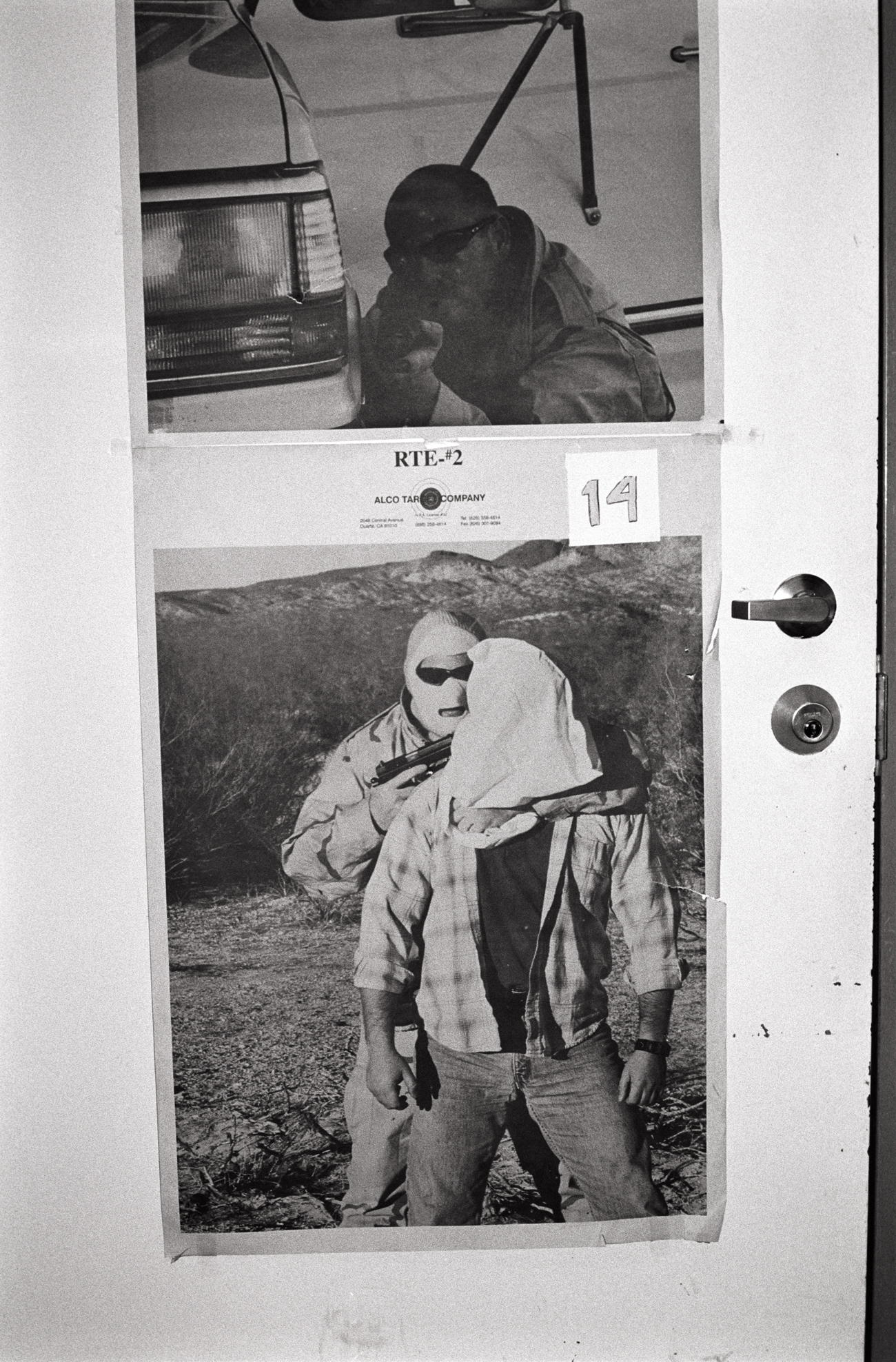

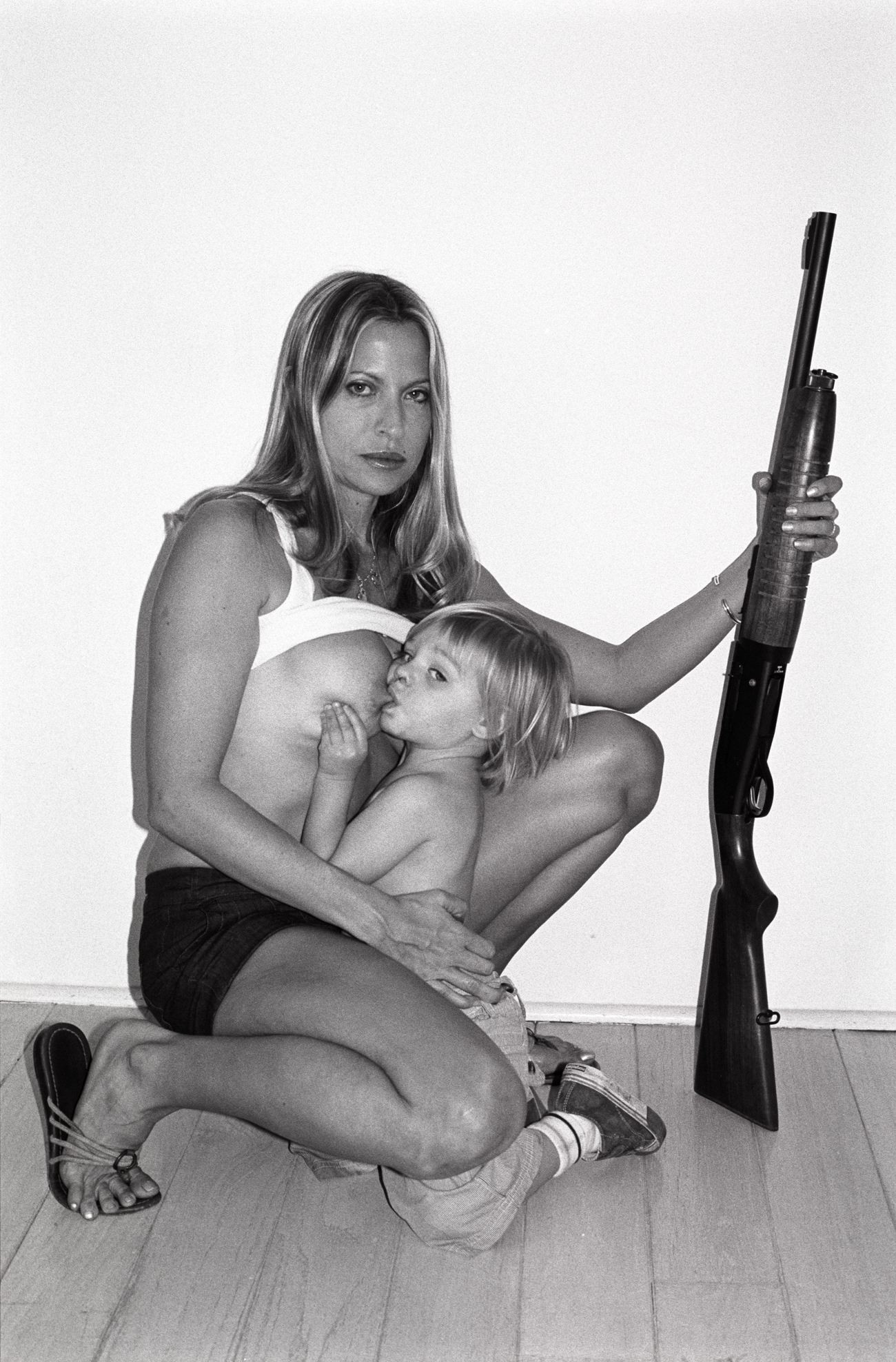

Purple Magazine

— F/W 2008 issue 10

Los Angeles

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photo Terry Richardson

photographs by TERRY RICHARDSON

text by JEFF RIAN

World’s End

Where the sun sets on WESTERN CIVILIZATION and all the migration and immigration stops. Period.

It’s a dream and a hedonistic parody of PLATO’S REPUBLIC, with its New Age mystics and psychic murderers, Hollywood movies, custom cars, the AKERS, and SCIENTOLOGY, organic groceries, aesthetic surgery, piercings and tattoos, STREET GANGS, Mexican migration, the HIPPIE…