Purple Magazine

— F/W 2008 issue 10

Camilla Nickerson, Mario Sorrenti, Lou Doillon

Mario Sorrenti

Mario Sorrenti

An entire section devoted to personal identity — photographed by MARIO SORRENTI, featuring family pictures, vacation pictures, still lifes, tableaux vivants, a fashion shoot, erotic pictures, a bit of cross-dressing, naked self-portraits on sets of advertising sessions, and one with a cell phone.

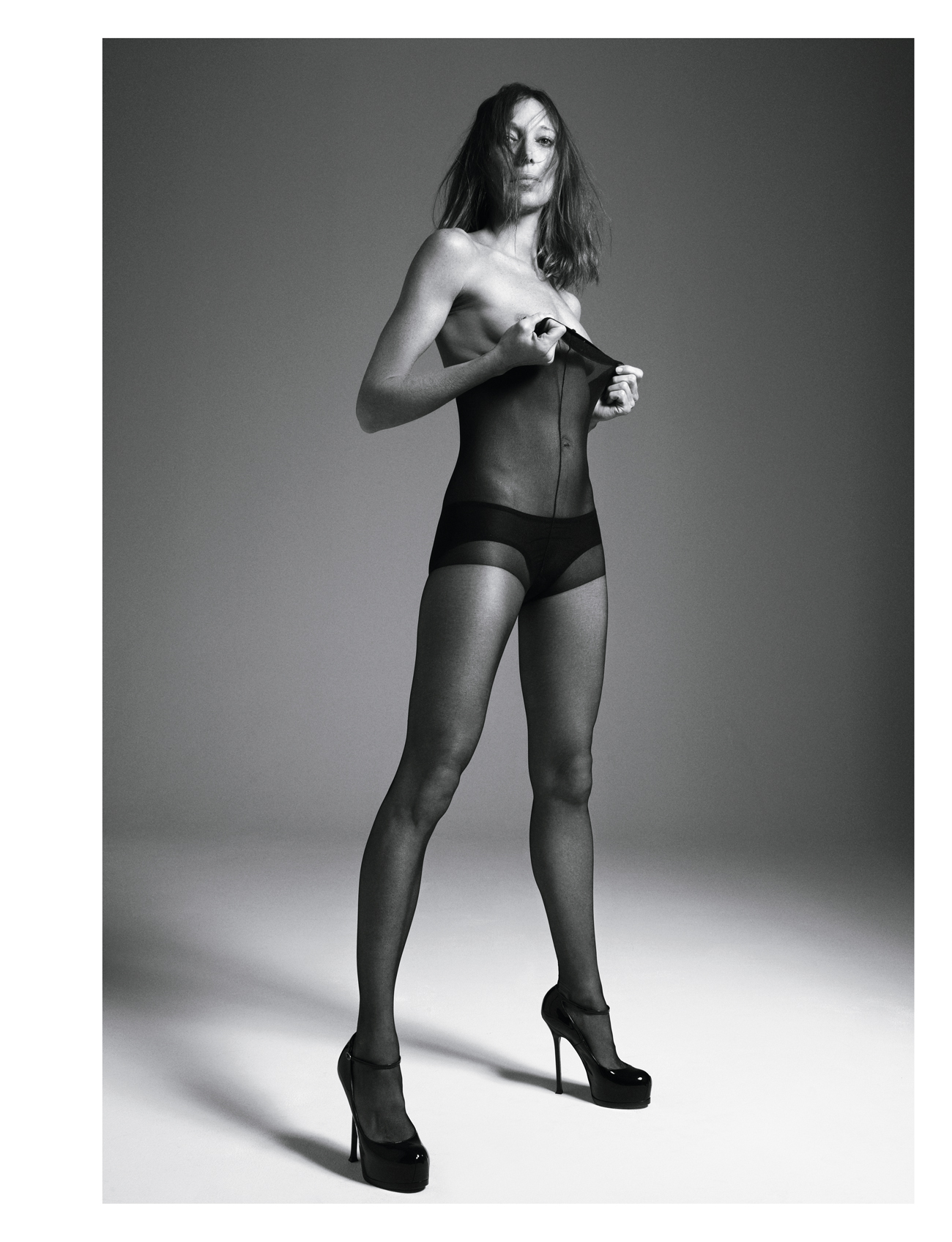

portrait #1 CAMILLA NICKERSON

photographed by MARIO SORRENTI

self-styled by CAMILLA NICKERSON

Camilla wears black tights with seam JONATHAN ASTON, black underwear AMERICAN APPAREL<br />and black patent pumps with strap YVES SAINT LAURENT

Camilla wears black tights with seam JONATHAN ASTON, black underwear AMERICAN APPAREL<br />and black patent pumps with strap YVES SAINT LAURENT

portrait #2 the self portraits of MARIO SORRENTI

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

OLIVIER ZAHM — You just got back from Japan. Did you enjoy your trip?

MARIO SORRENTI — I loved it. I took pictures day and night.

Camilla wears a black-and-white knit top and skirt RODARTE, black spiky heels CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN and black stockings WOLFORD

Camilla wears a black-and-white knit top and skirt RODARTE, black spiky heels CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN and black stockings WOLFORD

OLIVIER…