Purple Magazine

— F/W 2014 issue 22

Doug Aitken

Artist DOUG AITKEN designed his new house, which he calls ACID MODERNISM, in Venice, California like a geometric nest, an architectural artwork tuned into the coastal environment. Seismic microphones convey the tectonic sounds of the earth and ocean into the house; windows and mirrors bring the daylight deep inside its walls; tables and staircases can be played like instruments; flora merges from exterior to interior; organic and inorganic materials are carefully combined. it is a machine for living — and a model for environmental architecture.

photography by MAX FARAGO

text by JEFF RIAN

The artist Doug Aitken and his partner Gemma Ponsa built a house in the hills of Venice, California. Not just a house, it’s an art- work, a creation, a kinetic environment, a generator of experience, a projector of architectural possibility. One might think of Kurt Schwitters’s improvised Merzbau, pieced together over a 14-year period, but that was more like Cubism and nothing like Aitken’s envi- ronmental “futuretecture.”

The Aitken house is an architectural concept “physically connected to the vibrations of the surrounding nature” and designed to merge with the environment more profoundly than Frank Lloyd Wright’s environmental consciousness by delving deeper into materials and the location itself and by making Acid Modernism an ongoing home proj- ect. Plants bring the outside inside. The foundation was fitted with seismically sensitive microphones that amplify and transcribe into musical tones the earth rumbles and echoes of the nearby ocean. Music-making materials are integrated into the structure, with micro- phones in stairs that record ascending-descending tones, and play- able marimba tables made of stones, metal, and hollowed-out wood, which can be activated by hands, feet, or mallets. The house is also a light machine, with a kaleidoscope of mirrors in a staircase and prisms that reflect and convey sunlight to the interior. It has a nature-related graphical scheme, too, with leaf-like wallpaper patterns that spill onto the furniture. Mostly, though, it’s an optimistic artist’s private think- tank — a door is fitted with a bookshelf, its handle made like a copy of Joyce’s Ulysses — keyed to West Coast sunshine and the sounds of earth and waves. The house seems engendered by a philosophy of experience, a shrine for a communal religion based on life as lived, a kind of wonder drum to experience and enjoy the here and now.

Aitken was born in Redondo Beach, California in 1968, and graduated from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 1991. The word West might be psychically imbued into Aitken’s geographical sense of space and experience, a way of life that is more outside than inside, one that is faster, sunnier, and more casual and physically friendly than, say, life up north or on the humid East Coast. In fact, in 2010, for an exhibition (and a book) titled “The Idea of the West” at LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art, he asked a thousand people for their thoughts on the subject. But, more than that, ever since he emerged as a working artist, something more experiential than objective has marked his inter- ests; he wanted to push art toward active physical awareness, to create an art of experiences as well as appearance.

So-called Western civilization, with its hierarchical flow of history and information technologies, is the demiurge of a real historical move ever westward from Attica, Greece, and terminating at the Santa Monica Pier, at a place that would become the mecca of world enter- tainment, middle-class lifestyle, and cinema as art. Aitken grew up at the entertainment culture’s epicenter, where local experience created metaphors for the rest of the world to imagine and consider — much more than just the weather. But for his art, rather than making stable objects like photographs, sculptures, or paintings — or even videos with a beginning, middle, and end — he created artworks as function- ing environments that extend experience. Using varieties of media and materials — photography, printed materials, sound installations, constructed objects, indoor and outdoor projections that require moving around, moving vehicles like trains and barges, and numerous books on subjects like speed (I Am A Bullet: Scenes from an Accelerating Culture, 2000; Doug Aitken: A-Z Book [Fractals], 2003 and travel

(99 Cent Dreams, 2008) — he’s found ways to generate multisensory art experiences in which memories ricochet backward and forward. They aren’t simply objects or installations one looks at; they’re the- aters of experience.

Doug Aitken

Doug Aitken

Looking for subjects, Aitken has traveled to evocative cultural locations, such as South Africa, Jonestown, Guyana, and India’s Bollywood. In 1997, when Purple first presented his work, he based his Diamond Sea on the 40,000-square-mile Diamond Areas 1 and 2 in southwestern Africa — which have been sealed off by the diamond mining industry for over a century. In a darkened space, he set up a multiplex video projection and a large photo-transpar- ency of the heavily guarded desertscape wracked by industry. Music by Nine Inch Nails, Aphex Twin, and Gastr del Sol accompanied the presentation. Into the Sun, 1999, was a 24-hour film loop based on a recreated, raucous, Bollywood soundstage, complete with a floor of red. Hysteria, 1998-2000, replayed found footage of front-of-the- stage rock concert fans, the origins of the mosh pit. He’s created a number of video projections on the façades of, among other places, the Vienna Secession building (Glass Horizon, 2008); MoMA in New York City (Sleepwalkers, 2007); the circular Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. (Song 1, 2012), which used the song “I Only Have Eyes for You” for the wrap-around projection. He’s made a number of sound pieces that replay local sounds or sounds made in the ground in different locations. And then there was the traveling show, Station to Station, 2013, a performance involving musicians and international artists of every stripe, too numerous to mention, improvising on a train that made nine stops from New York City to San Francisco.

The great American practical philosopher John Dewey wrote in his lecture collection Art as Experience that “art is a quality that permeates experience; esthetic experience is a manifestation, a record and celebra- tion of the life of a civilization,” but “[oftentimes] … the experience had is inchoate … [and] not composed.” Experiences happen to us, often by chance, and aren’t always clear. Yet something “visible, audi- ble, or tangible” is felt. As philosopher Richard Rorty wrote, Dewey wanted to “shift attention from the eternal to the future,” from other- worldly metaphysics to the actual relationship between man and physi- cal experience, and philosophy without a Creator.

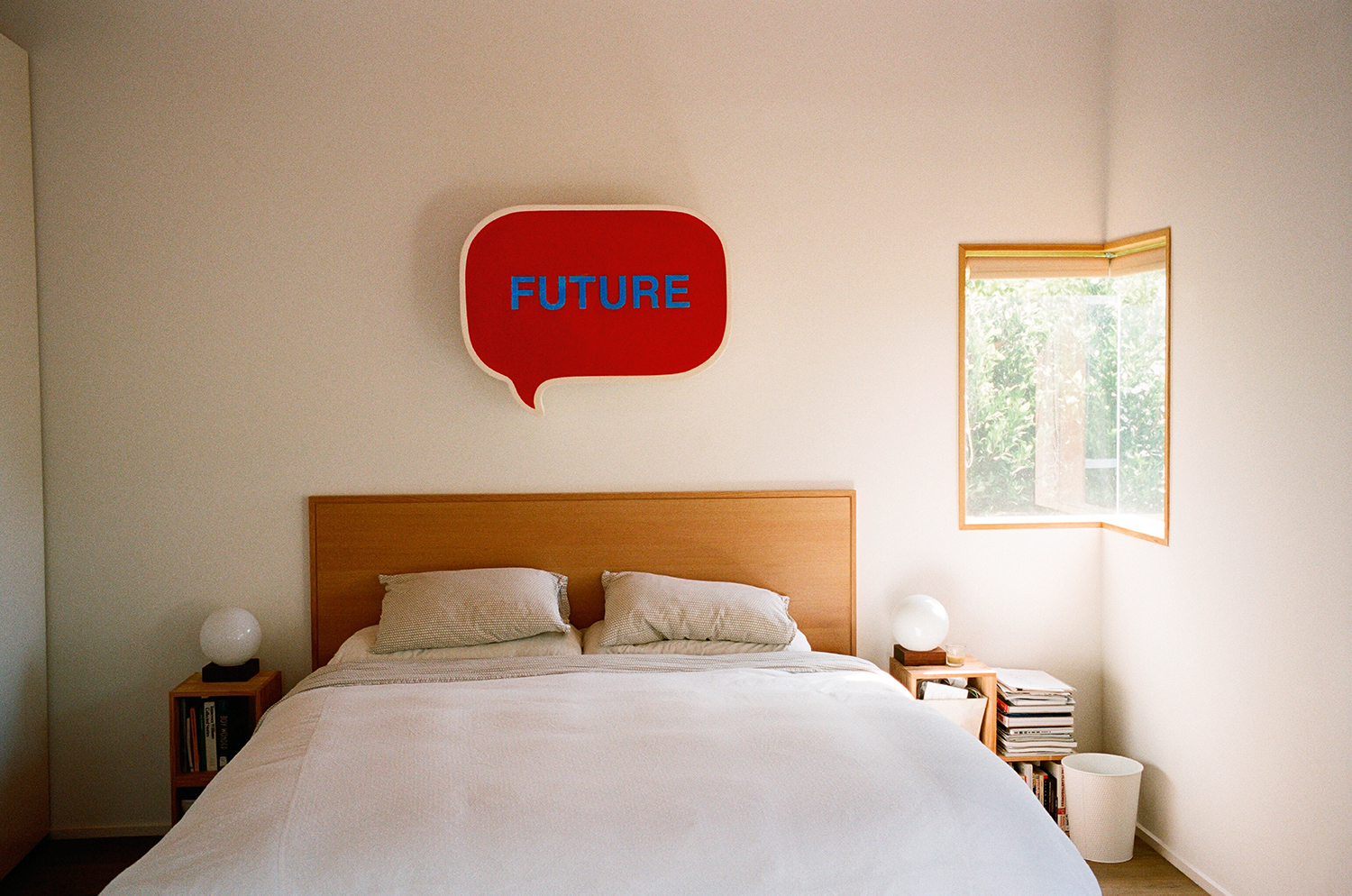

Doug Aitken, Future, 2012

Doug Aitken, Future, 2012

Aitken’s art is a manifestation of inchoate sensation. His work reflects his intuitions in varieties of forms, in real time and real space. Contemporary art’s current metaphysics, if one can use such a word, merges art-making with experiences that include music, film, performance, and architecture, but which also include the pro- prioceptive sensitivity of things, such as car racing, massage and yoga, sports, comedy, the escapism of alcohol and drugs, the exag- gerated if not drug-like projections of special-effects technologies, and the emotional sensations made possible by filmed or videotaped experiences (particularly as movie-going is replaced by download- ing). In this world, Plato’s Forms, the symbolism of Greek theater, and Freud’s dream psychology have given way to cognitive psychol- ogy, conscious processes, and images of Earth photographed from the moon. Art isn’t necessarily made anymore for one type of archi- tecture, but rather for any kind of space, including the screen of a smartphone. From that perspective, Earth, too, is an artwork, and we are its curators. That’s been a subject in art since the 1960s. Aitken gives us his take.

Marshall McLuhan described electronic communication as made up of literacy and the secondary orality of television, radio, and telephones, which now includes screen images and IT. Following such thinking, bodily awareness includes a hunter-gatherer’s space-time intuitions, a literate’s sense of historical narrative, and an engagement with sci- entific technology and the myriad projection of images. The result, according to McLuhan, was a complex mental mosaic, which created our multisensory physical and psychological profile.

This brings us back to Doug Aitken and Gemma Ponsa’s elegantly appointed Earth pod house project, plugged directly into the Mother Lode, taking her pulse, listening to her heart, attempting unitary inter- course. A career made from intuitions that lead him ever outward allowed Aitken, 20-something years later, to think centrally, to conceive his home like a think tank. An environmental awareness, inside and out, created a live-in art experience.

The world was made smaller and more visible by space-age technology. Earth is a massive toolbox of resources and projections, in McLuhan’s parlance, an extension of minds and bodies. James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis declared Earth’s atmosphere a docile organ coextensive with life. We made it what it is now. This is reality physics — glorious from afar, scary in detail.

When Doug Aitken was making Diamond Sea, the novelist J.G. Ballard’s otherworldly descriptions of the space-age industry’s futuristic sub- urbia came to mind. Doug seemed to be searching for an alternative aesthetic experience, which wasn’t all that clear to me. Since then, one might think he’s sought ways to make human insanity aesthet- ically manageable. This would be a good thing, and a way to start, at least for literate caretakers.

Artists have always addressed the limits of human experience. Hieronymus Bosch depicted the horrors of Hell as a warning to heed religious dogma. Such madness continues where there is no art. Doug Aitken’s art is an optimistic antidote. Moral and ethical issues are implied indirectly. He looks for experiential beauty, life as experience as art. Few of us will ever have such a house as his, but we could endeavor to have art permeate experience. That would be something.

END