Purple Magazine

— S/S 2010 issue 13

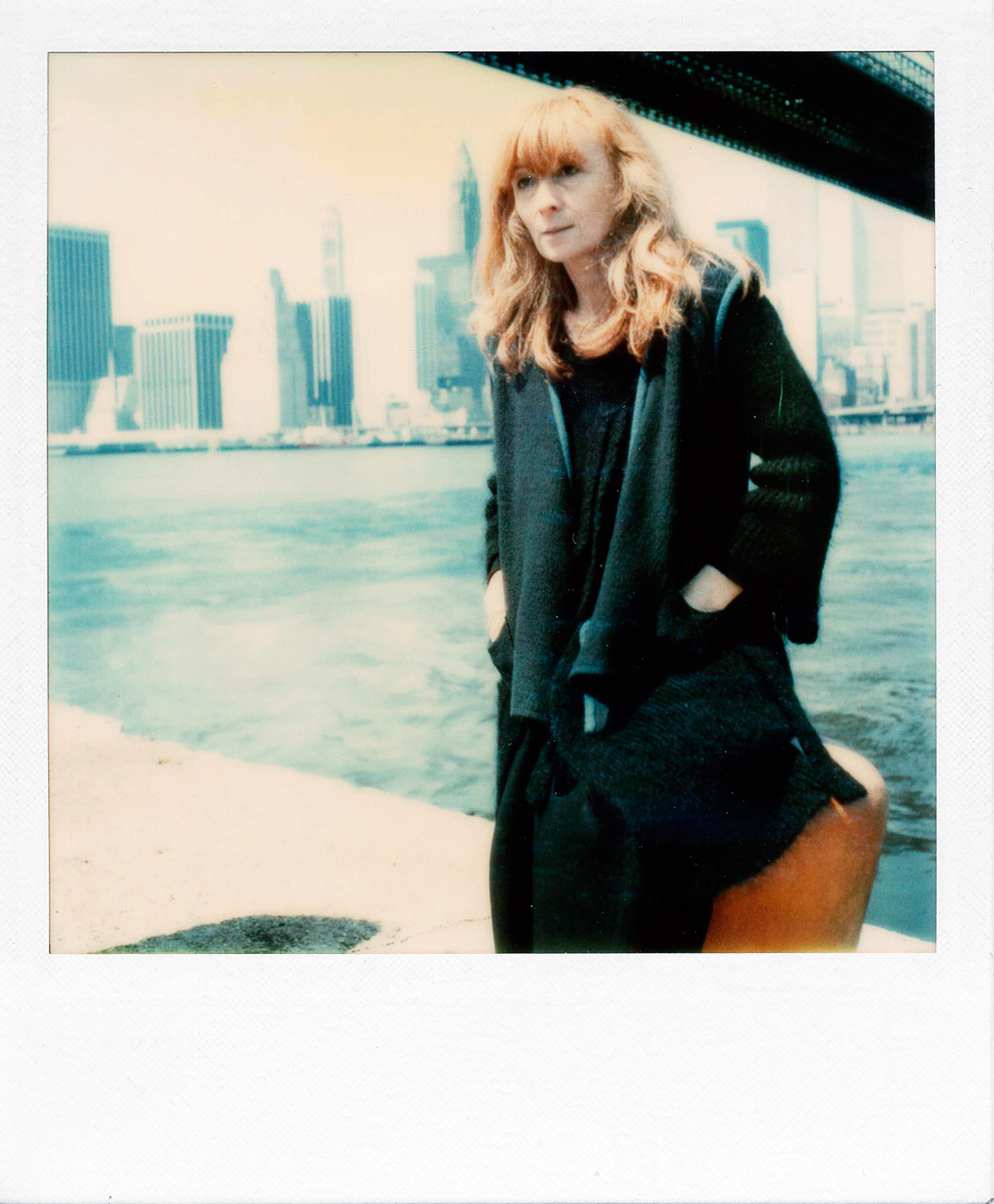

Sonia Rykiel

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM and CAMILLE BIDAULT-WADDINGTON

personal photos of SONIA RYKIEL

SONIA RYKIEL is a wonderful woman — all of Paris loves her. In the past year we’ve seen intense publicity surrounding the 40th anniversary of her fashion house, yet Sonia herself REMAINS A MYSTERY. My friend, the stylist Camille Bidault-Waddington spends a lot of time working with Sonia, so she and I thought that together we might succeed in painting a revealing portrait of this iconic French designer.

PURPLE — A journalist once wrote that you were an “ungraspable woman.” What did he mean by that?

SONIA RYKIEL — I’d written a book that began with the phrase, “I am ungraspable, ungrasped, I roam … I open the ranks of restless women.” That was in the first book I wrote, called And I Want Her Naked… [Et je la voudrais nue……