Purple Magazine

— F/W 2014 issue 22

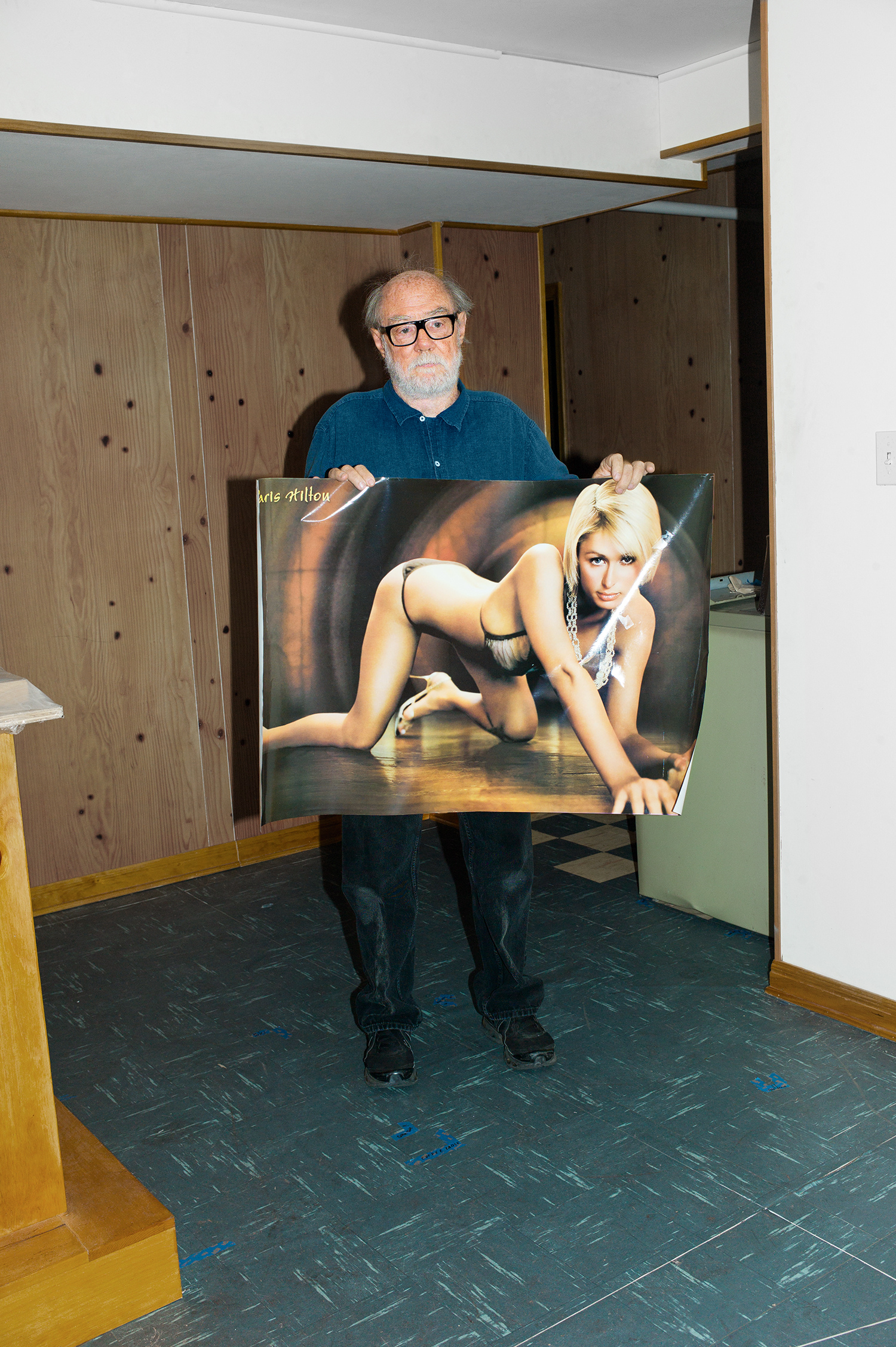

Paul McCarthy

Studio portrait in Los Angeles by ARI MARCOPOULOS

Studio portrait in Los Angeles by ARI MARCOPOULOS

interview by DONATIEN GRAU

portraits by ARI MARCOPOULOS

Paul McCarthy may be the most radical American artist — the devil to Jeff Koons’s angel. He subverts what he calls “normality” through the use of transgression, regression, and repression and creates a “trauma theater” for the art world. Welcome to America’s dark side.

DONATIEN GRAU — You come from Salt Lake City, and your childhood has been a very important part of your work until today. Can you tell me a little bit about it?

PAUL MCCARTHY — It was a type of conditioning. Not too much different than a lot of conditionings in America at that time in the 1950s. But there were particularities to the environ- ment itself, which were related to the religion of Mormonism, a very repressed religion. Conservative and…