do a movie. I think you should stay around because I think he’ll want to shoot you.” I said, “Okay.” My class left, and I stayed.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Just like that.

MARY WORONOV — Gerard put me on the stool, far off, and said, “This is a screen test.” I said, “Okay.” Then the camera turned on, and everybody walked away. So I’m facing a camera, thinking: “You think I’m so beautiful. Okay, they’re making a joke. They want to see how long I’m going to sit here with an empty camera going.” I was totally paranoid. And then I thought: “Okay, all right, Mary, it’s a joke. You’re not getting hurt. Maybe there’s lm in the camera — you’d be stupid to walk out if there was lm in the camera.” So I calmed myself down. Then I’d get paranoid again because a long time passed. But then I saw Nelson [Lyon] do it. All of a sudden, his eyes picked up, and he was like a snake. I don’t know what the fuck he was thinking about, but he was great. He was evil, which is always hypnotic.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But from that, you did the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable,” dancing with the Velvet Underground. How did that happen? MARY WORONOV — After that, we were supposed to do a show with three artists — Rauschenberg was one — and all these hippie girls skating through a movie screen that had slits in it. We came on, and then the Velvet Underground was warming up and played “Heroin.” We loved it.

TERRY RICHARDSON — First song, and they played that?

MARY WORONOV — That’s the song they played for Andy. He didn’t even know them. They just came in, almost like an audition.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Like this is what we do, this is who we are.

MARY WORONOV — He hired them right away. He said, “I want to help you.” I don’t know what happened. But there they were. So the next time we performed, with Rauschenberg, they were there but pissed off, so nobody liked them. They were used to that, and turned their backs and made feedback noise, and that was the end of that. Everybody was upset. But then they performed more and more and became part of the group. By then, Gerard decided they were boring to watch, which they were, so he would dance. Gerard would make up these routines, like for “I’m Waiting for the Man,” and I would lift weights. For “Heroin,” Gerard had a dayglow plastic syringe he would dance with. For “The Black Angel’s Death Song,” we used whips. It was all about caressing. It wasn’t about hurting.

TERRY RICHARDSON — What did you wear?

MARY WORONOV — We always wore the same thing. He bought me a pair of black leather pants, and I wore a black top — and boots. We always wore boots.

TERRY RICHARDSON — So why were you with Warhol?

MARY WORONOV — I mean, what happened is a long story. When I was at Cornell, I had a great history teacher. She said I had to read Mary Renault’s The Last of the Wine — about gay people. They were so sexy to me. Don’t ask me why. I also read, you know, [Emily] Brontë’s Wuthering Heights — Heathcliff and everything — and Genet. But I didn’t know even one gay person. My mother was against them. I thought they were the sexiest in the world. At Cornell, I also always had boys after me, and I really hated them. It was not fun. Warhol’s sexy drag queens fascinated me. I became part of the group; so for my turn — because you have to do something when you’re with Warhol — I played a man. They walked up to the table, and I pulled out a chair for them. They pulled out a cigarette. I lit it. I became really good at playing a man. I was subtly aware of the fact that for some reason, I looked really sexy playing a guy. Not like a lesbian or like I was playing a joke, just being more brutal, and not pleasing like I was daddy. I t perfectly with drag queens. They were fabulous women. I was a fabulous man. It was just a sideshow, and so funny, we’d crack up. But then other people started doing other things. Like Ronny Tavel’s Theatre of the Ridiculous. When he asked me to do a play, I knew exactly what he wanted, which is what I was already doing — theater.

TERRY RICHARDSON — What was the first play you did?

MARY WORONOV — I’m not sure, but the best one I did with them was Kitchenette. I played a woman married to a guy I ignored. I was in my own world. And he was desperately trying to tell me that he just had an affair with a guy, and maybe our marriage was over and maybe it wasn’t. And then I would blow up at him. So it was funny and not funny because the Theater of the Ridiculous was like life. They were into not doing what you’re supposed to onstage. You could step off the stage, scream at the audience, do whatever you like. The director John Vaccaro was brilliant. He would use a half-gay, half-not-gay chorus line, which was unheard of then.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Even the premise, for the time, was very transgressive.

MARY WORONOV — It fascinated people. I lived a theater life that nobody knows about now. I think it was the most brilliant thing I ever did. Everything after was downhill. You could talk to the audience. You could make love with the audience if you wanted to. You could do whatever you liked. I’m not so sure it would go over well now because people are used to that kind of thing. Rauschenberg was like that. But people said Warhol was weird. Andy threw it in their faces. He was great.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Do you feel that Andy Warhol was performing all the time?

MARY WORONOV — Yes. I have a book called Uncle Andy’s, about the children in the rest of Andy’s family. He was like Uncle Andy. He was fine. He didn’t do weird things with us. The problem was, the more he did them outside, the more trapped he became in that persona. But he also engendered fierce loyalty in us. We’d get rock-bottom mad if somebody touched him, if somebody said the wrong thing. I was in Italy doing a movie when I found out that Warhol had been shot. I felt such guilt, like I’d abandoned him, like it was my fault.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Because you had such a strong connection with him?

MARY WORONOV — But we hardly even talked. He didn’t talk to anybody, really, except to Brigid [Berlin] — I never heard someone go on about hair in such a way.

TERRY RICHARDSON — He created that energy in people, in that environment, like a family.

MARY WORONOV — We were called the mole people — night, dark glasses.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But he orchestrated that world.

MARY WORONOV — I don’t know if it was his idea or ours or if it simply happened… Lou Reed should have married Andy. Lou Reed was like a part of him. It was like a father relationship of some kind.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Was there a competitiveness?

MARY WORONOV — Fierce.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But if you found your own role, then everyone had a place, right?

MARY WORONOV — People had to act a certain way. And, you know, there were people who were under you, the gray people, who weren’t allowed in the building, who stayed outside. It was ruthless. We all had names. Ondine was the Pope.

TERRY RICHARDSON — What was your name?

MARY WORONOV — He wanted to call me Mary Might because I was so strong, but I wouldn’t have it. You know: girls play weak, I played strong. But I wouldn’t have a name. I didn’t want it.

TERRY RICHARDSON — How did Chelsea Girls come about?

MARY WORONOV — Andy was, in a certain way, also part of the Theatre of the Ridiculous. He knew them and was doing movies where everything was different, breaking all these barriers. You didn’t have to have a costume. You didn’t have to learn lines — there weren’t any. You didn’t have to act straight. You could do what you wanted. Because of the class of people that surrounded him, peculiar things happened. We threw a lot of people out. They sort of understood the laws, but of course there were no laws. What he wanted was to do a movie where the camera went on forever. He did a lot of movies like that, but Chelsea Girls was a compilation of movies strung together. So it had an interesting weirdness, with someone just sitting in front of the camera.

TERRY RICHARDSON — And you knew your lines.

MARY WORONOV — Yes, I did. Not only that. I would fuck up and then do the same fuckup night after night because it got a laugh. I was very conscious of my audience. I’ve always been that. Even in the first movie, the Screen Test, I was conscious. That’s why they liked me, or that’s why Warhol liked me. I’m not sure how much they liked me. Except for Ondine, who liked me. I loved him. He was great.

TERRY RICHARDSON — When you did those films, there was no takes?

MARY WORONOV — No. No takes. No lines. Just the camera running. There’s nothing Hollywood about them.

TERRY RICHARDSON — So how long did that go on for?

MARY WORONOV — I don’t know, a couple of years.

TERRY RICHARDSON — When did you come to Hollywood?

MARY WORONOV — I got the Theatre World Award for doing In the Boom Boom Room at Lincoln Center, which proved that I was an actress. Then, in order to make money, my agent told me that I had to do soaps, which was a disaster. So my husband’s best friend, Paul Bartel, and I saw a movie of his that made me so paranoid, I couldn’t speak to him for about a week. It was called Secret Cinema. It was brilliant. He’s talented. Then he goes to LA and writes to say he has a role for me in Death Race 2000, working with Roger Corman. So he brought me to Hollywood, gave me that role, and the rest is what happened. I worked with Corman a lot. I liked him.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Death Race 2000 is a brilliant lm — Sylvester Stallone, David Carradine…

MARY WORONOV — Yes, it’s incredible.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Every time you drive, you’d see pedestrians and think, “How many points?” For years, that lm stuck with me.

MARY WORONOV — There was a sense of humor in the movie, too. Paul’s good at humor, too. It was a car movie, and I couldn’t drive. I’m from Brooklyn. I take the subway. I’d pretend to drive. I had to wear a helmet because that’s what stunt drivers did.

TERRY RICHARDSON — That’s your first Hollywood movie? Do you drive now?

MARY WORONOV — Of course. I got very married. I tried to be very married. And then punk rock happened, and forget it. I bought a Trans Am. I was lethal. I started taking drugs again. I went nuts.

TERRY RICHARDSON — This is Hollywood in, what, the early ’80s?

MARY WORONOV — Yeah.

TERRY RICHARDSON — The music scene was incredible then?

MARY WORONOV — No one knows about it. No one cares about it. What’s wrong with people? They never mention the California music scene. It was phenomenal. Absurdly so. I was having a second childhood, like being back with Warhol. It was so stupid and so fabulous and insane.

TERRY RICHARDSON — What bands did you like?

MARY WORONOV — Bar none, X — Exene and John Doe. Exene’s voice was like you stepped on a cat’s tail. It was so Los Angeles, so brilliant. The other one is Billy [Zoom].

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah, there are so many great punk rock bands from that era.

MARY WORONOV — Fear. Suburban Lawns — a killer. You know that [Latino] band The Plugz that did nothing but play “La Bamba”? I did the video for the song [that goes] “Give me a Pepsi, Mom, all I want is a Pepsi.” I got an award for that.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Suicidal Tendencies. “Institutionalized.” It’s an incredible song, video, band, the whole moment.

MARY WORONOV — Yes, great band. I loved them.

TERRY RICHARDSON — And you did their song, “Possessed to Skate,” which…

MARY WORONOV — Yeah, which had Timothy Leary in it, too, right?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah, that’s an incredible moment in Los Angeles.

MARY WORONOV — There are three that I like: The Doors, Lou Reed, and Bowie.

TERRY RICHARDSON — You did Rock ’n’ Roll High School, playing Miss Togar, an incredible character. I was in New York then. I remember seeing it 15 times in a row in the 8th Street Playhouse. It’s such a good lm. I was obsessed. Miss Togar’s character had a profound effect on me: I’m, like, who’s this woman?

MARY WORONOV — I did not think that up. I was going to play in a series on TV, Our Miss Brooks. I was married. I had not left my husband, so I didn’t know about punk rock yet. That’s why I decided to do that movie. But anyway, so I get on set, right? I’m all ready to do Our Miss Brooks, and the fucking punks — I couldn’t believe it. I mean, rooms full of them. The band was just moronic. But they were fabulous. I turned into something I didn’t understand. Then once I started, the whole thing came back. It was so nuts. I left my husband before the movie was over. I started painting, and I lived on Western Avenue, and I was at every fucking punk gig, and I started fucking around. Which wasn’t so good. But it was great.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Did you go to the Zero and those clubs?

MARY WORONOV — I lived at the Zero. It was a fucking great place, standing ankle deep in beer and piss. El Duce used to walk around, and if you had passed out, he’d whip out his dick and piss on your feet. I mean, it was so stupid, it was just incredible. Every night. There was an explosion of creativity. It’s because every kid had a garage band. It wasn’t like New York where they were playing certain places. I remember standing in the street, waiting to go into a club, getting high, kids hanging around the doorman: “We don’t have any money. Can’t you let us in?” All of a sudden, there were gunshots and a siren. These kids put their hands in their pockets: “Here’s $50. Let us in.” Everybody was pretending. My boyfriend got beaten up at the Starwood. Did you go to the Starwood?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah, the Starwood was great.

MARY WORONOV — Better than the Cathay de Grande — kids standing in the balcony…

TERRY RICHARDSON — Diving off the balcony, jumping into the crowd. Total mayhem.

MARY WORONOV — People destroyed themselves. It was just what I needed, and what I liked. California was a great place. I don’t understand what happened.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Let’s talk a little bit about Eating Raoul by Roger Corman because that came after his Rock ’n’ Roll High School, right? I watched it recently. It’s shot so well, too — the montage of Hollywood introducing characters. It’s so entertaining, so funny.

MARY WORONOV — It’s funny because it’s the Theatre of the Ridiculous.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Are you improvising? Is there, like, a dialogue?

MARY WORONOV — A lot of improvising. The script was stupid. They actually were doing a sex script. I didn’t do a sex movie. But everything was tongue-in-cheek. Paul has a brilliant sense of humor, and he was racing right along with me. But there’s another movie, called Hollywood Boulevard.

TERRY RICHARDSON — I know that lm. It uses a lot of old footage, too. There’s a shot from Death Race 2000, and then it cuts to you walking away from the car. It’s basically Corman footage. Death Race 2000 opens with a crowd shot, which I think was found footage.

MARY WORONOV — Yes. He would use other people’s footage. The two boys who did Rock ’n’ Roll High School, [Joe] Dante and [Allan Arkush], were also responsible for Hollywood Boulevard. They said they could make a movie with just footage. They were cutting trailers. So they had all this footage and made Hollywood Boulevard. It’s stupid but brilliant — except for the two leads. There was no romance. Which was too bad, it might have been…

TERRY RICHARDSON — I love that film.

MARY WORONOV — You’re the only person who’s seen it. They don’t show it anymore…

TERRY RICHARDSON — The scene at the Hollywood sign: it’s got graffiti scratched on it and spray paint all over it, and it’s so destroyed — what an amazing place to lm a scene. I’d never seen that in a lm. How the hell did you get up there?

MARY WORONOV — We did anything. The scene with the airplane, where we look down and then there’s this puff of smoke, is my favorite scene with Paul [Bartel]. It’s all improvised. Everything we did was improvised. He’s really good at improv. I’m semi-good.

TERRY RICHARDSON — You would just show up and just start filming, right?

MARY WORONOV — Yes. I would change my clothes in a telephone booth.

TERRY RICHARDSON — I remember first seeing your films and wondering if you were together because you were always working together.

MARY WORONOV — Nobody else would hire me because I was a Warhol girl.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But in Paul Bartel’s Eating Raoul, you play “Mary” and Paul plays “Paul” and you’re in couple.

MARY WORONOV — Yeah. I finally played somebody I liked.

TERRY RICHARDSON — So you were just friends?

MARY WORONOV — Okay. So I’m going to tell you this. I’m going to tell youajoke.PaulandIdidalotof interviews after Eating Raoul, and he kept on saying, “We’re married.” And I’m going: “Paul, I can’t get a job if you say we’re married. Nobody hires somebody’s wife. I don’t want you to say it anymore.” And he said: “We’re married. We’re married.” I said I’d call his parents and tell them he’s queer. And then he calls me and says, “I’m also never going to interview with you ever again.” Bang! Then he calls me back and says: “Mary, be very proud of me. I called my parents and told them I’m gay. But I’m still not interviewing with you.” Then he calls later and says, “Mary, there’s a New York interview, and it’s very important to us.” And I go, “No.” “Well, what if I promise never, never to say that we’re married again in an interview?” I say: “Okay, ne. Let’s go to New York.” So we go to New York, and the woman goes, “And you’re both married, aren’t you?” And Paul goes, “No, we’re divorced.” I fucking hated him. Like, I was going to kill him.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Perfect.

MARY WORONOV — I know you like him. But that pissed me off. A lot of work lost. That’s the only time I ever went against him. I really have lots of respect for the guy, and I did whatever he wanted. But I waited until he was dead to tell that story.

TERRY RICHARDSON — He passed away recently.

MARY WORONOV — Yeah. He was a really great guy. He worked a lot. I didn’t get any work.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But you did a ton of TV, Charlie’s Angels, so many different shows and things. What was that like?

MARY WORONOV — Taking jobs. Work I never got a rush from like with the Theater of the Ridiculous, Warhol’s movies, and working with Paul. I’ve never been able to replace them, except on Eating Raoul and Rock ’n’ Roll High School.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But I feel that you’ve always been working.

MARY WORONOV — Dogs. I don’t like it anymore. Otherwise I’d still act. Hollywood is just not for me. I’m so Theatre of the Ridiculous. I need to be against something. You know, now everything is wonderful.

TERRY RICHARDSON — I thought The House of the Devil was a great film.

MARY WORONOV — It’s a good lm, but I’m not that good in it. I don’t know. It’s over for me. I like painting, and I love writing, except I have writer’s block right now. They don’t do those types of films anymore, and if they do, it comes from a very knowledgeable place, and it’s not risky.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Tell me about your paintings. You’ve been painting for a while, right?

MARY WORONOV — I’ve painted all my life. My mother used to leave, and the way I knew she was going to leave was she would give me crayons: “Do this. I’ll be back by the time you’ve finished,” or whatever. So you occupy yourself. I used to think I could change the world, and that if I did a really good picture, she would come back. I used to believe that just to help myself. I was very fragile when I was young.

TERRY RICHARDSON — You have another art show coming up, right?

MARY WORONOV — Yeah. I too am story-driven. All of these paintings have a story behind them. They are illustrations. I know that’s a bad word for a painting. But the problem is, if there’s a story, then I can paint. I can’t just paint. It has to be something that I can put movement into. It’s weird. I’m way out of whack. I have no place in this world. I mean, all of these paintings have some kind of story. This painting shows how I feel when I’m acting — naked, with a bunch of jackals looking at me.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But you come off strong and powerful. Is that also being vulnerable, or exposed?

MARY WORONOV — Exposed and vulnerable — oh, poor Mary, right? Well, it shouldn’t be poor Mary because I don’t mind being exposed and vulnerable. And my audience, even if they don’t get it — not that I’m smarter than they are or anything — I mean, even at the TV auditions, you feel completely ignored.

TERRY RICHARDSON — But now it’s changed, right — television, writing?

MARY WORONOV — TV has really gotten to be great. Game of Thrones is fabulous. But I don’t have a television. I don’t watch it. I go to the movies. But movies suck. There aren’t any good movies. It’s weird. I mean, I know it’s about money because we’re actually entertaining the world, and the world doesn’t want to watch Kim Novak or Gary Cooper. They want to see Mr. America. It’s okay. But there’s no excuse for the art of movies. For centuries, people said things through art. Now it’s about not saying come to my show.

TERRY RICHARDSON — How does painting make you feel?

MARY WORONOV — I fucking love doing it. I mean, look at that one. What does her face say? “You know, I’ve been married to this guy for nine years, and that’s the worst bathrobe I’ve ever seen. I don’t feel like fucking you.” Most of my stuff is also a joke. I love funny things. But that one’s not a joke. That’s Cain and Abel. I hate religion. But is this guy here putting on his pants or taking them off? He’s in such a frantic rush, you don’t know what he’s doing. I love that. I thought, “Okay, I’ll be conceptual.” So this is what I did. I painted a series: this red line is doing something that the painting is not. And then I thought, you know, that’s probably true. If you put two men in a room, it becomes about sex. And then there’s [Édouard] Manet’s painting, Olympia. But if that were a man lying on the couch, it wouldn’t be the same.

TERRY RICHARDSON — I love this one by the pool…

MARY WORONOV — It’s about [David] Hockney, who painted gay sex, badly. Well, this is not gay sex. It’s a child thinking of fucking his mother when she’s sunbathing. You have these thoughts. He’s jerking off in the swimming pool, so it’s a painting about sex, you see? The last one is total porn.

TERRY RICHARDSON — I’ve never seen a painting like that.

MARY WORONOV — Of course not. Who would paint like this?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Only you. It’s great. It’s powerful.

MARY WORONOV — You see her face? Her face is great.

TERRY RICHARDSON — What’s the last book you wrote?

MARY WORONOV — Oh, the books. I wrote a book about Warhol called Swimming Underground [Swimming Underground: My Years in the Warhol Factory]. This one, Blind Love, is short stories about love, mostly about guys. Guys are so weird. [Laughs] This one’s about California. Niagara’s about being married.

TERRY RICHARDSON — You’ve had quite a few books.

MARY WORONOV — Yeah. I’m a good writer. My next one is almost done, and it’s about punk rock.

TERRY RICHARDSON — How did that nude picture of you and Hervé [Villechaize] come about? It’s an incredible image.

MARY WORONOV — I knew this really rich girl. Her husband was taking my photograph, but he wanted to take it in a loft. I didn’t have a loft, but Hervé did, so I called him up, and he took a couple of pictures of me and Hervé clamming around. We’d do things like get into a crowded elevator together, and people would look at me because I was sort of gorgeous, right? And they would hear a little, tiny voice saying something like, “Mary. Would you fuck me now?” And I would go: “Oh no. No, no, no.” And he’d just be there. It was hysterical. We used to turn people on that way. It was fun. He’d carry a knife and say, “Mary. I’ll kill anybody who touches you.”

TERRY RICHARDSON — Oh, wow.

MARY WORONOV — There’s another one where I’m nude, and he’s leaning against me as if I’m a streetlight. I don’t know. It’s all connected in a way.

TERRY RICHARDSON — How so?

MARY WORONOV — Number one, I don’t have a child. My brother has a child. I think having children is kind of difficult. I’m happy because I’m alone, and I don’t feel bad about it. I’m happy because I can do what I want, and I can paint, and I love my paintings. Writing’s a bit of a problem now, but I’ll get over it. I get up in the morning. I go to this group of people who sit around a coffee shop in Larchmont, Peet’s. It’s just like old Brooklyn. None of them are on their cell phones. Then I come back here and paint. I do what I want. I write articles. My life is good now. I sometimes worry something awful is going to happen, you know, war or natural disaster — because I can’t believe how nice it is. I know the world is not nice. People are having terrible problems. But this place is la-la land — freaky, weird.

TERRY RICHARDSON — When you have downtime, what do you do with yourself?

MARY WORONOV — I daydream, or sleep. My downtime is sitting and thinking. Things run through my head, and I go over and over them. I’ve done this all my life. As a child, I’d sit in the car and stare out the window as my parents drove. And they drove. God, I don’t know what they were driving away from, but that was how things happened in my head. I used to have sex a lot, but I don’t have sex anymore. I’m not afraid of being alone, either. I do well alone. I can get really annoyed by other people.

TERRY RICHARDSON — What about being in a relationship?

MARY WORONOV — I last four years, and that’s it. I’ve tried them one, two, three, four times. Two of the times I was in love. But I was not myself. I did things I can’t believe I did. I couldn’t think. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t do anything — for four fucking years. And then I had two years with somebody I really liked. I wasn’t in love. But I liked them very much. It should have worked. Then all of a sudden I wake up, and I’m out.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Was there a great love in your life?

MARY WORONOV — There’s the person I was most in love with, but it didn’t work out. He was a writer — he wrote plays. The other one was a fucking punk. That was ridiculous.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Out here in Los Angeles?

MARY WORONOV — Yeah, 40 years old, I’m driving around in my Trans Am with this jerk. I loved him bottom down. He was great. But it didn’t last. I mean, he had no money. He was an artist. What artist has money? He worried, and him worried was not a pretty picture… I don’t understand guys that much. It was stupid. I was possessed. I don’t know. But it was fun. Now, I can’t stay in the same room for more than a couple of days with someone. I don’t know what’s wrong with me. You know, in and out, in and out.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Do you find that when you get married, it changes the dynamic in a relationship?

MARY WORONOV — It does. He’s gotta fight. Always fighting. He’s fighting for you. He’s gotta track you. He’s gotta lay you. Then you get married, and it’s like, okay, she’s mine. Ted [Gershuny] never cheated on me. But Fred, who gave me the Trans Am, he was in the business. He cheated on me the first day.

TERRY RICHARDSON — He was the guy with the pool.

MARY WORONOV — Yeah, and a gorgeous house. Then two minutes later, another gorgeous house and another pool. He cheated the day he married me. And you know some- thing? I thought it was funny. I immediately went shopping and found someone else to fuck. We lived like that for a long time.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Where you both had different lovers?

MARY WORONOV — Yeah. And I still fucked him. It was interesting. But the problem was I fell in love, and I had to get rid of him.

END