Purple Magazine

— S/S 2017 issue 27

Chikashi Suzuki

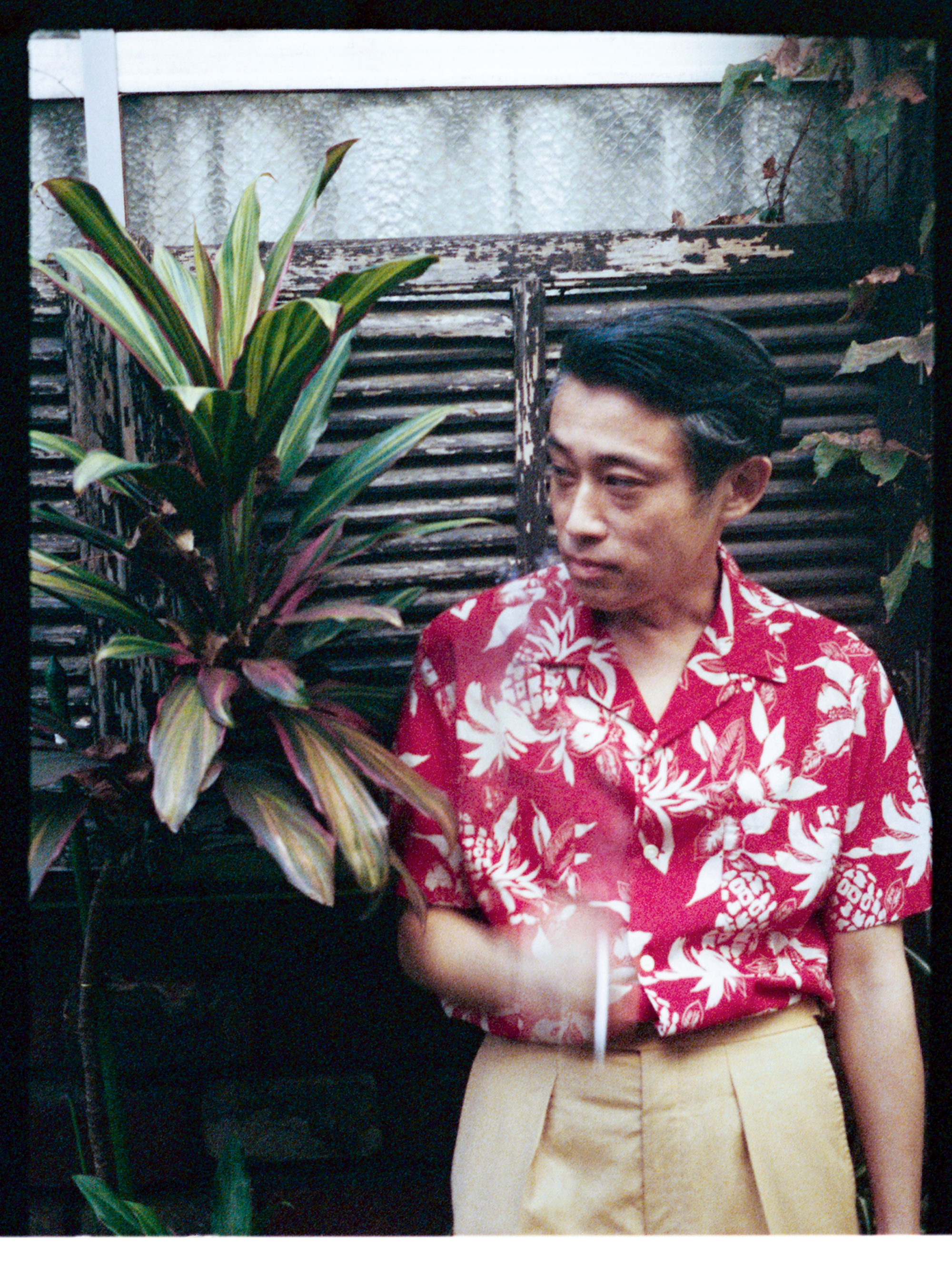

CHIKASHI SUZUKI

photographed by HAJIME SAWATARI

interview by Kazumi Hayashi

Red and ivory Hawaiian hibiscus printed cotton shirt SAINT LAURENT

Red and ivory Hawaiian hibiscus printed cotton shirt SAINT LAURENT

A fashion photographer since the late ’90s, Japan’s Chikashi Suzuki has done photo shoots for magazines such as Purple, Dazed and Confused, and Libertin Dune, and worked on campaigns for Isetan Department Store and various brands, including Toga. His contemporary images express Japan’s beauty, culture, and diversity; he focuses on capturing and collecting key visual elements of everyday Tokyo.

KAZUMI HAYASHI — What made you want to pursue a career as a photographer?

Tell me about the time you went to live in Paris and then returned to Tokyo.

— CHIKASHI SUZUKI — When I was a college student, I went to a group show of artists like David Hammons and Jan Fabre at Watari-um [the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art] in Aoyama. I was…

-

Chikashi’s own white satin Sukajan jacket

-

Beige trench coat STELLA MCCARTNEY over a vintage black silk shirt from BERBERJIN

-

Black and burgundy silk bomber jacket VALENTINO UOMO and brown pants A.P.C.

-