Purple Magazine

— The Los Angeles Issue #30 F/W 2018

laura and kate mulleavy

los angeles

fashion

rodarte

laura and kate mulleavy

interview and photography by OLIVIER ZAHM

family pictures courtesy of RODARTE

Two California sisters, Laura and Kate Mulleavy, put Los Angeles on the fashion map in 2005 when they created the Rodarte label. They won instant international recognition for their dark, feminist, deconstructed clothing, influenced by science-fiction, anime, and horror films, as well as by a DIY anti-conformism. What wasn’t evident in their style, they made visible in Woodshock, their 2017 film starring Kirsten Dunst, which was partly shot in a redwood forest. The film reveals the deep psychological influence of California’s natural landscape on their style.

ACTRESS KIRSTEN DUNST ON THE SET OF WOODSHOCK, 2015, PHOTO AUTUMN DE WILDE

ACTRESS KIRSTEN DUNST ON THE SET OF WOODSHOCK, 2015, PHOTO AUTUMN DE WILDE

OLIVIER ZAHM — Are you guys from Los Angeles?

LAURA MULLEAVY — Our parents are from Los Angeles; both grew up in LA. My dad’s family is fifth generation from Sierra Madre, which is a small mountain town in Los Angeles. But my sister and I grew up in Northern California, in Santa Cruz. Our parents were both going to Humboldt State University — which is the area where we shot our movie — and then my dad got his doctorate from Berkeley. When we got older, we came to LA.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your movie, Woodshock, has incredible forests, mountains, lakes — is that where you grew up?

KATE MULLEAVY — We grew up in redwood country… near Big Sur. Where we shot them, farther up, in Humboldt [County, California], they’re some of the largest living organisms on the planet. They’re huge. The ones in Big Sur, which people are more familiar with, are tiny compared to those in Humboldt. It’s an out-of-body experience to see these trees. I always tell people what a soulful experience it is to see them. It’s like what astronauts say about going into space and realizing how small they are in the grander scheme. People have introspective moments in the presence of these trees because they’re thousands of years old, and they only exist on a small strip of land in California, and nowhere else in the world.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What did your parents do?

KATE MULLEAVY — Our dad’s a botanist. He’s a mushroom expert… He worked on every kind of mushroom. He studied small ones, slime molds, fungi. The ones that are dangerous. You know, between hallucinogenic, edible, and poisonous…

LAURA MULLEAVY — Our friends always ask my dad to identify mushrooms for them. I always thought of my dad as a scientist. Only later in life did I realize the artistic process of science. Nowadays, people are more tuned in to the things my dad was studying, which are linked to greater questions about the universe, nature, biology.

KATE MULLEAVY — Spores are such a weird, prehistoric concept, yet they have a connection to the life process.

LAURA MULLEAVY — The people we grew up around were mushroom experts. You could just go out in the woods and pick them.

KATE MULLEAVY — They grow really well there. We have pictures of my parents leading mushroom hunts in Berkeley, when my dad was getting his doctorate. He always said we had a funny parallel in fashion: our first collection was inspired by mushrooms.

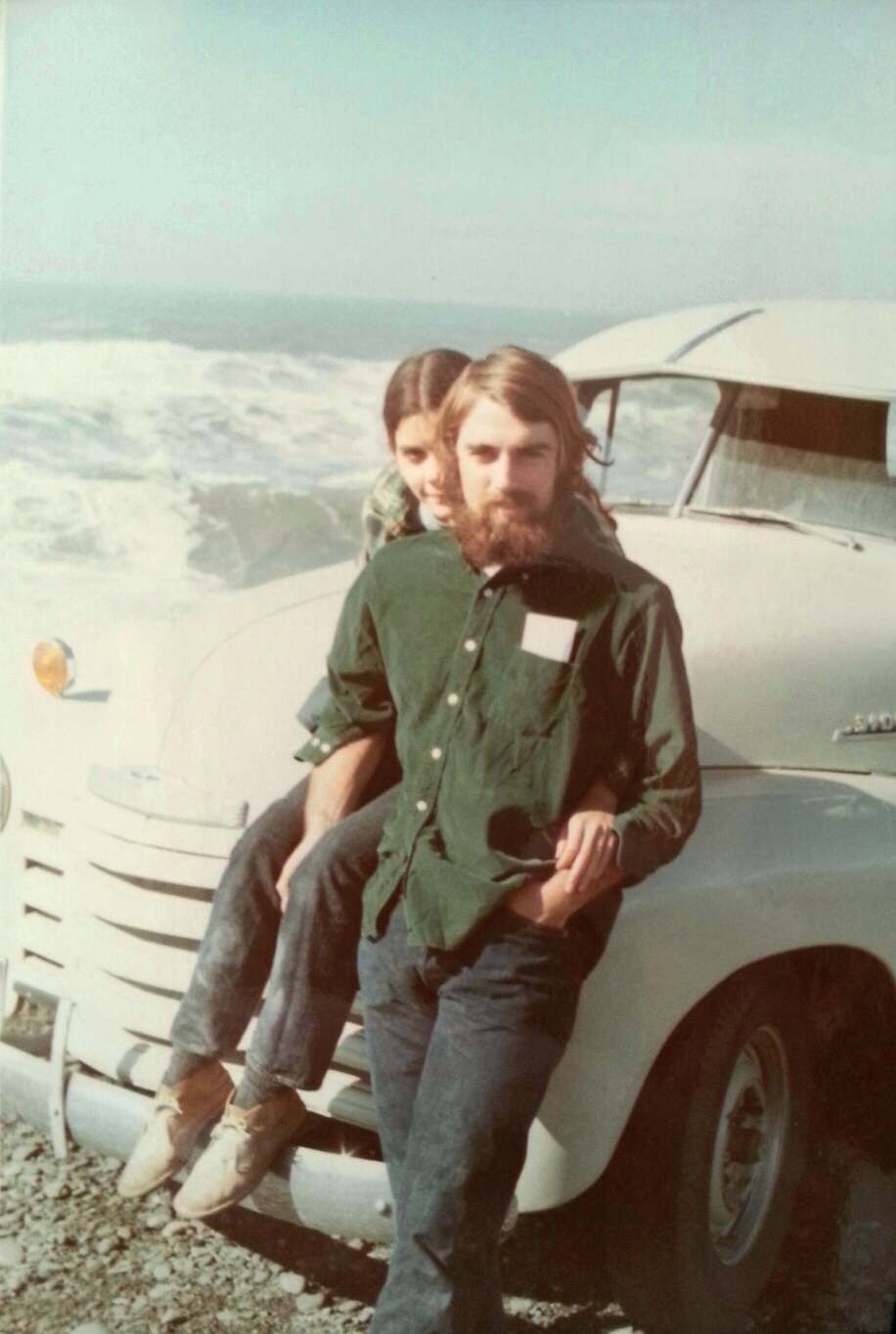

VICTORIA AND WILLIAM MULLEAVY (KATE AND LAURA’S PARENTS), 1971 PHOTO WILLIAM MULLEAVY

VICTORIA AND WILLIAM MULLEAVY (KATE AND LAURA’S PARENTS), 1971 PHOTO WILLIAM MULLEAVY

OLIVIER ZAHM — I had no idea that your fashion was related to mushrooms!

LAURA MULLEAVY — Yeah.

KATE MULLEAVY — From the very beginning. When we first did our collection, we went to the Vogue offices, and André Leon Talley was in the room with Anna Wintour. We were just out of school and didn’t know anything. I remember saying something like, “This dress is inspired by a fungal shelf.” André Leon Talley couldn’t believe it.

LAURA MULLEAVY — He said, “In all my years, I’ve never heard that before.” [Laughs]

KATE MULLEAVY — Later, we said, “This dress is inspired by redwood bark.” That was the early stage. As you do things more and more, your voice evolves, and you find the things that inspire you. Nature was a huge inspiration for us.

VICTORIA AND WILLIAM MULLEAVY (KATE AND LAURA’S PARENTS), 1971 PHOTO WILLIAM MULLEAVY

VICTORIA AND WILLIAM MULLEAVY (KATE AND LAURA’S PARENTS), 1971 PHOTO WILLIAM MULLEAVY

OLIVIER ZAHM — And nature is back, in your movie.

KATE MULLEAVY — The fragility and violence of nature, and the connection to human psychology. For us, the film was about an interior experience of life and death, from a woman’s perspective.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Fragility, anxiety … a spectrum of emotions — which is sometimes more difficult for men to understand.

LAURA MULLEAVY — Yeah. It’s different. Women are different.

KATE MULLEAVY — We saw the rerelease of 2001: A Space Odyssey last night, at the Cinerama Dome, in Hollywood, and what you’re seeing in the film is the closest thing to what my dad experienced in the ’60s when he saw 2001. There’s no digital remastering. They restored the actual film and projected it in 70mm. You see all the flaws. Watching it, I felt it was a great example of how you can let go of narrative logic and communicate something greater about the human experience and emotions — even though the film is about the logic of HAL, a computer. I realized how masculine HAL’s perspective was.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Gender difference: men going into space, remote exploration, versus women on earth, and inside their emotions…

LAURA MULLEAVY — Well, these roles are all socially and psychologically created, and in them, the idea of reproduction and exploration have been separated: men explore externally, and women have internal exploration. But women have never really been able to vocalize it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Is that what you’ve tried to express?

KATE MULLEAVY — One of the challenges for us, when we were working on our film, was how to show a woman having an existential crisis. In our film, Kirsten Dunst’s character takes a mind-altering substance, which leads to her death, although some people might see it as the opposite of death and more like a transcendent state of ecstasy. Her crisis is one of the tropes you notice whenever a woman is represented in film or literature, particularly a woman who takes drugs, which often leads to the worst possible scenario.

LAURA MULLEAVY — So, in our film, a woman takes something and puts into question not only the peril and the fragility of life, but also of nature, and the idea that human beings are essentially destructive. Whether it’s toward ourselves or the earth. People might not know this, but where we shot the film, over 90% of those redwoods had been torn down.

KATE MULLEAVY — Logging was the biggest industry in California — bigger than the Gold Rush. In the 1800s, most of the California economy was based on cutting down redwoods. That was happening through the 1990s, and still happens. Now there are interventions to try to save the tiny percentage left. We had this idea of creating a psychological experience where someone internalizes that violence, and then she goes through a transformation in different versions of death. Slowly she disconnects from the world around her, so there’s no inner connection, no connection with the characters around her, and more and more she retreats inward.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Were you trying to explore a feminine character that didn’t have to connect to men?

LAURA MULLEAVY — Yes. And it was very difficult because if we brought a man into view, people immediately wanted to know about that guy and what’s the connexion with her. But that’s not the point of the movie. Men are there, but they’re a mystery because she doesn’t understand them. That was a hurdle to get over because people are used to seeing characters whose social roles mean something. In this film, they didn’t mean what was expected.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It also seems to be a story about isolation. Here in California, there is always an attraction for escapism, disappearance.

KATE MULLEAVY — Well, you should see where we shot it. There’s a lot of that there.

LAURA MULLEAVY — If I set up phone calls with people from around the world, Pacific Standard Time is the most difficult time to set up for anybody.

KATE MULLEAVY — This attraction is the power of nature. All the way into the Mojave Desert, which, along with giant redwoods, offers some of the most dynamic landscapes in the world, and all in one state.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, could your fashion be described as artisanal?

KATE MULLEAVY — Well, we’re emotional about the clothes we make, but there’s always an idea behind it. Sometimes, a collection looks beautiful to the eye, but the viewpoint behind it is always, for us, conceptual. The clothes aren’t necessarily heavy-handed in their aesthetic or conceptual approach. What makes our clothes unique is that there’s usually something slightly off-focus.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How so?

KATE MULLEAVY — When it’s pretty, it isn’t simply a pretty, elegant dress. It can be that, but then it can go somewhere weird. And it might not work on a red carpet. Sometimes, it may seem like red-carpet apparel, but then people might think it doesn’t quite have that very ladylike thing red-carpet clothes are supposed to have, especially if the inspiration for a specific collection was something a bit different.

LAURA MULLEAVY — That’s our style.

KATE MULLEAVY — The collections that are the most “us” have things that are slightly off about them. I think that has a lot to do with growing up here.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s something scary about nature here, putting almost everyone in a state of psychic isolation.

LAURA MULLEAVY — It’s also kind of addictive. The hard part is to leave it. Now that fashion has become so global, there’s less of the straightforward interaction, and you find it easier to stay away because people everywhere have things at their fingertips.

KATE MULLEAVY — A few years ago, we did a collection that spoke about what you just said about the scariness of nature. People might not realize that LA is right near Angeles National Forest. In about a 40-minute drive, you enter an entirely different world. The collection we did was inspired by Death Valley and this really crazy transformation myth that we made up, in which a woman goes into the desert and is reborn as a condor. It all happened in the desert.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did that influence the collection?

KATE MULLEAVY — All the pieces and materials were hand-burned and sandpapered — all heavily reworked. We were burning fabric, and I kept thinking, “This is my worst nightmare.” But I knew it was going to be interesting.

LAURA MULLEAVY — All of the fabrics were aged.

KATE MULLEAVY — Then, all of a sudden, there was a giant wildfire in the forest.

LAURA MULLEAVY — The following morning, everywhere around, cars were covered in ash. But the fire wasn’t near us. The wind brought the ashes in. And Alexandre de Betak, who produces our shows, was in town and kept saying, “What’s the inspiration for the show?” We said: “Welcome to the wildfires in LA. That’s what this collection is about: fire.” It was crazy that he could experience that.

KATE MULLEAVY — He set off green smoke during the show.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s a dreamy aspect to your fashion, but also something dystopian…

LAURA MULLEAVY — Yeah, the two things go together, always.

KATE MULLEAVY — Our film wasn’t one you’d watch and say, “Oh, there are all these fashion clothes in the movie.” Yet the film does relate to us as designers. The beauty and thoughtfulness of the aesthetic, if you really look at it, is also about something inherently disturbing, about what I was saying earlier: the capacity for human violence, and what that means.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What do you like in fashion design?

KATE MULLEAVY — It’s an exciting medium to work in, especially if there’s something you’re trying to say. One aspect of clothes which is interesting for us, is their function as a form of social commentary, as a means to liberate yourself and change how people look at you.

KATE MULLEAVY — Well, when we made the movie, we didn’t realize how much we had to say about being a woman.

LAURA MULLEAVY — We couldn’t even fit everything into one film, either. I thought, “Okay, we have to do a second one.”

KATE MULLEAVY — I remember being on set with Laura, and we were shooting the scenes of Kirsten Dunst looking in the kitchen cabinets and then in the bathroom. We’d spent three or four days on set. We were meticulous because Kirsten, Laura, and I all knew we were saying a lot about the domestic space, and about being trapped in it as a woman, and what it’s like to be a woman, and how people hear your voice,

or lack of voice. I remember saying to Laura, “I didn’t realize this movie had such a feminist perspective.”

OLIVIER ZAHM — What’s the difference for you between working on a fashion collection or a film?

KATE MULLEAVY — There’s a huge difference! A film is very emotional. When you finish a movie, you feel like you’ve given away a secret about yourself. And maybe it’s one you didn’t really want to share, but you did. Then it feels like an emotional experience. At one screening in LA — and everyone has different experiences when you screen a film — one woman, who came out crying, said to us: “My mother died recently, and I’ve had no words to explain what grief felt like. And watching this movie, for me, I felt like I had no sense of time … and the film captured how I feel.” That’s when

I realized the power of filmmaking. Although in fashion shows, you touch people in different ways. We have creative conversations with people who are very close to us. We share something more primal in fashion, maybe.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But as designers from Los Angeles, you’ve brought together the cinema and fashion worlds, not to mention their main common point: the red carpet. And the costumes… Because you’ve done costumes for films. Yet it seems there’s not so much connection between them anymore.

KATE MULLEAVY — People forget how important costume design is to films, and how it changes the way you think about a character. That’s so crazy.

LAURA MULLEAVY — In the film community, costume might be the least important of the creative guilds. I think it’s because it’s considered women’s work. I grew up loving film because you’re transported by the way something or someone looked.

OLIVIER ZAHM — For example?

LAURA MULLEAVY — I loved Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo and The Birds when I was young, not just for the films, but also the costumes.

KATE MULLEAVY — They also tell the story. In The Birds, Tippi Hedren’s perfect little green suit is ripped apart by birds.

LAURA MULLEAVY — I’ll never forget the Alexander McQueen show that referenced Hitchcock’s blondes. And Tom Ford referencing Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant. After all, designers and film directors are just telling stories. And women’s stories, too.

END

RODARTE STUDIO E 12TH ST LOS ANGELES CA 90023