Purple Magazine

— S/S 2011 issue 15

Peter Doig

View of Saut d’Eau, north coast of Trinidad, 2010

View of Saut d’Eau, north coast of Trinidad, 2010

Victoria Miro Gallery, London

Victoria Miro Gallery, London

Peter Doig in his studio, Port of Spain, Trinidad, 2003

Peter Doig in his studio, Port of Spain, Trinidad, 2003

Outside his studio

Outside his studio

Down by the River, 2004 oil on linen, 41.2 x 31.3 cm

Down by the River, 2004 oil on linen, 41.2 x 31.3 cm

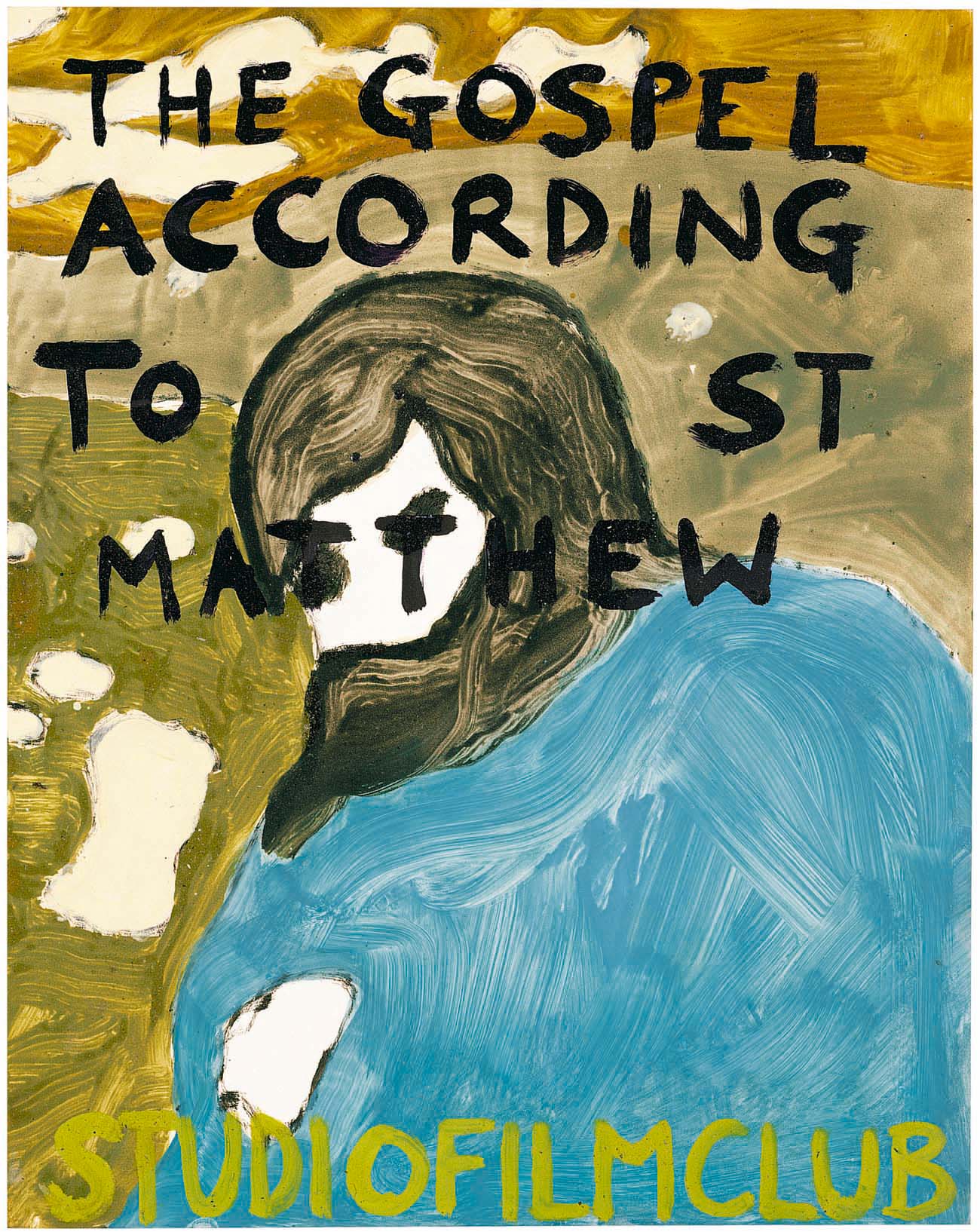

The Gospel According St. Matthew (StudioFilmClub poster), 2004 oil on paper, 72.8 x 57.5 cm

The Gospel According St. Matthew (StudioFilmClub poster), 2004 oil on paper, 72.8 x 57.5 cm

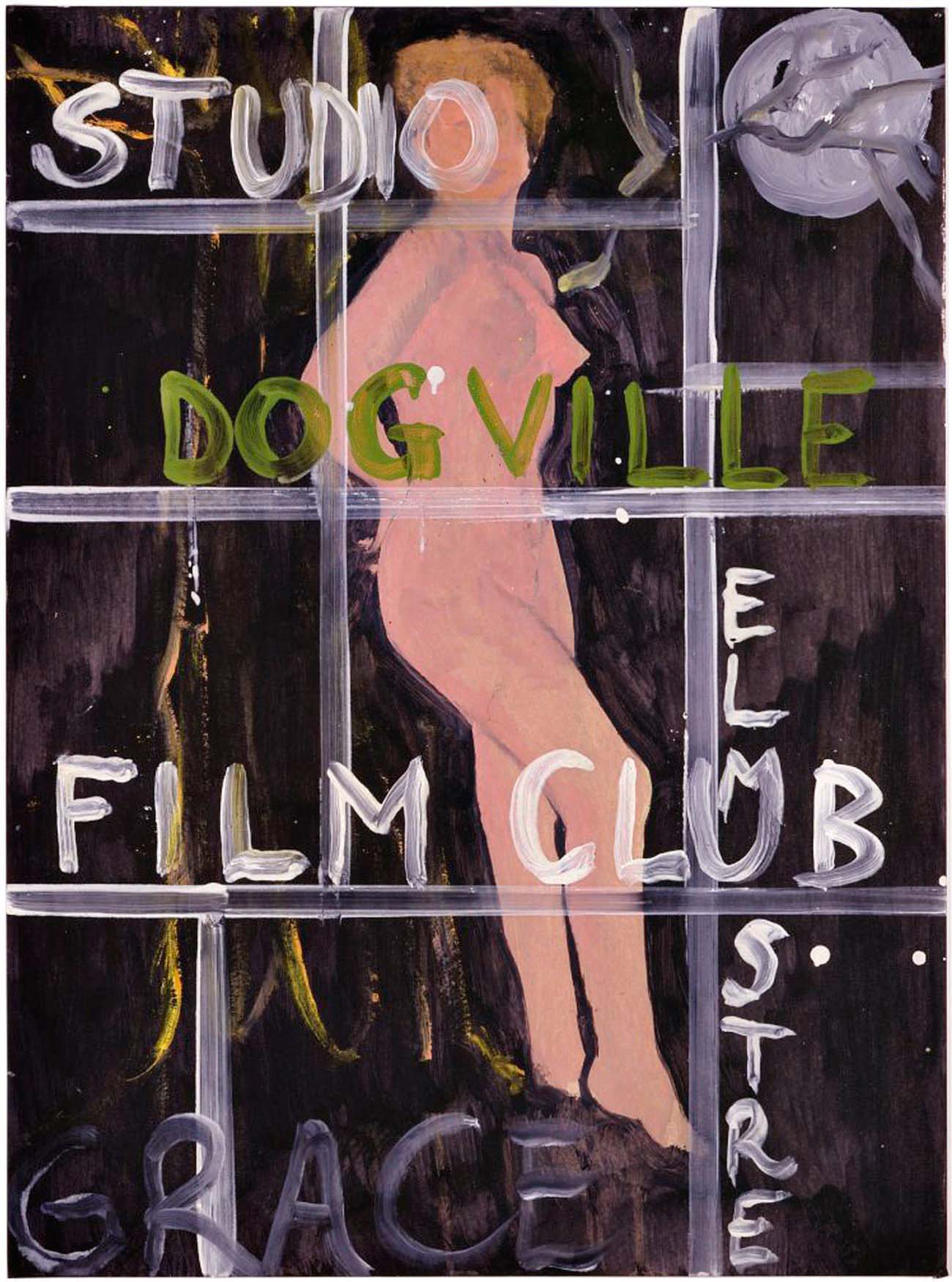

Dogville (StudioFilmClub poster), 2005, oil on paper, 76 x 55.9 cm courtesy of the artist and contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Dogville (StudioFilmClub poster), 2005, oil on paper, 76 x 55.9 cm courtesy of the artist and contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Paris is Burning (StudioFilmClub poster), 2006, oil on paper, 68.7 x 50.7 cm courtesy of the artist and contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Paris is Burning (StudioFilmClub poster), 2006, oil on paper, 68.7 x 50.7 cm courtesy of the artist and contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Concrete Cabin II, 1992, oil on canvas, 200 x 275 cm, courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery,…

Concrete Cabin II, 1992, oil on canvas, 200 x 275 cm, courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery,…