Purple Magazine

— S/S 2010 issue 13

Terry Richardson’s Life Story

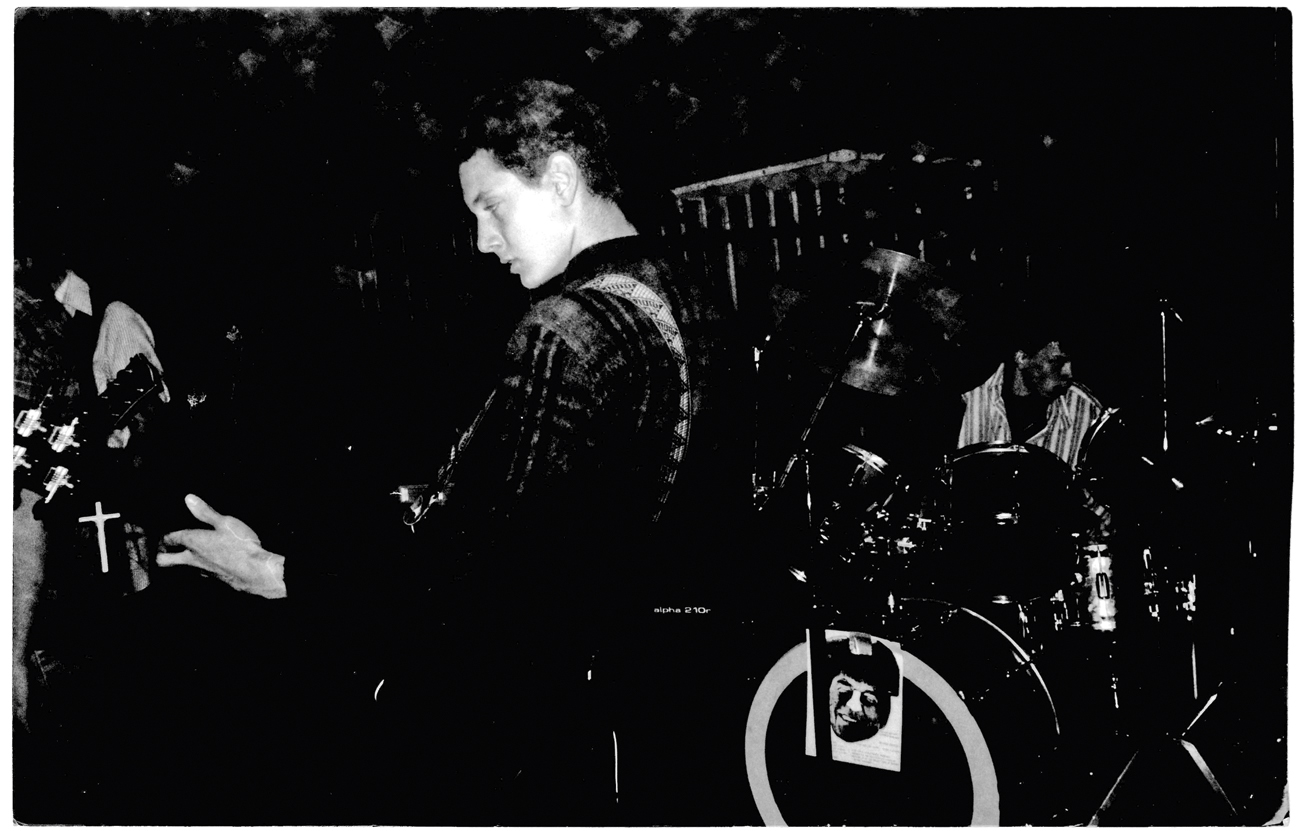

Terry Richardson playing bass in his band SSA in Erik’s backyard in Ojai, California, 1982

Terry Richardson playing bass in his band SSA in Erik’s backyard in Ojai, California, 1982

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

episode 4

Age FOURTEEN to EIGHTEEN

OLIVIER ZAHM — Here we go — the fourth episode of our interview: The teenage years, 14 through 18!

TERRY RICHARDSON — All right! The teenage years — lucky for some, unlucky for others.

OLIVIER ZAHM – Were you still living in LA?

TERRY RICHARDSON – Yes, in the same apartment building, The Villa Valentino, on Highland, three or four blocks up from Hollywood Boulevard in Hollywood.

OLIVIER ZAHM – And your mother was still recovering from her car accident, right?

TERRY RICHARDSON – Yes. I mean, I was nine when she had the accident. She had only partially recovered. She could walk with a cane, but because of the brain damage she was never going…