Purple Magazine

— S/S 2015 issue 23

Gabriel Orozco

portrait by Magnus Unnar

portrait by Magnus Unnar

man, play, and games

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM and ALEXIS DAHAN

portrait by MAGNUS UNNAR

All works are courtesy of the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris and Kurimanzutto, Mexico

Gabriel Orozco is a traveler, an artist inspired by materials and opportunity. Born in Mexico in 1962 to an artist, the product of a leftist society, he was sent to alternative schools, and his life began, like the lives of many kids, with chess playing and soccer. He began by walking, thinking, noticing, traveling (he and his father are francophiles). He lives in Mexico and New York City — taking pictures and making uncommon objects out of clay and terracotta, such as his hands for My Hands Are My Heart (1991). He narrowed the entire cross-section of a Citroën DS, for his seminal La DS (1993). He calculated geometrical paintings in red, blue, white, and gold for Samurai Tree Paintings, based on interrelated circles, like the fabled swordsmen twirling steel. He’s reconceived boomerangs, soccer balls, ping-pong tables, bicycles, and has carefully collected and organized desert samples, rubbish, and things so seemingly disparate as to make him an avatar of whatever it is you want to call contemporary art. He’s all of that, as if by accident, himself.

OLIVIER ZAHM – What was your childhood like in Mexico in the ’70s? I just discovered that your father was an important painter.

GABRIEL OROZCO — It was a very nice childhood. I was born in ’62, so it was full of left-wing people, artists; my father was a young painter teaching at the university in Veracruz. I was surrounded by politics, the ’68 student movement, there as much as in France. My childhood environment was very artistic, full of photographers, artists, singers, music. My schools were like Montessori, so it was a very progressive education. My father was important, but not the famous Orozco, who was another generation and unrelated to us. But my father also painted murals and was politically active in the Communist party. That was my childhood.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The ’70s was an important moment in art, with greater freedom.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes. On one hand, there was total freedom, abstraction, the women’s liberation and hippie movements. On the other were movements that were not so much into abstraction but more Marxist and political. You remember the discussions about realism and figuration, for and against abstraction — the polemics against US imperialism were very important in the ’60s and the ’70s.

ALEXIS DAHAN — Was it forbidden to speak English at home?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Well, in my house, my father didn’t allow it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That’s incredible.

GABRIEL OROZCO — We wanted to be independent from the US.

ALEXIS DAHAN — Was that one of the reasons you transformed the Marian Goodman Gallery into a Spanish school for your 2013 exhibition, “Spanish Lessons”?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes. A lot of my work comes from my childhood. In this project I was asking the public to learn another way of communicating and also to see language as an art form. So I organized conferences and readings in Spanish about Jorge Luis Borges. They could listen to Borges even if they did not understand it. I thought that was important. There are so many Spanish speaking people in the US, especially in New York. Nobody makes the effort to learn the language. I wanted people to experience otherness through art.

ALEXIS DAHAN — When did you first aspire to be an artist?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Since childhood — since the beginning. I saw my father painting every day, and he was happy working. He loved to work. And also the environment of art-making was nice. He knew writers and musicians and filmmakers. I simply liked the idea of painting and drawing. I also wanted to be a Formula One race-car driver because I learned to drive very early. But in Mexico it was a bit hard to be that. We have hardly anything, and nothing like Formula One.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do those early interests still influence you?

GABRIEL OROZCO — For sure. I still like fast cars and soccer. I’ve played soccer my whole life. A lot of my art comes from my childhood. Even mathematics and geometry, because I didn’t have the classic teaching of mathematics and algebra. It wasn’t about memory, it was more…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Poetic?

GABRIEL OROZCO — It was more visceral.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s a strong geometric element in abstract South American art, particulary in Brazil. Was it like that in Mexico?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes. It was important in Mexico, too. But the South Americans are more famous, say in Venezuela or Argentina. Mexico in the ’60s and ’70s was not completely devoted to abstraction. It was still connected to muralism, and that’s the art I grew up with: figurative painting, political art.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The idea that art is a form of popular education?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes, with content. With history. And abstractionism was…

ALEXIS DAHAN — More bourgeois?

GABRIEL OROZCO — More corporate American, in a school-of-economics way. It was a bit more evasive, formalistic. So there were the two oppositions in Latin America. But in France, you have a lot of abstraction that is connected to politics. And a lot of the art in Mexico was connected to Europe, particularly ’60s French politics, which was much closer to us than the Americans.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In France, the influence of the American art critic Clement Greenberg pushed formalism and minimalism in French art, creating its own language outside of consumerism. But we also had Guy Debord saying art had to be political, on the street. He wanted to change the way people looked at movies, at advertising, at everything. Greenberg came from America, and Guy Debord… Even Daniel Buren was not really formal at the beginning. Artists wanted to change perception.

ALEXIS DAHAN — Along with getting out of the studio, as Buren did, which is probably something you relate to.

GABRIEL OROZCO — When I started to get bored in my studio, I looked at options. I went out, did this and that, started to look at Land art, at Robert Smithson’s idea of landscape and public art. In the streets, Impressionism is important, the flaneur, the walking around, the idea of the individual in the urban landscape. I could react to reality without using tools; I could work outside but not have to bring anything with me, the way the Impressionists brought their paints.

ALEXIS DAHAN — What kind of tools?

GABRIEL OROZCO — I was using a camera as a way of documenting what I did. Sometimes the photo didn’t capture what actually happened because sometimes photography is not enough.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How old were you when you did that?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Well, when I finished school, in ’84 or ’85, I was 22 and didn’t want to do postgraduate studies, so I went to Europe. I was interested in Madrid because at that time, I had a close friend living there from my school who told me I had to come. I arrived in ’85, ’86 in Madrid, with no money, so I was actually not so much into the big party, La Movida Madrileña. I was more of an underground South American, and they were still very classist. It’s a very classist society, even still. But it was a very formative moment because although I didn’t connect with the art of the Spanish Movida Madrileña, I learned from other artists in the world…

OLIVIER ZAHM — La Movida was the best time in Madrid.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Best time ever, exactly. A crazy time. Madrid was very happy, a lot of things happening. At that time, it looked like it was going to be forever.

ALEXIS DAHAN — What were you doing there?

GABRIEL OROZCO — I started to look at books of Arte Povera and British sculpture from the ’80s and Robert Smithson and John Cage. I read a lot about John Cage.

View of the inside of the French studio where the Samurai trees were produced as observed on p.196 of the MoMa retrospective catalog

View of the inside of the French studio where the Samurai trees were produced as observed on p.196 of the MoMa retrospective catalog

ALEXIS DAHAN — Did anything specifically about Cage interest you?

GABRIEL OROZCO — I read a nice little biography about Cage’s early years, which was very important to me. It was my first understanding of a way of working that used chance operations, that accepted noise, accident, and reality in a very different way from so many other artists. Although I was not into music or even poetry, really, I tried to make accidents in my life in terms of not controlling — academically — the processes, and trying to generate processes that lead to other options, solutions, or resolutions. So to be in Europe was important to me. I also traveled to Italy and briefly to Paris. It was also important for me to be alone and to be exposed to the situation of not having a studio and forced to work and do things outside.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you survive in Madrid, at the age of 22 or 23?

GABRIEL OROZCO — After I finished school in Mexico, I did a show of my student paintings. I was not such a bad painter. I won two prizes in Mexico, one for drawing and one for painting, and people bought my works. If you see them, they are very different from what I do now. But there were some good ones. Also I had some savings, which would cover about six months, and then when I was in Europe, I sold a couple of pieces to survive. But I was living on very little money. At that time, it was easier.

ALEXIS DAHAN — You didn’t have to get a job?

GABRIEL OROZCO — No, I never had a job — never in my life. I never had money from my parents, either, so I always managed.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You lived solely from your art?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yeah. Since school. I’ve been lucky, and maybe people liked what I was doing, and they were supportive enough to buy etchings.

OLIVIER ZAHM — From a very young age, were you conscious of your talent?

GABRIEL OROZCO — That’s a good question. I think I’ve known since I was a kid that I was not stupid and that my brain was fast. For example, I play chess and won a championship in Mexico. I was sub-champion of my category when I was a kid.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Plus you were quite handsome.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Well, I never thought about it. I was surrounded by very, very beautiful people. All my friends were better-looking than me. The girls were very pretty. But I didn’t have girlfriends until I was in high school because I was concentrating on soccer, chess, and things like that. I never considered myself handsome at all.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So you never played the role of the handsome artist?

GABRIEL OROZCO — No, never. Over time I discovered that girls were in love with me, but I never knew. Now, 20 or 30 years later, I realize I wasted a lot of time playing soccer. But from what people tell me, I was charming as a boy, friendly, healthy in general, and maybe for that a lot of people liked and supported me. At the same time, when I was in school, there were other painters who were better than me. I remember a couple of friends whose drawings were beautiful and precise. Even my father, when he was a student, he was a superior craftsman. His drawings were amazing. I can draw, but I could see in the school that I had something else in my work that was expressive, and people were connecting to it, but in academic terms, or in craft, I wasn’t a virtuoso. But my ideas and the way I put art together, synthetically, solving problems, were very sober and accurate, and the work was expressive, which, I think, engaged people early on.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, early on you discovered the language of contemporary art.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yeah, I think around 24.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You mentioned Smithson, Cage. What about Piero Manzoni?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes, Manzoni came a little later.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And Gordon Matta-Clark. Was his work a total change of perspective?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Information at that time didn’t circulate the way it does today. In Mexico, we didn’t even have an art magazine. The Spanish-speaking world didn’t have magazines to connect with the world until the ’80s. Before that Spanish people were isolated from the American and English-speaking or French worlds. The information I got when in school was limited to classical art and traditional things.

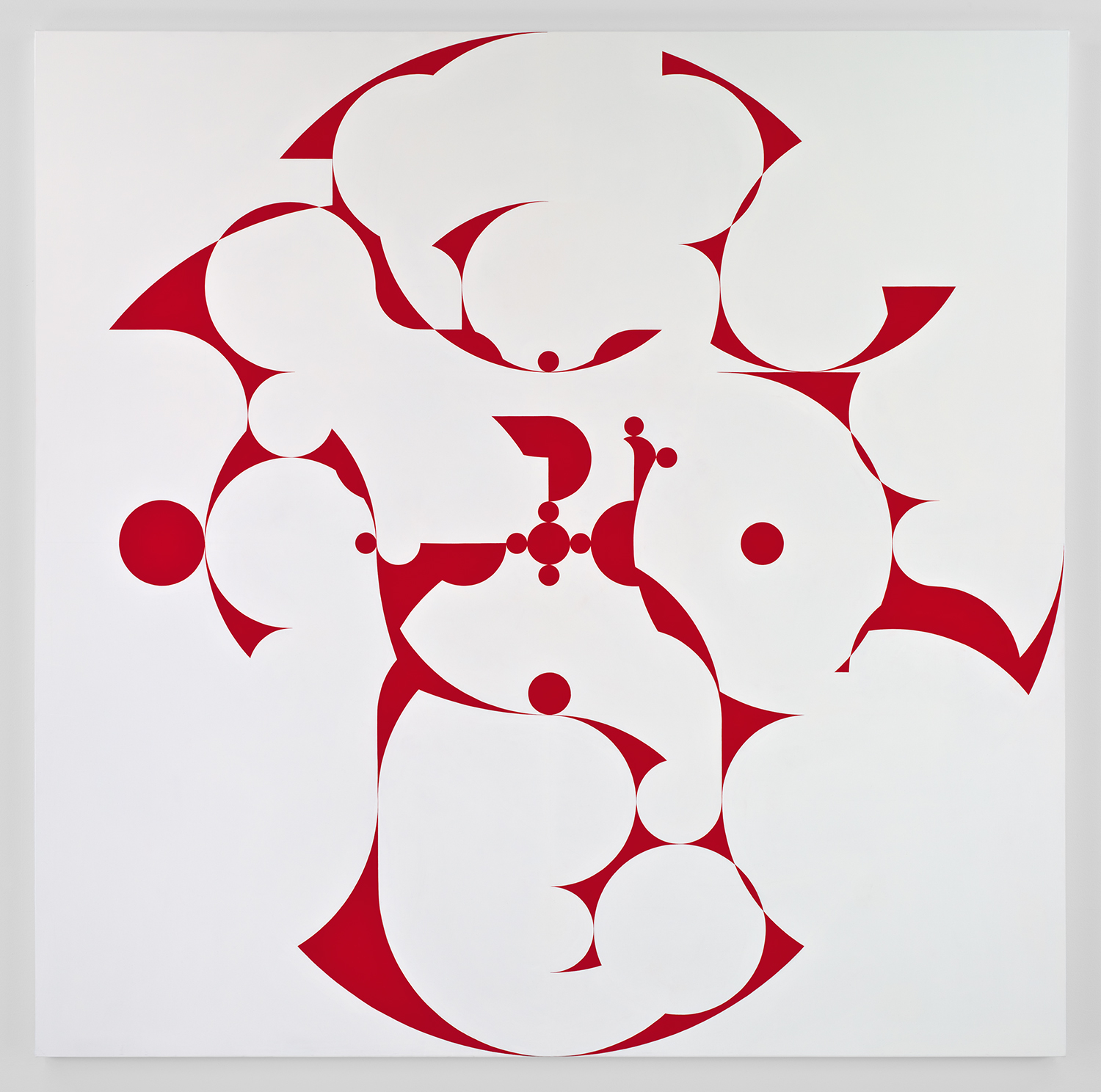

Kytes Tree, 2005, synthetic polymer paint on canvas

Kytes Tree, 2005, synthetic polymer paint on canvas

ALEXIS DAHAN — Did that change in Madrid?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Madrid was changing, opening up. They translated many more books, and artists such as Tony Cragg and Richard Long were being invited from the UK. I saw their exhibitions. Also, the Arte Povera people started showing in Madrid. That was like a waterfall for me, a Niagara Falls of information. I was hungry for information, and I tell you, my brain was fast. I was reading books on chess and learning about artists. That happened in a year or two. I was able to assimilate and also connect my life to the necessities of the moment.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why did you escape from the traditionnal work in a studio?

GABRIEL OROZCO — I didn’t want to be in a studio, painting. It was existential, a necessity. It’s not so much that you adapt to the time, but the time gets adapted to you. You start to circulate in the world, and the world starts to circulate in you. Then you’re part of the wave, like surfing; looking at the waves, and you need to reach one. Which one is the right wave for you to catch? That moment for me was in Spain. After that, around ’86 or ’87, I came home to Mexico. And in Mexico, my work was really different from Mexican art. In ’87, I started to work in the streets. I was very alone there. Then photography became very important because many of my friends were photographers. I didn’t have a camera; I borrowed them. Then snap cameras came out, a hundred dollars. It became cheaper.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Pocket cameras changed your life.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Completely. I could go to dangerous areas in Mexico City and take photos. I could travel.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Were you working alone or alongside friends?

GABRIEL OROZCO — A group of artists who were younger than me became interested in what I was doing, and they started coming to my house. We made a workshop, starting in ’87. We made a kind of school. Not so much a collective because they were younger, still developing, not ready; so we studied art, in my house, for five years.

ALEXIS DAHAN — Did they look up to you?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes. They wanted to learn from me. They wanted to know what I knew. They wanted to sneak into my books. They wanted to get some beer. They were very charming.

Red Roots, 2008, tempera on canvas

Red Roots, 2008, tempera on canvas

OLIVIER ZAHM — You created a sort of alternative school?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes, by accident I became a teacher very early because they asked me to do it. They came on Fridays. Some days they’d arrive at 10 in the morning and spend the whole day with me, and other times friends came in the afternoon.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What was the effect of the earthquake in ’85 in Mexico?

GABRIEL OROZCO — It was very strong. I was there. My house was not affected because we were living outside the city. We felt it, though. It was at seven in the morning. I was shaking, and then I fell asleep again because in Mexico we regularly have these things. And then at nine I woke up.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you discover the disaster on television?

GABRIEL OROZCO — No. I woke up and started to do my drawing — it was an elaborate drawing — and around 9:30 or 10 I turned on the radio to hear music, and that’s when I realized there’s no music. Everything was happening: dead people, ambulances, everything collapsed, the TV and the radio, but they managed to put together information, like in a war. That’s when I realized the city was destroyed. I went out and started to help people and organize with friends, finding out who was okay. For two or three weeks, we helped people and organized things, but the notion of the city became one of fragile public areas. It’s a monstrous city; only suddenly, it became like a little village, damaged but friendly. The idea of public space, the street, the anonymity of the big urban circulation became something else: a much more intimate connection with the city.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Were you conscious of the fact that, coming from Mexico, you had to fight for recognition? As if you came from a different perspective, with a different sensibility, to find an art world, especially at that time, that was mostly concentrated in New York, London, Paris, and maybe also in Italy and Germany. But basically the art world was very northern. Were you motivated to express something more Latin American?

GABRIEL OROZCO — No, because in Mexico the problem I was fighting was nationalism. Mexico was very strong in neo-Mexicanism, which was a kind of postmodern Mexican style, very kitschy, with a lot of painters using Mexican motifs. But it was like that all over the world.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So in the ’80s you were reacting against national expressionism?

GABRIEL OROZCO — I was against any kind of nationalism, kitsch, stereotypes of America, Paris, London, and all that. So what I tried to do with my work was exactly not to act like a Mexican, saying “Viva las enchiladas!” I started to behave a little bit like a chess player, which is neither Mexican style nor American style. I was trying, in a way, to erase myself.

ALEXIS DAHAN — Did your Mexican friends criticize you for that?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes. Even in Mexico, many people criticized me because I didn’t want to be seen solely as a Mexican artist. My work was international or whatever. Only now that I’m older, you can say there are Mexican aspects in my work.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’re not expressing something specifically Mexican, but maybe from outside Mexico you’re able to create an approach that synthesizes different influences. You mentioned geometry, conceptual gestures, and chess, which is reminiscent of Duchamp. Then there’s the more political art, oriented toward nature, the landscape, and even, say, the Situationists: the way you approach the street captures its poetic details. This very synthetic approach is quite unique. It’s not specifically Mexican, but maybe your position outside gives you the possibility to embrace such different influences, which maybe a British artist, a German artist, an American artist, couldn’t embrace…

GABRIEL OROZCO — Well, what I think is that every good artist is a combination of things. For me, there was a kind of triangulation between Mexico, Europe, and New York. I started to live here in New York in 1991. I was traveling a lot. I wasn’t interested in staying here. People started to talk to me as if I was a New York artist. They started to do shows about New York, and they wanted to invite me, but I refused. I didn’t like to be considered a New York artist. I kept my passport. I am Mexican. I’m not an American citizen or anything like that. I am a traveler. And I was always very much in touch with France, with Paris. My father was also a big fan of Paris. I traveled there when I was a kid and have loved it since then.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Since Alexis and I are French, there’s pressure! We question our love for Paris.

GABRIEL OROZCO — That’s part of the love, no?

Kytes Tree, 2005, synthetic polymer paint on canvas

Kytes Tree, 2005, synthetic polymer paint on canvas

OLIVIER ZAHM — Yes.

GABRIEL OROZCO — I know, I know. And now they made me an Officier des Arts [an award from the French government for eminent artists]. I was very happy about it. Which is not important for French people, but when you’re going there and all that, it’s a nice gesture.

ALEXIS DAHAN — You’re talking about some kind of cosmopolitanism in art, not just of culture or language, but of art and different movements.

GABRIEL OROZCO — What’s also interesting is that when you come from a powerful country, you can impose your mythology. You can talk about Mickey Mouse, and it looks important because it’s from America, and everybody listens. If I were to take folkloric or idiosyncratic elements of Mexican culture, it would look folkloric. But I was always — and many artists, like John Cage, have been — influenced by other spiritual movements, like Buddhism for example. Cage was influenced by Buddhism, philosophically speaking. I, too, was interested early on in Buddhism and also in Indian art. So my range of influences is very eclectic.

OLIVIER ZAHM — This is a powerful position because you don’t come from a powerful country in terms of economics or politics or international influence. But what you have in Mexico is an amazing landscape, two seas, a climate that attracts people. You also bring this geography into your art in the way you deal with materials, such as food and clay.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yeah, material, a lot of materials. I was in France when I started to use clay. Maybe people say when I started to use clay, for example, that it was very Mexican, and I said, “clay?” It’s Chinese, first of all, and the most important ceramics today are French or American, not Mexican. There are many preconceptions of what material is. If you think marble, you think Italy, and I guess if you think clay, you think Mexico — wine is France? I don’t know — is that a material?

OLIVIER ZAHM — It could be with you!

GABRIEL OROZCO — There are many clichés about it. During the ’90s, it was almost like a mission to make New York as powerful as Paris or London — it was very important to me to decentralize New York. When the ’90s came, and I was here and my work started to have some weight in New York, and maybe at the same time in Paris for me it was very important to generate a decentralization of the powers, at least psychologically.

Asterisms, 2012, installation view, Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin

Asterisms, 2012, installation view, Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin

OLIVIER ZAHM — Can we speak a little bit about your interest in games? You’ve done a lot of work with games, ping-pong, chess…

GABRIEL OROZCO — And boomerangs. My last show is boomerangs.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where does this interest in games come from? For me, it’s very connected to the Surrealists, like Breton, Leiris, Caillois, etc.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes, of course.

OLIVIER ZAHM — They were fascinated by games as a form between fantasy and reality. You enter a world that is also changing the rules. Are games, or the boomerang, a metaphor?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Since I was a kid, I’ve loved to invent games. I liked chess and soccer, so I like teamwork. I like the ball. I like the idea of doing something with a very simple object. I was never much into jogging or solitary sports.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You like interaction.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Exchange and interaction. When I started to do my walks outside and then to move objects, I began to think a bit like a chess player, inventing a game with found situations. It’s when you invent a ping-pong table, or you invent a game with socks or something, that it generates a position similar to a child trying to spend time in a different way using everyday life. I was also interested in how games and sports are a reflection of space and time in every culture. Every sport reflects what the culture is: how they conceive of the landscape, of time. That’s why it’s impossible to play cricket today. It’s a game from the 18th, 19th centuries and its sense of time. Baseball is closer to us, even though it’s also kind of slow. Basketball is faster. But if you see the evolution of sports and different board games like chess or Monopoly, every game and every sport represents the culture that invents it.

ALEXIS DAHAN — You explore and change the form of the games.

GABRIEL OROZCO — I change the memory of the game. So if you know how to play ping-pong and you come to the ping-pong table I did, your body will do movements that you remember, but this is not the same. You have to be slower, or higher, because the whole poetics of the game changes, and the body memory changes with that and has to adapt to a new set of rules.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, does an artist have to change the rules of a game?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yeah, I think so. An artist has to change the rules. Or invent the game.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you think that there’s always a possibility to change the rules, to create new rules? To not accept rules?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So in a way, you’re still a political artist.

GABRIEL OROZCO — I hope so.

Accelerated Footballs, 2005, one hundred sixty-five modified soccer balls

Accelerated Footballs, 2005, one hundred sixty-five modified soccer balls

OLIVIER ZAHM — Political art is very rare these days — the politics of form, of images.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Even the politics of protest. We grew up with a lot of political art that was about demonstrations, messages, pamphlets, which are still very important activities, but my work is not like that. My work is not about that.

ALEXIS DAHAN — What is it about?

GABRIEL OROZCO — It’s about changing the way you think. Making the rules more complex, which I think is stronger than just protesting or denouncing.

LIVIER ZAHM — Your work defies today’s super-expensive and more decorative art product.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Well, yes. It’s more and more like that as a cultural symbol of powerful countries, where you have the infrastructure and museums and spaces and the market…

OLIVIER ZAHM — And the collectors?

GABRIEL OROZCO — And the collectors, too. It’s almost like Disneyland — all the spectacle.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But it’s like that in China, too.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yeah, because it’s related to nationalism. You know the great American invention is publicity. That is the art form that Americans really created. The first was Warhol, and then all the rest is publicity. You need money to do that, and now, with publicity, you can be president. You don’t need to be a politician. You really just need a good PR company, and you can be president.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You speak about gesture, and you have this sentence: “A simple gesture can be art or not.” So when, for you, would it be art?

GABRIEL OROZCO — I also like to say that a very small gesture can be very powerful. I think it’s art when it’s received and has some impact on the landscape and on the public. A small gesture can move the eye of someone who suddenly smiles or move the eye and suddenly, boom, someone gets the message, and it’s just amazing. I think that is an art: how to move, how to communicate through your body. Small gestures can be very powerful. And you know many people are very good at that. The same with art, it can be a very simple thing and generate a lot of impact in people. Sometimes you see amazingly big, very expensive sculptures, but they don’t generate so much emotion. They’re just big.

My Hands Are My Heart, 1991, two silver dye bleach prints

My Hands Are My Heart, 1991, two silver dye bleach prints

OLIVIER ZAHM — Because there’s no gesture?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Probably because it has erased the process and the possibility of accident. And it has erased the body that makes the work. So it’s alienated labor; it’s a product of an industrial capitalist factory in which you completely erase the history of the piece.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So the body is still important for you.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Very.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What’s the most beautiful piece you think you ever made?

GABRIEL OROZCO — As a piece? I think My Hands Are My Heart, the one with the clay.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Ah yes. It’s just a simple gesture.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yeah, very simple, very common material. It was ’91. It’s just a strong, simple, basic gesture, but suddenly it’s many things — it’s symmetrical; there’s gravity, but it’s floating; then there’s the body, but it’s the negative space of the body.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It could be a Miró, prehistoric, or a child.

GABRIEL OROZCO — It could be from any country, I think.

ALEXIS DAHAN — So you make all these simple, poetic gestures. You create new games; you change landscapes. At the same time, since about 2004, you’ve developed a parallel practice of painting and drawing the Samurai Tree. How do you make those?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Going back to my childhood, when I was talking earlier about mathematics, I was interested in conjunctions and intersections and the idea of the circle and spaces that interconnect. I also love biology. I love the idea of cellular atomic connection and construction. Since I was a kid, if you see my drawings, there were a lot of circles and dots, very atomic. But at the same time, there was an awareness of the perspective: horizon, verticality, and gravity. But then, I didn’t want it to be optical. So, I have a set of rules for how the colors are divided in four fields. I decided the colors would always be the same and jump like the knight in chess, so the circle grows by half or the double and always from the center of the field, and starts to expand to the limit. And then when you have it on the wall, you can see verticality, gravity, horizontality, and then different weights and fields. So you can have a possible landscape, a possible machine, a possible tree, a possible board game.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Or a possible jewelry.

GABRIEL OROZCO — A possible something that is very precise, but at the same time organic and kind of atomic but also like a plant.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s your visual system.

GABRIEL OROZCO — I think it’s my system, and it’s a little bit obscure and a little bit exotic for the history of abstraction…

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s also beautifully decorative.

GABRIEL OROZCO — It’s also kind of silly, and that’s why it looks a little frivolous and, therefore, kind of decorative. But the funny thing is, behind it all is a set of rules.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why did you call it Samurai Tree? That’s very confusing.

GABRIEL OROZCO — It is very confusing. The idea of the samurai is that after you think a lot, you make a decision, and you have to follow that decision because you cannot hesitate in the middle of battle. If you do change your mind, you’re dead. So, I applied that to making decisions about painting, which is full of little decisions — this color here is very boring, so I’ll take one decision, and then the tree is there because in my work there is a center point that starts to have ramifications…

OLIVIER ZAHM — So “samurai” is the strategy, and “tree” is the organic.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Something like that.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you’re doing it with stones, too.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Some stones, yes, because the idea of time and erosion is important in my work. I love stones around rivers because they erode and take shape. So much time is contained there.

ALEXIS DAHAN — So for 30 years, these themes have been recurring.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Absolutely. Very organically.

OLIVIER ZAHM — We didn’t speak about Duchamp because no one speaks about Duchamp now, but in the ’90s he was a big name in the art world. Now he’s sort of faded as a reference.

GABRIEL OROZCO — I don’t think he’s disappeared really. He’s a bit like Borges for me. Every time I read his interviews, it’s always very refreshing or stimulating for the brain, but he’s not an artist that you will go and try to copy. That is impossible in a way because his works are all so different from each other and they are very specific. And the motifs of each work are very different. And even the sexuality of each work is in a very different sublimation system, and one that you cannot try to copy or emulate. It’s a kind of system that was very particular in every work. And yes, there are works that are very useful for the thinking process of every artist in the world. Obviously the Readymade idea is extremely important. But he is an artist that is still mysterious. Still, not everybody understands him, not even the French.

ALEXIS DAHAN — Especially the French.

OLIVIER ZAHM — No, but the thing is his wordplay, his irony, is incredible.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Right.

My Hands Are My Heart, 1991, two silver dye bleach prints

My Hands Are My Heart, 1991, two silver dye bleach prints

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s a superior mind.

GABRIEL OROZCO — But a very French artist. It’s amazing how he was here in New York for a long time, but his titles remained in French. The play on words is in French. He’s super-French. Almost folkloric in a way. He’s very intellectual, but in a way also very street.

ALEXIS DAHAN — Do you associate yourself with being both intellectual and street?

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes. I’m intellectual because my life is like that, and I enjoy high levels of philosophy and reading and all that, and then the street-level, gang-style, trashy everyday life is very important for me, as well.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Would you say that your generation of artists, starting in the early ’90s, was the last of the avant-garde in the political or experimental sense? Do you still believe in this idea of an avant-garde?

GABRIEL OROZCO — What a question! I think, yes. I still do believe in the avant-garde. I think it happens all the time, and there are moments that are more visible because the world for some reason is more transparent. You can see it better because it’s not so foggy or full of dust from the bomb, not so permeated by interest in money. So I wouldn’t say the ’90s were the last avant-garde unless you are saying in terms of the 20th century. Then yes, you could say it’s the last one, but also the last as the old idea of a group of artists that were obviously in the forefront.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Pushing the limit of art.

GABRIEL OROZCO — Yes, so my generation was also international and wasn’t located in one city. And it was using the infrastructure that was growing at that point and pushing the limits of behavior, exhibitions, and communication, etc., of interaction. And in that sense it was an avant-garde. Everybody was looking at us — what would we do with that? It was influencing filmmakers as much as magazines and advertising. And then the market came, and a lot of things changed. After 9/11, the world turned out to be much more…

OLIVIER ZAHM — The world is more roduct-oriented?

GABRIEL OROZCO — The world is also just foggier, noisier, and trickier. It’s very hard to see. And for an artist who has avant-garde ideas today, it’s really hard to really be visible. There are many fake avant-garde

things.

END