Purple Magazine

— S/S 2017 issue 27

Théodore Fivel

interview and portrait by OLIVIER ZAHM

Théodore wears a yellow strike sweater and denim vicious pants CARHARTT WIP

Théodore wears a yellow strike sweater and denim vicious pants CARHARTT WIP

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’ve gone through several stages in your work to arrive at a very specific abstraction. I’ve seen performances and collective actions of yours where you’ve physically embodied your work.

THÉODORE FIVEL — I’ve always believed in the idea of total art. That’s why I’ve done video, music, and performances. I’ve also done a bit of fashion, with people you know, people who were pretty contemporary at the time: Vava Dudu, ThreeASFOUR, all those designers — some of whom are still around and have kept the faith. They were pals I’d grown up with, people I met in the late ’90s, back when I met you, when I started going out and understanding what the art scene was all about.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Can we speak of a Paris underground?

THÉODORE FIVEL — Yes. It was underground Paris at the time. I was 20 and had no credentials other than my driver’s license. And what happened? I met some people. And my whole life took shape through various extraordinary encounters. Today, now that I’m older, I no longer know where the underground is. That’s why I’m focusing on sculpture. Total art is on hold.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why speak of total art?

THÉODORE FIVEL — Why total art? Because at age 20, I was bouncing off the walls with energy. I was doing music, doing performances, doing videos. I was extravagant and dressing like a prince every day. For a time, my performances consisted of dressing up, going out onto the street, and letting people trash me, laugh, smile, make fun. That’s what fed my creativity. That total art stuff — I really believed in it. It’s a bit passé and ridiculous now. And then I met Rita Ackermann and moved to New York to join her.

OLIVIER ZAHM — For a long time, you refused to call yourself an artist, didn’t you?

THÉODORE FIVEL — I refused to call myself an artist for many years because it was much cooler, until I met and fell in love with your friend, the painter Rita Ackermann, who introduced me to a new way of envisionning life and told me to get down to work. I got down to work because of my admiration for her.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why did you move back to Paris?

THÉODORE FIVEL — I came back to Paris because I am Paris. I mean to defend French heritage — not out of conservatism, but for the city’s intellectualism. A lot of people spit on Paris, but I don’t give a damn. I adore this city, and it’s my city. I was born in the center of Paris. My mother was a gangster, and my father a provincial, exiled to the center of Paris. He lived in a house on the Left Bank; my mother lived on the Right Bank, and so I had a bridge to cross when I went from one to the other. They lived together for 10 years. An extraordinary life. I’d barely been born when they separated. I had a lovely childhood on the streets. I wanted to come back to Paris to make a film that mixed dance with music, monumental sculptures, and the architecture of Les Halles [the old central market] of my childhood, before it was destroyed. It’s a neighborhood I’d grown up in. I never did make the film, but it gradually transformed itself into sculptures.

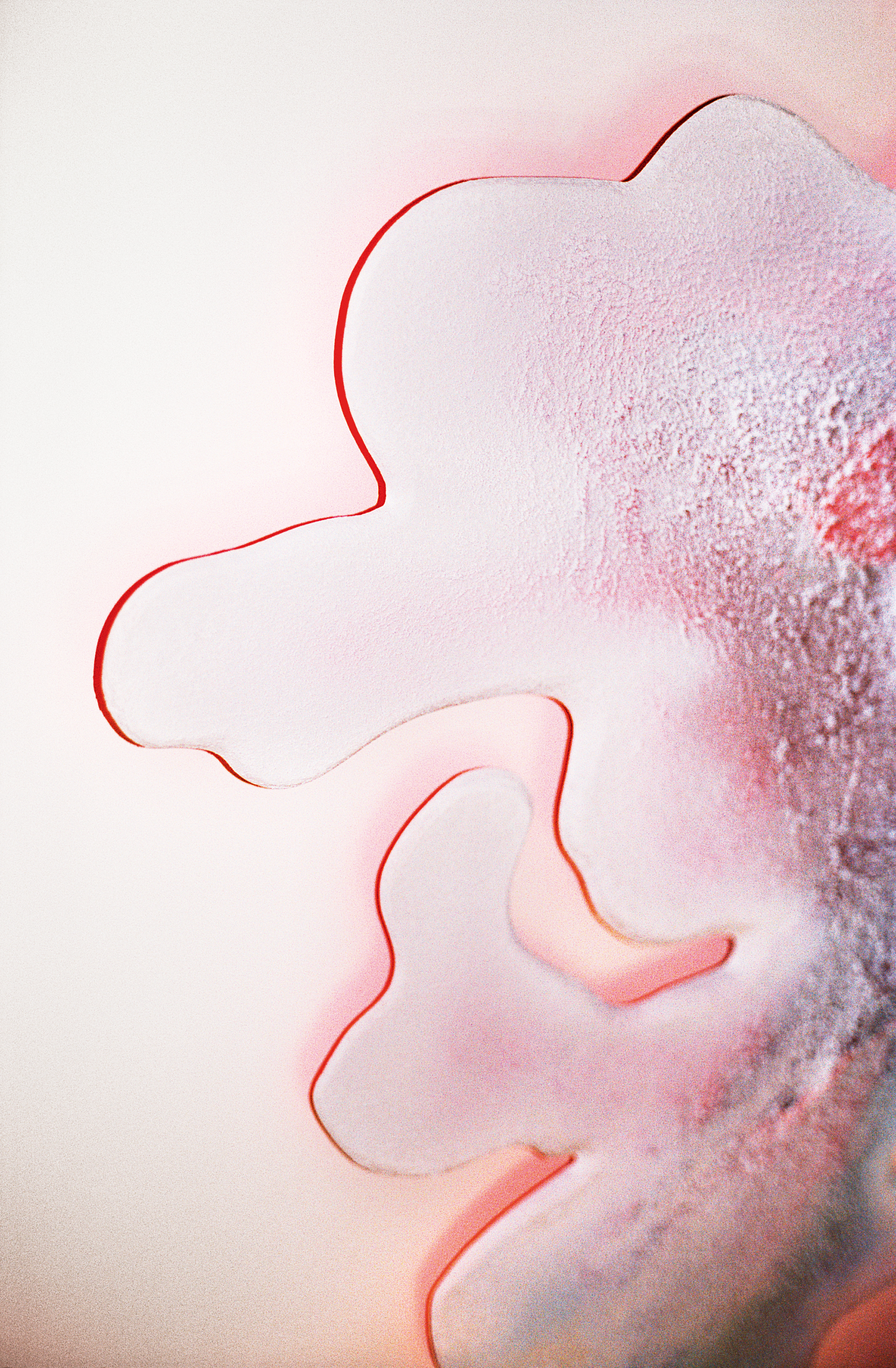

OLIVIER ZAHM — How would you describe your sculpturepaintings?

THÉODORE FIVEL — They’re operas of matter. I feel close to artists like [Jean] Dubuffet and his Phenomena series, for example. Yves Klein would make lunar landscapes which I discovered later ressembled my work a lot. I speak of “operas of matter” because I find that every day they open a new door for me and give me a new take on matter.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s no canvas or frame. It’s wood.

THÉODORE FIVEL — No. They’re sculptures!

OLIVIER ZAHM — Then there’s a layer of paint.

THÉODORE FIVEL — A “charge.” I call my paintings “charges” because painting is charged. That’s what gives it that thickness and volume and relief, with different textures, depending on the series.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And the painting itself looks more like automobile paint or a body-shop paint job.

THÉODORE FIVEL — My first studio was in a squat when I was 17, in a former auto-repair shop with paints in it, extraordinary colors from the ’60s of a kind I’ve never seen again. I think I got myself thoroughly intoxicated at the time, but there were 200 cans of paint with incredible colors. And I did some sublime paintings with it that I’ve since lost when I moved to Arizona to live in Arcosanti, in that experimental town of Paolo Soleri’s, a kind of ’70s myth that’s still struggling along.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So they’re hybrid objects, between painting and sculpture.

THÉODORE FIVEL — For me, they’re sculptures because there’s a volume that I work on, because I work with matter. I’m not ready yet for painting. Painting is the most powerful medium. I’m 40 years old, and when I have a brush in hand and see a canvas, I just shit myself! Painted sculptures are my way of approaching painting.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In spite of everything, you’ve preserved some kind of figuration in your work.

THÉODORE FIVEL — It depends on the colors. If I use black, it looks like the night sky. If I use blue, it looks like the sea. If I use coppery brown, it looks like the ground.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s abstraction, but you also convey something oneiric and geographic.

THÉODORE FIVEL — Literal geography doesn’t interest me, but operas of matter are new worlds, maps of worlds that don’t exist.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What are your sand paintings?

THÉODORE FIVEL — I did several large installations with tons of sand that I would paint with a paint gun. People couldn’t understand what I was doing. It was so surreal that they couldn’t resist touching the things, and that would instantly destroy the installations because sand is hard to set.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You follow an impulse. Your work isn’t a completely calculated thing.

THÉODORE FIVEL — Intellectually I’m pretty naive. I’m very conceptual, but in a naive way. I think that the strength of creativity is close to Picasso in his naive children’s drawings. Truth lies not in pure abstraction, but in naiveté. I’m not talking about naive art or raw art, although those are movements that speak to me and that I’ve taken an interest in.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s much more calculated than naive art or raw art. And the way you install things is very specific.

THÉODORE FIVEL — That’s where I come back to the intellectual aspect of my work. Everything is thought out. I have a lot of trouble putting it into words because everything is always evolving. As one of my close poet friends used to say, “I’m making an opera that will be finished when my life comes to an end.”

OLIVIER ZAHM — Shades of copper, acidic yellows, metallic blues. These are fairly uncomfortable colors. They’re not stable colors on a clear chromatic spectrum.

THÉODORE FIVEL — Yes. I like colors that unsettle.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I very much like your way of installing things on plywood panels here in your studio, and I like your plinths as well. You’ve never separated things — when you speak of operas, for instance. The presentation of your sculptures is just as important as the sculptures themselves, isn’t it?

THÉODORE FIVEL — Yes, it’s true. A lot of stage design goes into it. It’s a décor. I’ve got a strong sense of stage design. It feeds into the joy I feel in giving and receiving. And in presenting things in nonclassical ways.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I like your opera idea because it feeds into the spectacle, décor, and vibrancy that you’re so at ease with.

THÉODORE FIVEL — That’s my life. My big problem isn’t lack of ambition or lack of means because I always find the means. My problem is the era I’m living in. The people in it have rather small ambitions. In the 1980s or the ’30s or the ’20s, people were hyper-creative and completely free. The battle I’m fighting is the battle for anticonformity, the battle against normalcy, because I see so many colors and forms in this life of ours that the world dazzles and inspires me every day. We’ve returned nowadays to a kind of medieval thing. It’s nuts. I can’t figure out why that is.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I think it’s fear.

THÉODORE FIVEL — It’s true. We’re living in a time of fear. I myself have never been afraid. Even back in school, people were calling me a fag. I was big and odd, and dressing like nobody else.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And how do you see your work evolving?

THÉODORE FIVEL — The evolution of my work is that I spend 12 hours a day in the studio. It’s my sustenance, and it nourishes my work as well. For now, I’m in total osmosis with myself, with my work, and I have no desire to let go. It’s slow but pleasant.

OLIVIER ZAHM — This new solitude of yours is important to you!

THÉODORE FIVEL — Very important. I was spread too thin before. I was traveling too much. The problem today is the constant distractions. After five minutes in front of a computer, I start to go crazy. It’s been four or five years since I’ve been able to look at a computer.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you don’t let yourself get distracted by your telephone?

THÉODORE FIVEL — Yes, of course, but at least I don’t let myself get distracted by my computer because I think there’s no nourishment to be found in that. It was there at one point. We’re actually circling back to the subject of total art. I’m of the generation that had a computer shoved in its face and was told, “With this you can do anything.” And you’d just swallow the line. I got lost in all that. That’s why I’m monomaniacal now. I do nothing but sculpture and have returned to matter.