Purple Magazine

— S/S 2015 issue 23

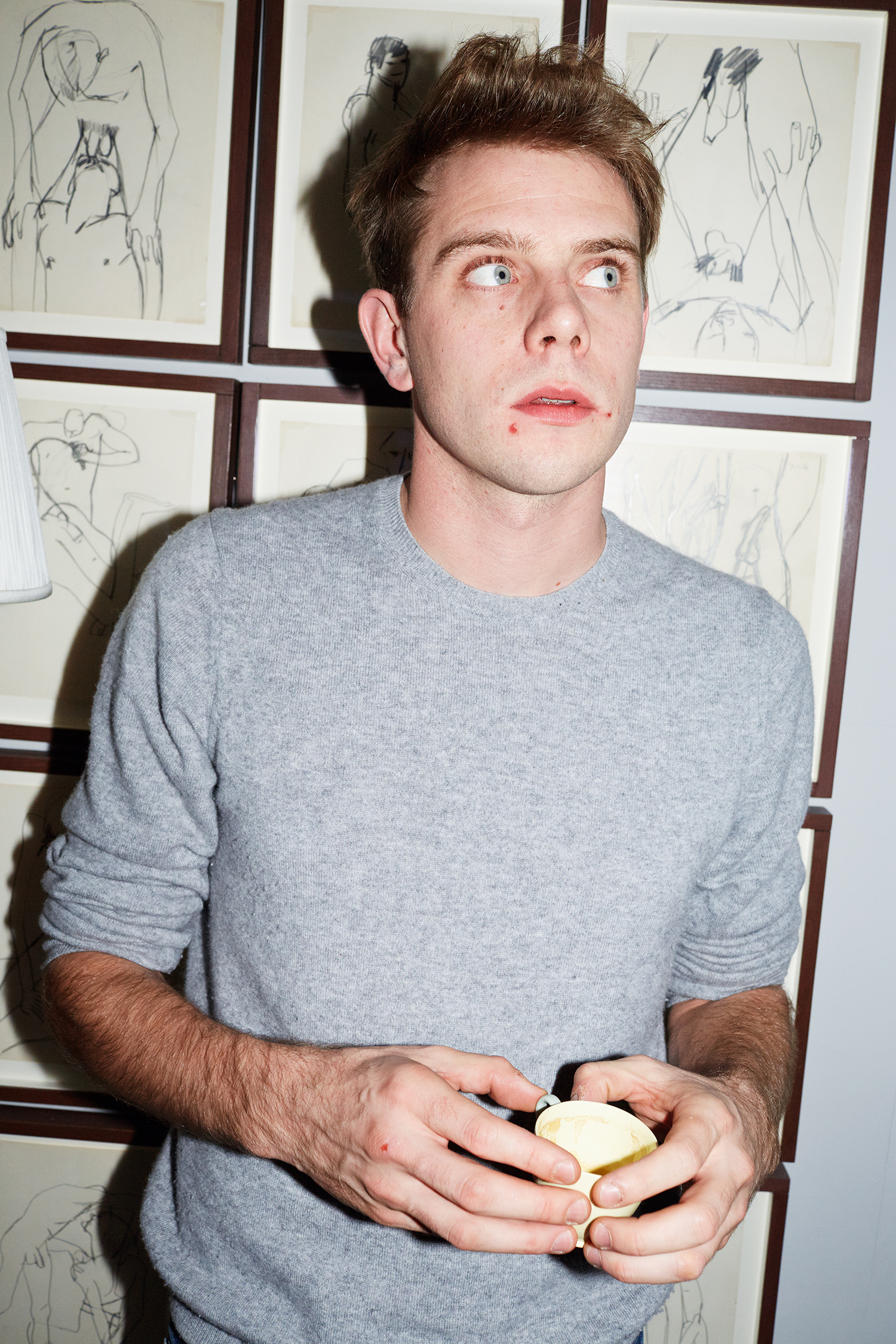

Jonathan Anderson

portrait by JUERGEN TELLER

portrait by JUERGEN TELLER

the neo-minimalist

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

portraits by JUERGEN TELLER

fashion story by OLA RINDAL

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where did you grow up in Northern Ireland?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I lived in a town called The Loup until I was 19. It had a population of 12 families. I grew up on my grandparents’ farm. My parents lived next door.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you like it there?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It’s very green, very gray, and there’s not much sunshine. It’s a very beautiful country because the horizon is very different from, say, Madrid or Paris. You have a lot of open space, but because it rains a lot, I always think of color there as very subdued. There’s no such thing as vivid colors, unless you go into a city like Belfast. Then walls are painted, and these kind of paramilitary paintings go on the sides of buildings. So you have a regular gray landscape and then you have these Catholic or Protestant murals, which are quite interesting, actually.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There are political murals?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, and actually I grew up when it was very tricky. You know, people sometimes forget that Northern Ireland was a very complex country. It was in a state of war. It was obviously part of the UK, but there was a lot of unrest. My parents still live there, and I’m really glad that I grew up there. It’s a country that is very personable. People want to help each other even though certain parts of the population work against each other.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you have a religious upbringing?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Well, not really. My parents brought me up neither Catholic nor Protestant. My parents were down the line, but it would be primarily Protestant there. My parents aren’t very religiously orientated. My father was a rugby coach. He played for Ireland, and he used to coach Scotland, Ireland, and London. He used to play for the Barbarians and for the Lions when he was younger.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Those are big teams.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, he’s 6’6” and looks like a ’70s porn star. My mother was an English teacher.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Literature?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yes. And that’s one of my favorite things about Ireland. This may be me being biased, but I think the Irish had some of the best writers in history. Joyce, Beckett, Bram Stoker, Oscar Wilde — they changed things in literature. They changed what people thought.

OLIVIER ZAHM — These writers were really the literary avant-garde in the beginning of the 20th century.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Beckett would be my favorite. He’s quite popular in France. France loves Beckett.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Very popular.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I love Endgame. It’s really good. And Joyce as well. At the very end of his life, Beckett did so many amazing abstract videos. Like Quad, which

I really liked.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So you were in between a father totally involved in sports and a mother totally involved in literature.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, the thing is that my brother, sister, and me, we were always allowed to do whatever we wanted. My father decided he was to play for the Irish rugby team, and he went out and did it, and I think we’ve been brought up with that idea that if you want something, then go out and do it. You need to do it on your own. We will support you, but we’re not going to support you financially. Go and do it, and if you ever need something, come back.

Cream suede necklace and black leather Twist bag J.W.ANDERSON

Cream suede necklace and black leather Twist bag J.W.ANDERSON

OLIVIER ZAHM — At first, you wanted to be an actor. When did you stop acting?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, it was actually quite serious. When I was very young, I was in the National Youth Music Theatre and the Shakespeare Theatre Company as well. I went back and forth to London and did a lot of plays. Then I applied to the Actors Studio, which is in Washington, D.C., with a branch in New York. I went there to study. I did Stanislavski and Brecht, and then I went on to do the Alexander Technique, which is about realigning your body and blah, blah, blah, becoming a character. I really enjoyed it. I did that for two years, acting in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Richard II. That was great. ButI remember I was always aware of fashion. I enjoyed it. I wanted to dress well, and I enjoyed the idea of brands. When I was younger, I was fascinated by people like Tom Ford.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That was in the late ’90s.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, so you had Tom Ford and magazines like yours. There was Dazed and Confused, The Face, Arena Homme + … It was that moment. Gucci was doing Hawaiian prints and shaving women’s pussies, and it was all very graphic.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Like ’97 or something like that.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It was great. It was one of those moments — and I remember it was just when Hedi Slimane started. He started at YSL, and then he went to Dior. That was ’99, was it? And I think that collection was ’98. He did two amazing collections for YSL that are probably my favorite menswear shows of all time.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Oh, really?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, because I thought they were so modern for a man. I remember being young and being obsessed about getting a pair of trousers. It was like a pair of wide-leg trousers or something. And so anyway…

OLIVIER ZAHM — From Washington, D.C. you were looking carefully at what was going on in Paris?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. I was always interested in fashion. Always bought magazines and always bought a lot of books. Anyway, when I was in year two, I went to New York.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You had a great physique for the stage.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I don’t know if I was very good at it, but I was doing it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You have the voice, too.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — My voice changed. Ultimately, I am so glad that I have that background because I think that fashion fundamentally is about building characters.

OLIVIER ZAHM — With a collection, yes.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I remember the day that I stopped. I’d gone to Baltimore to a house party, and I wasn’t enjoying it. I didn’t feel like I was going to get enough out of it. I didn’t want to do film and…

OLIVIER ZAHM — You wanted to do theater.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I wanted to do theater, but to be a good theater person takes years, and I just wondered if I would ever be good at it. So I dropped out and went back to Ireland. My parents were, like, “You’re paying these bills back.” So my dad was coaching the Leinster Rugby team in southern Ireland. He had an apartment there while he was commuting back and forth. I went to Dublin, and I think for the first three months I was absolutely shitfaced. I didn’t know what to do. I just went out every night. Then I decided to get a job in the menswear department at the Irish department store Brown Thomas, which is part of Selfridges, and I started selling clothes. That was when Tom Ford was at Gucci. It was when Miu Miu was really starting to kick off for menswear. YSL had just got a new creative director. It was a really interesting moment in men’s fashion. Prada was doing a Jamaica collection with feathers on the hats, or no, sorry, lipsticks on the skirts. It was fun. It was a really good moment.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you decide to really get involved in fashion?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I remember one day being in the store, and I was obsessively arranging things on the shelf, mixing products, and someone from Prada came in and was, like, “Oh, you can do visual merchandising?” And he told me I had to come to London to meet this woman Manuela Pavesi. He thought she would like me. And I was, like, “Well, I’m not going to London.” But then it started kicking into my head, so I said to my parents, “I’m going to go to London to just work.” And my parents were, like, “No, you can’t go unless you do a degree.” And so I applied to all the schools, was rejected from every single one, bar a new menswear course that started at the London College of Fashion. I made this imaginary portfolio, and I think they just figured no one’s applied, so, yes, we’ll give you a place.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You went to the London College of Fashion?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It would never have been my first choice, but I’m so glad I went there. I needed a school that I was able to reject. I don’t believe you can learn fashion. You can’t learn to be an artist. You can’t learn to be a singer. You just either do it or you don’t, and you learn from peers. You have to. So I remember going into Prada one day, not shopping, just looking. I was actually going in to pick up a Prada brochure for some university work, and this guy said, “Oh, you never got back to us, and Manuela Pavesi’s here. Why don’t you meet her?” So I met her by accident. And the next week I had a job. I was at university full time and also at Prada full time. So I never turned up to university for basically the first two years. Then I left Prada, finished my degree, and started my brand. I knew I could never work for someone after I worked with Manuela Pavesi.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What did you learn from her? She’s a character, but she’s not a typical fashion person.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — No.

OLIVIER ZAHM — She’s very singular.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — There’s only one. And I think when I worked with her she was mega-tough and uncompromising, had incredible style, seriously intellectual, a full grasp of everything, and I remember being in stores doing mannequins, and she would make me do them over and over and over again, pushing and pushing and pushing. It was a really amazing moment in Prada, when they had pistachio-colored walls. You would have these amazing luxury stores, and then in the middle she would just throw a hundred nylon bags. Or it was like a hundred mannequins, and then they would have bags on their heads, or they would have bags on bags, you know, crocodile bags and nylon bags. I really love this mentality that she had for, like, rich meets poor. Sometimes it was like more, more, more, and other times it was mixing good and bad taste. I’m so glad I learned from her and not from a designer. Because I think, fundamentally, she was a curator and still is. I think she has a very sharp eye and knows how to take the past and reconfigure it into modernity, constructing a fashion, film, and art history.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Preserving something strange.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — There’s always an oddness.

Burgundy merino wool sweater with a candy pink and pale blue nappa patch and forest green nappa judo pants LOEWE

Burgundy merino wool sweater with a candy pink and pale blue nappa patch and forest green nappa judo pants LOEWE

OLIVIER ZAHM — After working with Manuela Pavesi, what was the next step for you?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — After that I immediately started working on my own brand. After I worked with her, it was tough — we’re still friends today — but it was tough. She was really hard, and the reason that was good is it taught me early on that you need a very tough skin to work in this industry. You need to be very focused on what you want, not on what others want. And once you find the vision, that is it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How would you define yourself? As a designer or an art director?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I think in a weird way, I’m not a designer’s designer. I will never be Azzedine Alaïa. That’s not who I am. I will be the first to say, I could never cut a dress. I cannot do a pattern. I could try, I could try anything, but it’s not for me.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you draw?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I draw, I would sketch things. I’m not an illustrator like Karl Lagerfeld would be.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you approach fashion design as something very personal?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — For me, since taking on Loewe and understanding myself better, now I see it as less personal. I was talking to my mum about this a few weeks ago. I used to really care about designing clothes, then protecting them like you own them and thinking they belong to you. About three weeks ago, I was doing the collections and realizing, in working on both brands, that there is nothing more exciting than designing something and getting rid of it when it’s done. I kind of love this rejection process.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you see yourself as an artist?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Fashion is not art, it is fundamentally an exercise of taste. You’re building a wardrobe each season. I’ve done so much research with Loewe, and I went into all the archives. I’d be pulling something out and be, like, wow, another brand’s just done that, but it was done in the ’60s or it was done in the ’70s. I kind of just came to the conclusion that, in fashion, you own nothing, and that’s what makes it amazing.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What you say about fashion also applies to art. You don’t own anything; you have to be reinterpreted and transferred. It’s a permanent investigation and question applied to what’s relevant today.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I think it bogs you down. I spent eight years being bogged down and trying to own something, but when you click out you realize — and with Pavesi, you kind of get that — such an interesting thing: it’s just about releasing ideas. Because fundamentally the minute that a show or image is finished, you have that weird epiphany where you love it and within about 48 hours, you can’t look at it, and you’re done with it. It’s always a very challenging moment. It’s that release.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Would you agree that you’re a child of the ’90s?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So it gives you a foundation.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, I think it’s a generational base. My people are the people who are huge designers today, like Hedi Slimane, Raf [Simons], Phoebe [Philo], Nicolas [Ghesquière], or Miuccia [Prada]. Miuccia’s probably even further.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Martin Margiela?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Martin also. All these people, when I was younger, that was my visual library as a child. That’s what I saw, and I think I’m just a version of that system. That was my color palette, and that was my influence. I’m grateful that that existed.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do people describe you as a conceptual designer because of this?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, because I think fashion was so much more progressive then than it is now.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I agree.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — What is so interesting, and it’s not me being nostalgic and looking back, is that it wasn’t about fashion. It was about creating an image, like a fundamental, sharp image, because it wasn’t over-calculated.

OLIVIER ZAHM — An image that designed or shaped the moment.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. Now we overcook things. I think that’s to do with Photoshop and perfectionism. We want things glossy. We went through a glossy period. When we went to do the Loewe campaign, for example, with Steven [Meisel], it was so exciting. When I first applied for the job, they asked me what I thought this brand should be, like what is Loewe? I remember coming in; I’d made a small booklet, and in it were the images that were in the campaign. And for me, they were already there. The beach: that is Loewe. I don’t care if the garments are mine or not mine. It didn’t bother me. That woman still exists today. That image, there is no point in me asking Steven to recreate it. I would rather have him shoot a silhouette.

Orange wool suiting jacket, black cotton pants, and black leather shoes J.W.ANDERSON

Orange wool suiting jacket, black cotton pants, and black leather shoes J.W.ANDERSON

OLIVIER ZAHM — I don’t think any brand has used an existing fashion image from an old editorial for its advertising.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Helmut Lang used art pictures — like those of Robert Mapplethorpe — this way. I love this idea of taking something from art and then making it a fashion image.

OLIVIER ZAHM — People put too much stock in the present. What’s going on now is really informed by the past. In your Loewe campaign with Steven Meisel, the way you align the moment with the ’90s makes a big difference because people tend to forget. There’s no memory anymore.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — There’s no memory, but in some weird way it’s like even the ’90s have no memory of the ’60s. With each generational shift of stylists or image-makers, they go for a period. And then it ends, and now we’re living in a decade where more and more information is uploaded onto the Internet everyday. Billions of pictures go up everyday. So you can type in anything and find whatever you want. Now, as time goes on, you see people taking pictures of images, images of pictures. Everything is rescanned until it’s a photocopy of itself. So when I went to tackle Loewe, it had to be fundamentally what is happening, which is young consumers of my generation, who are now starting to earn money, grew up with that period where Tom Ford, Hedi Slimane, and Miuccia Prada, all these different people were expressing themselves without the formula that exists today. That will always be an influence on me, and I will never be shy to admit it. Because fundamentally I think it’s important. It’s the passing of information. There’s information passed from them, from the previous thing. I feel like you have to ultimately let go and not really become precious. I think we became over-precious in the last 10 years. And what’s happened now is the Internet has just said — poof.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But this generation of, let’s say Hedi Slimane and even Miuccia, they were fighting against the previous generation, proposing something radically different as a statement against what happened. Today, I have the feeling that your generation of designers, they don’t fight anymore because they don’t see an enemy. They don’t see what to fight because everything is there and it’s always an option. But there is not an instinctive reaction against something.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — This can be a pro and a con in the dynamic of my generation of designers, I must admit. Because, in a weird way, you nearly end up fighting with yourself.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You don’t know which aesthetic to fight against.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — You don’t know whom to fight, and there are so many designers that things are so fast now. I think it’s good that people aren’t being over-calculating. I work very closely with the stylist Benjamin Bruno, and when we are working it’s very spontaneous.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How do you make things relevant for today, then? What’s your approach? In every article you’re described as a provocative designer. But I don’t see that.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I don’t see that, either. I think that’s a lazy approach to it. When we did men’s collections before, people thought they were hyper-provocative, but I think that’s because we’re not used to clothing anymore.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Yeah, because men’s clothing is more conservative.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. But it used to not be. The ’80s were incredible for menswear. When I worked for Versace, it was incredible to see the archives of what they did.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Without it being extravagant or overdressed.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I always think the menswear that I do at my own brand disturbs rather than provokes people.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You always use menswear material as a start.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — As a start, but then we’re using them in cuts where they are morphed or changed in a way. I’ll never forget the time that we did a collection with ruffled shorts and knee-high boots. When we were doing the collection, it was totally normal. When you’re in a studio, everything is normal, and it’s that reality moment when you put it out, there’s a bluntness. I’m extremely blunt. I like either yes or no. It’s either black or white, that’s it. When I do something, I do it and that’s it. There’s no trying to please someone. I’ve run my own brand for eight years, and we never went bankrupt, do you know what I mean? We’ve had moments where we could’ve, but I’ve never gone at it to provoke people because I think that’s a trick.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you decide to start doing womenswear?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — The first women’s collection we did, the collection wasn’t done just to do womenswear, but to get the volume in fabric higher to be able to get the menswear produced. That’s how it came about. So when we started men’s, the volumes were like 20 shirts and 20 t-shirts, so we sold more fabric; we had to do women’s. So we then just did the collection for women. We actually just used the men’s on women in the first show. And it was a moment where London was not doing daywear: it was about a cocktail dress. It was about a printed dress, a shift dress.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You started at the moment when it was all about dressing socialites.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. Everyone else was working with this kind of formula, and we were doing a collection where it was Dr. Martens kind of boots with fur coming out and paisley pajamas with rubber necklines and fur on the back. But it was all menswear. We took the seams out and made it all smaller for women because we didn’t have the money. It was out of a need to take one sample set and get two collections out of it. And be able to sell more volume. So I fell into women’s that way. It was out of a need for the men’s to work.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Let’s talk about the transgender or unisex aspect of your work. What is interesting is that you don’t seem to really care about the difference of gender when you design. Is that right?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. I think it boils down to the nonsexual part, which is clothing. Looking at clothing as objects. For me it’s like sneakers, jeans, t-shirts, white shirt, black jeans, normal jeans. A duffel coat is another example. Each year, as time passes, these things, every so often they shift and go into this unisex world. And I’ve always been fascinated…

Yellow wool suiting blazer and black wool pants J.W.ANDERSON

Yellow wool suiting blazer and black wool pants J.W.ANDERSON

OLIVIER ZAHM — By the common domain.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. It’s where an object looks good on both a man and woman, but means fundamentally different things on them.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Like furniture.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah, but it’s kind of like Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe. Patti Smith wears a t-shirt, which is oversized, and then he wears a t-shirt of hers, which becomes tight. They’re the same object, but they mean two different things.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Both sexy.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yes. And I was obsessed by this. You know, the white t-shirt will always exist. It’s there. The pair of jeans is always there, and I love that quote where Saint Laurent wished he created the jean. I think everyone wished they created the jean and the white t-shirt, you know, because these things fundamentally look sexy on everyone, and the bottom line is that I create fashion because I think it’s the rejection of the idea that I wish I would be able to just design those two objects. It’s that striving to find that one thing that can be in both. That’s always pushed me in terms of both men’s and women’s clothing. I could never function without the other because I don’t think society works that way.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The intersection between men and women is an interesting place to work because you don’t have so many designers who do that. Hedi Slimane was an example. Rick Owens, maybe.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Rick Owens, Hedi Slimane, Miuccia. There’s probably a lot of others. Even Polo Ralph Lauren, which is a completely different thing, but I think it’s another example of it. The period I grew up in was influenced by someone like Hedi Slimane, who defined fashion as not about the street, but as something androgynous. Possibly, it was about garments, but you didn’t know where they stood.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What do you think you bring to men’s fashion?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — One of the most exciting things I believe we did in men’s was actually the simplest thing, which was when we put a man in only a coat and shoes. It took the coat into a sexual performance but not. It was that kind of dichotomy. When I look back, I think those looks were always the strongest because it is a singular thing that is actually fundamentally tangible, a reality, but it’s a way in which you propose the character; it’s just about a garment. It’s not about styling. It’s just about the piece and the way in which you access it.

Blue cropped éponge top and mini-skirt, silver plated brass Puzzle choker, and blue leather heels J.W.ANDERSON

Blue cropped éponge top and mini-skirt, silver plated brass Puzzle choker, and blue leather heels J.W.ANDERSON

OLIVIER ZAHM — Let’s speak about your team, the people around you.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I couldn’t do it without the stylist Benjamin Bruno because we confront each other. We’re really close friends. We push each other and believe in the end goal. He’s one of the sharpest people I know, and we work very well together.

OLIVIER ZAHM — He’s been working with you for a long time, almost since the very beginning.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Nearly from the very beginning, yeah. You know, I met him with Carine [Roitfeld] at a showroom, where I had done t-shirts in collaboration with a photographer’s archive. The next season I started working with him.

OLIVIER ZAHM — He was working with Carine?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. He was her assistant at Vogue.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What does he bring you?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It’s a dialogue. There’s nothing better than someone who says no. He is the only person I can have a confrontation with, and the next morning it’s fine. Wake up and go back to work again. You need that. You need traction to make things work. We don’t worship each other. In fashion, there’s nothing worse than worship. It’s a very dangerous thing, and he’s incredibly talented. I admire him, and I think when you find someone to work with, that’s it. It’s a very balanced formula. For successful brands to work, you have to have that person, and it is about collaborating. I’ve always been completely transparent about my team. Without them, I can’t do this job, it’s impossible. You know, I work with another team at Loewe, and they challenge me in a completely different way.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Are you against the idea of the “star” designer?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It’s about teamwork. Because the days of people believing that one man does the whole thing are over. I am just a front man who has to lead everyone in one direction. You need conviction to be able to make things work. Especially when you’re driving two brands; you need to have the confidence for people to believe it’s working. Ultimately I think that’s the key to things.

OLIVIER ZAHM — These days, it seems we’re lacking true emotion in fashion. It’s more and more rare to find emotion behind strategy, tactics, and the perfection of professionalism.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — People became too guarded. What I loved about the Loewe campaign, what I took from it for my own brand, was even though this is a luxury brand, the minute you overthink this, it doesn’t feel real. I think the past 15 years have been over-thought and controlled. You know designers were very controlled. And the images were Photoshopped and reduced and slimmed to the point at which we are so used to looking at perfection, it’s actually too perfect.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How do you deal with the problem of doing advertising campaigns made to sell bags?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — My biggest objection with bag brands was that they shouldn’t be presenting an image that sells a brand. You don’t need to tell a customer that the woman has to hold the bag. They should know to hold the bag. It sounds ridiculous, but there’s nothing more awkward.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So you treat the bags as objects.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It’s a functional object. And the human condition tells you that you hold the bag. You need to sell the character before you sell the bag. You can’t do it the other way. Because you need to let the person decide how to wear it. And the minute you tell people what to do, it’s boring.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I agree. So that’s something that belongs to you. You have a love for design and for objects. Not simply fashion design, but also furniture design, interior design, window design.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. I worked in visual merchandising. We had three stores when I joined Loewe that were about to go into the old concept, and I worked with the in-house architect to do it from scratch. Omotesandō was one. We’re doing Miami, and we just did Milan. I wanted them to be like going to someone’s house. I wanted bags to live in a landscape like that because fundamentally someone buys a bag and they go home and dump it on the ground. So what is that environment for Loewe? For me, instead of getting someone to recreate everything, it was better to go and find the best example of something that is personal to me.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Not necessarily something Spanish.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — No, the Spanish part is where it’s made. I think that will always ooze from it. You will always get that from it. But I felt like I am part of this brand. I take full responsibility for it. So when you go into the store, I want people to feel that they could understand me, and that they could be at home. And obviously, that’s going to take time to register, but I wanted people to think here is an incredible and original Rennie Mackintosh chair. I think that object and that bag have the same energy. That chair would be my dream if I was to come home and throw my bag onto something. That chair is not perfect anymore; it’s being lived in. You can see that it’s being sat on; it’s being worn. But it’s just good modern design.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But then it’s not a formula. You need to design and curate every shop.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I would love that. I feel like so far, the idea would be to do that. I hope. Every shop is different. In Omotesandō, we collaborated with Hamada, whose family was one of the most influential ceramicists of the last couple of centuries. Their family created, and so we put all three generations on a shelf.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Which other furniture designers did you put in your shop?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I’m obsessed with Christopher Dresser, who was an amazing designer and design theorist. He was before Bauhaus, but the Bauhaus looked to that. And in Omotesandō we placed a William Morris chair, which is a hyper-classic. Try to beat it today — you can’t! When I had to work on the Milan shop, we worked with someone else and had other elements. We had a library chair; it’s covered in our leather, but the actual structure is what was designed for Liberty ages ago. But it’s just a good chair. I believe in the character sitting with the bag on the ground and reading a book in that chair. I like this idea that instead of these objects that you would see at a museum, you can see them and find them in a real-life situation. The idea of luxury is a very dated thing. To me, stores are cultural because they are places that can affect people’s eyes. On the street, these things affect you. I want to try to challenge luxury and what it means for people. I want people to go in the Loewe stores and feel like they are at home.

OLIVIER ZAHM — From your point of view, how has the luxury world changed?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I feel like people have changed very quickly in the last 10 years what they feel about luxury. The Internet makes designers closer to consumers. You can talk to consumers quickly.

Cream double-faced hemp mini dress J.W.ANDERSON

Cream double-faced hemp mini dress J.W.ANDERSON

OLIVIER ZAHM — Which you do with your Instagram. It’s incredible. You give a lot of great information about the way you work and what inspires you.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I must admit, I like Instagram because I think it gives me the rhythm at which I see things. So if I’m in a showroom, and I’m excited about something. I will show that excitement as much as if I’m in my garden and I feel like I’m relaxed. I want to share that because consumers have to buy. They have to part with their money, so in this modern world, you have to give a lot. You have to keep a lot private; you’ve got to protect yourself, but you also have to give.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You share your enthusiasm and excitement.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Because I’m genuinely excited. I’m excited about life. I think if you were to ask me three years ago, I didn’t know where I was going, but now I feel like I’m very lucky to be in this position, and I want to share it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’re in these two worlds, your brand and Loewe. How do you divide that?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Well, I have two Instagrams. I’ve got one for myself and one for the brand. But I do them both because I feel like there’s two different aspects. One is J.W.Anderson, and one is a hybrid of both. It’s interesting, and it’s weird. I went back through the pictures recently. It’s so fascinating what you see in a year. Life has to be exciting; you only do it once, so I’m not here to compete with people. I’m here to say, “Look, this is what I’m doing and you know, engage or don’t engage.” Social media has its pros and cons. I think that one of its pros and one of its cons is that you have to protect part of yourself, the part which is you. When it comes to the weekend or when I’m not working, that’s my time. I do whatever I want and separate.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How many collections are you doing now?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It’s six collections for J.W.Anderson, four for Loewe. So it’s a lot. I’ve got resort for J.W.Anderson, but not for Loewe. And that’s why you have to be very strict with yourself. My day starts at six in the morning, and I work until six in the evening.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How do you organize your day?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I’m up at six. Go to the gym or do something personal. Start the day, clear out, get aggression out, and off you go. And I have meetings bang, bang, bang, an hour. I’m very quick. I have a great team, so I can be very direct. People sometimes find me a little difficult. But I’m very straightforward; there’s no bullshit. I say what I like and what I don’t like and move on. There are too many categories. So there are going to be moments when I’m not perfect. There are going to be moments when shows are amazing and when they’re not as good, but if you don’t do that, if it was perfect all the time, it would be mega-fake.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You work so much! Are you a workaholic?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I am. But I never wake up in the morning and feel like I’m working. For me, the biggest killer for my type of character — which I’ve really started to realize in the last two years — is boredom. I would rather work than be bored.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What about taking a vacation?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — In a vacation, it takes me about the first week to even shut down, then the next week I’m in full swing, never wanting to go back, you know, on a beach, going to nightclubs. But then the last two days is like the psychology of going back, and then it takes me a week to get back. Once I’m in it, I’m fine. So it’s a monthlong process.

Latex dog print t-shirt and pop yellow nappa judo pants LOEWE

Latex dog print t-shirt and pop yellow nappa judo pants LOEWE

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’ve been able to rebrand Loewe in a very exciting way, and that’s pretty rare. Phoebe Philo did it with Céline, but there are not so many examples of people who are able to redesign and reinterpret a long story without giving you the feeling that they’re trying too hard, and it’s too obviously a reference to the past.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — When you look at someone like Phoebe, that’s so respectable because she believed it was going to work. She just believed it. That’s what it looks like to me. I don’t know her, but when I look from the outside, it just looks like a woman with conviction, and that’s what you need. I love what Nicolas [Ghesquière] does, I love what Phoebe does. I love what Miuccia does and Rei [Kawakubo] because there is conviction. I think the key to these sorts of things with heritage brands is to ask what are the good points and what are the really bad points. Then you just draw the line in the sand and say, “I’m going to focus on that part.” There’s 100-something years of it, but those brands when they started never went out to be old-fashioned; they went out to be modern. In hindsight, when we look back, we look at them with nostalgia. But you have to ask what is modern right now. Loewe used to make loads of trunks, but people traveled on ships. Now we’re on easyJet flights with luggage restraints. So there’s no point; that doesn’t exist anymore.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Can you name a designer from your generation that you like?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — There’s one new designer. A kid called Craig Green, who does menswear. He’s done collections I relate to. I think he’s sharp. I don’t know what age he is, but I feel that for a “young” designer, he’s the sharpest at the moment.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Would you consider Gareth Pugh as your generation?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Yeah. I love what Gareth does. He’s a bit older than me. He’s mega-sharp, and I like that he is also uncompromising. When I was at Prada, I always thought Miuccia’s menswear was so radical. It was such a radical approach to things. You know, Rick [Owens] is incredibly radical because it feels like it spiritually comes out of him.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s surprising to realize that you’re succesful, but not competitive.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I love being excited by other designers, and that makes this industry exciting. I think the minute you start competing, it becomes a problem. Because you lose focus. Whereas when you see the good in something, and you embrace it, it’s exciting. It’s like, “Wow, I’m part of a system that has Rick and Rei and Miuccia and Nicolas.” They all coexist, and they all sell products.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And that’s the philosophy of Dover Street Market.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — Exactly. For me, Rei Kawakubo was able to create a platform that was an edit of how fundamentally fashion can exist on all levels, from Supreme to Prada. A wardrobe is not one rack of a full look. It doesn’t work that way. Women don’t dress that way. They want to be able to go, “I want this and that and that.” And they make it their own. And it feels real.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you feel like your success happened too quickly? Were you prepared for the pressure?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I’m prepared for the pressure. I think the day before the Loewe show, I felt like I wasn’t prepared, but sometimes it’s just about jumping into cold water. You don’t want to do it, but when you get in, you’re actually warm. And I think I’m prepared because I actually have been doing it now with my own brand for eight years.

portrait by JUERGEN TELLER

portrait by JUERGEN TELLER

OLIVIER ZAHM — What’s your dream for your namesake brand?

JONATHAN ANDERSON — I wanted to create a brand that one day, while I’m still living, someone will do in my name. Because there will be someone younger and better to do it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That’s beautiful.

JONATHAN ANDERSON — It’s like Loewe. I’m hoping there will be a period where someone will take over and be better at it, but as long as I have protected it someone else can go in. I always think that when you do something, a job, you have to take responsibility for the people involved because ultimately you’re employing them, you’re putting money into countries, you’re exciting people. If you respect it, and you don’t bastardize it, then the next person has an enjoyable experience from you. I want to repair Loewe back to its best moment. With my own brand, I want to create something that someone else can use as a platform, too.

END