Purple Magazine

— F/W 2010 issue 14

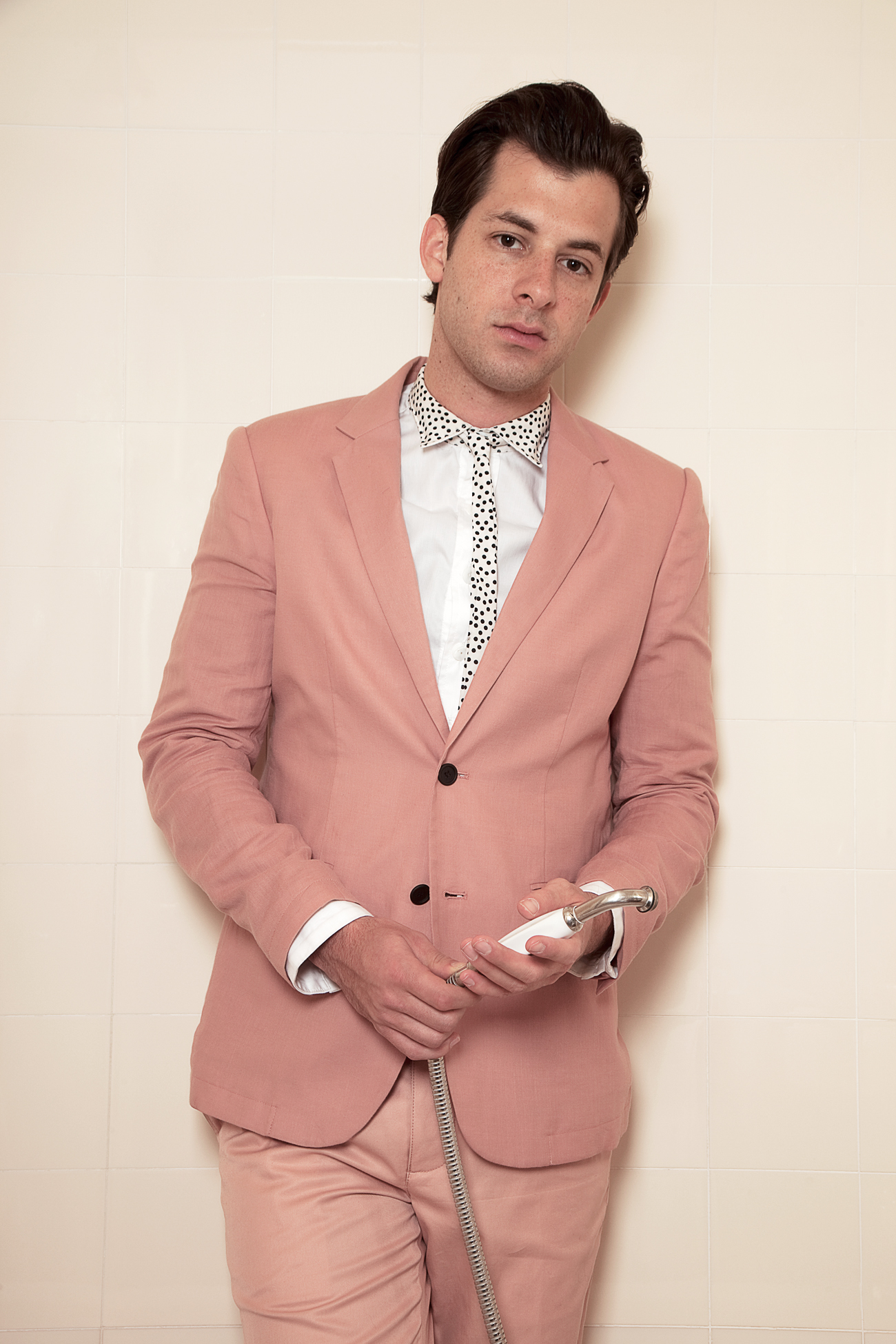

Mark Ronson

White button down shirt with polka dot collar and tie Timo Weiland and peach suit Shipley & Halmos

White button down shirt with polka dot collar and tie Timo Weiland and peach suit Shipley & Halmos

interview by SABINE HELLER

portrait by RICHARD KERN and personal photographs

Frances Tulk-Hart, style — Okima Kilgore, stylist’s assistant

MARK RONSON can evoke a fair amount of jealousy. He’s dark, charming, and sexy: a cross between Jude Law and Paul McCartney. Ronson grew up between London and New York, and hails from Rock nobility : his stepfather, Foreigner’s Mick Jones, wrote the iconic ballad “I Want to Know What Love Is” for Mark’s mother, Ann Dexter-Jones, who found her own fame entertaining famous friends at her wild parties. Robin Williams and Michael Jackson both popped up in Mark’s childhood. Over the past few years Ronson has morphed from celebrity DJ into one of the most talented young producers in music today. He’s worked with Lily Allen,…