Purple Magazine

— The Paris Issue #31 S/S 2019

chantal crousel

chantal crousel

interview by JÉRÔME SANS and OLIVIER ZAHM

photography by OLIVIER ZAHM

a gallery that has introduced artists from

every part of the world to parisians since the

eighties, and always holds its opening dinners in

chantal’s apartment — where art is not about

decoration but about discussion

OLIVIER ZAHM — How would you describe the development of the gallery scene in Paris over the past few years?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — I’ve been on the Art Basel Miami selection committee for the past five years, and every year I continue to fight against the negative biases that still exist about Paris. It’s as though Paris weren’t up to snuff with the major contemporary art capitals of the world, which is completely false. Paris is still a major hub, with many resources and cultural offerings for people who know about literature and cinema. It’s true that contemporary art has taken longer to assert itself in France, but now things are different. As a teenager, for me, Paris used to be the city of cinema. New Wave film did a lot to make Paris seductive.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You haven’t opened other locations in New York, London, or Shanghai, as many of your colleagues have done. You’ve decided to remain Parisian.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — It’s a personal choice. When my son Niklas [Svennung] takes over from me, he can do as he pleases, but for the time being, he’s as cautious as I am. We’re on the same page about this. Paris remains a center of inspiration and an increasingly more interesting place for contemporary art. We saw this with FIAC [the International Contemporary Art Fair] this year, which definitely surpassed Frieze and approached Art Basel through its offerings and the exhibitions organized across the city, which made it a hundred times more interesting as an event than Basel. If museums and private or public institutions in Paris continue to complement and collaborate with us private galleries, then Paris will be the most beautiful place for contemporary art. We just need to make this known. Artists all over the world will realize that Paris cannot be overlooked — even though we don’t always have the same financial means as those enormous American, German, or English galleries. I believe in Paris and remain loyal to it!

OLIVIER ZAHM — What was your first impression when you arrived in Paris in the 1970s as a student from Brussels?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — During the first 10 years I lived in France, I felt like the sky was the limit. Because I didn’t know anyone, I would go to cafés to learn about people, get a feel for the atmosphere, see how people behaved with each other. Even though I had lived in Brussels for a few years, I needed to get street-smart. One thing that struck me was that here, when I met someone, they’d look me up and down — to see how I was dressed.

JÉRÔME SANS — When did you start your gallery?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — Forty years ago!

JÉRÔME SANS — The art market wasn’t the same as it is now. At the time, it was a completely crazy life choice to become a dealer, like trying to explain something in a foreign language. The business is entirely different now.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — But it’s first and foremost a passion! Before being a market activity. I got into it sort of by chance. My first adventure as a dealer was when I founded the gallery La Dérive [The Drift] in 1976 on the Rue des Saints-Pères with the man I loved. I was just out of school and had met Jacques Blazy, the great specialist in primitive and pre-Columbian art. He made major contributions to the collections at the Quai Branly. We were both young, attractive, enthusiastic, and we got along very well. So, we thought, “Why not go into it together?”

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was the atmosphere in Paris in the 1970s as liberated as people say?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — At the time, there were very strong personalities in the cultural sphere. Françoise Giroud, for instance, was the Secretary of State for Culture. There was Pontus Hultén, the first director of the Centre Georges Pompidou, who became my friend and accomplice. I had done some research, at my school’s request, on the opening of the Centre Pompidou, which was slated to take place in 1977. I saw him at a restaurant, threw a pack of sugar at him, and asked, “Are you Pontus Hultén?” in Swedish. He answered, “Yes, give me your phone number.” So, we traded numbers. Pontus Hultén had a wonderfully free way of thinking. He died about 10 years ago, unfortunately. He came to see the first exhibition of Alighiero Boetti in France, which I organized at my gallery in 1981. Very few people were interested in it at the time. And yet his work is very elegant, very refined.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you find Paris in the ’70s, as someone from Brussels?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — It was the turbulent time of Nouveau Réalisme [New Realism], which I discovered immediately when I arrived in Paris through the exhibition held at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grand Palais. Pierre Alechinsky, one of the members of CoBrA, removed his paintings because he was in disagreement with the content of the exhibition. This movement fascinated me! I decided to study its work for my thesis. That’s why one of the first exhibitions I organized at my gallery was devoted to Christian Dotremont, a year before he died. I presented a selection of his “logoneige” photographs, those logograms he made in the snow in Lapland, Finland. In fact, that’s where the title of the book we’re preparing for the 40th anniversary of the gallery comes from, Jure-Moi de Jouer [Promise Me You’ll Play]. It will be out next year.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, your gallery had a political leaning, though not militant per se. Is this still the case today?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — My gallery is both political and poetic, in the sense that in art, humankind, people, and the “other” are at stake. That’s been my motto since the beginning. This sensitivity to mankind perhaps comes from my Belgian origins. I find it in Marcel Broodthaers, who also has Belgian roots. But also in contemporary artists like Oscar Tuazon, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Thomas Hirschhorn — artists that Purple is fond of.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, you were struck by the CoBrA movement as a teenager.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — Yes, absolutely. When I was writing my thesis on CoBrA, I would visit Christian Dotremont in Brussels often, during his last few years. The CoBrA movement was fascinating, very active and international. The CoBrA journal was addressed to artists across the world who were in dialogue. Among them were African artists, Cubans, Americans, Germans, French artists… And Asger Jorn, of course, who is still underappreciated in France, in my opinion. His work was multidisciplinary, combining different modes of expression, including writing and painting, détourné images. He was a very engaged artist, tied to the Situationists. At the end of CoBrA, the movement had become so diverse that friction was inevitable between people whose work had evolved in different directions since they’d first met. At the time, Jorn was becoming interested in ceramics and the Situationists, and he decided to move away from CoBrA. He moved to Albisola, in the north of Italy, and worked with Piero Manzoni and Lucio Fontana on his ceramics projects, which was the really the birth of a very important school of ceramics in Europe.

JÉRÔME SANS — Which other artists did you exhibit at the time?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — An artist who is very important to me, but with whom I only held one exhibition because he was in prison — a South African artist, Breyten Breytenbach. He was also a very gifted writer. He was imprisoned for having married a French woman, originally from Vietnam, during apartheid, when mixed marriages were prohibited. He was a communist. He went to jail, and his wife was sent off to the Netherlands. He would only be freed on the condition that he stopped painting. The exhibition came at an important time for the gallery. I discovered him in a gallery in Amsterdam and had all his paintings shipped to Paris. I obviously didn’t sell any of them! I also did a few exhibitions in my apartment, where I showed the work of Jean-Luc Parant, for instance, a really incredible exhibition: 400 balls were brought into the empty living room through the window. It was fantastic. But the first artist who really brought some attention to the gallery was the English artist, Tony Cragg, whose first exhibition I held in 1980. An extraordinary exhibition. He came in very nonchalant and worked with objects he’d collected on the street. Every night, we’d go out in my Volvo and drive around Paris, right before the trash collectors made their rounds. He’d say, “Stop, I want that.” For four days, things piled up in the gallery. Tony Cragg would collect everything the city of Paris had thrown away, assembling it into a perfect, geometric form. On the eve of the opening, he worked all night, and the chaos became orderly. It was absolutely incredible.

JÉRÔME SANS — It also testifies to the spirit of the time. Today, before a project has even been conceived, most artists ask, “What’s the production budget?” At the time, you could work site-specifically, and artists often arrived nonchalantly, as you say, ready to work on the spot.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — It was a fascinating time, a crucial moment. With a real intellectual drive. I still have journals from the time, like Guy Debord’s Situationist International. The critic Bernard Lamarche-Vadel played an important role in showcasing the work of an entire generation of French and foreign artists. For your generation, too, I think… It’s thanks to him that I got interested in the first artists I showed in the gallery at the Rue Quincampoix. Even though no one was into them at the time.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you feel avant-garde, pioneering?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — I wasn’t thinking about that. I wanted to show things that no one had seen in Paris before. Because I wasn’t French, I didn’t want to do what a Parisian gallery was doing because I didn’t know the Parisian scene well. I knew CoBrA better, the history of Belgian art, and what I had seen at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent when Jan Hoet was the director.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’ve been breaking down barriers your whole life. Contemporary art in France, despite the new Centre Georges Pompidou in 1977, and Pompidou’s own passion for geometric and kinetic art, was still too new for the Parisian bourgeoisie.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — Yes, perhaps. That’s why Ileana Sonnabend’s gallery, which opened in Paris with a high-quality international program, unfortunately had to close. She was selling only to German and Belgian collectors, but nothing sold in France. Paris still remains a major center, despite it all. An international meeting place. In the ’70s, I did an internship, as part of my studies, with the great art dealer Alexandre Iolas for about six months. It was amazing! He had a global perspective on the world! He worked with Greek artists, with Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint-Phalle, the Surrealists, Max Ernst, Victor Brauner — incredible artists from all over. He had a few enlightened collectors like Jean and Dominique de Menil, some of his most important clients, who opened their own foundation in Houston at the time. They had a real eye and a rare sense of the times. I never worked in an environment that felt limited to a French perspective.

JÉRÔME SANS — But at the time, at the beginning of the 1980s, Paris was behind Germany, Italy, and especially New York, despite its flamboyance. That Bermuda Triangle…

CHANTAL CROUSEL — And the British. Apropos, I discovered Tony Cragg in Ghent, while Jan Hoet was preparing the exhibition “Art in Europe after ’68” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, which was an “eye-opener,” as they say. This exhibition brought together all the tendencies that were emerging in European countries. Tony Cragg was part of that post-Henry Moore generation of British artists, a reaction against Moore. Now, Tony Cragg has become today’s Henry Moore — even though his work really marked a moment of change.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What did he have against Henry Moore?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — He was a formalist sculptor. Bruce McLean, a performance artist I met through Tony Cragg, had done a performance that consisted of drinking soup, with miniature sculptures by Henry Moore, onstage. At the beginning of the 1980s, a real desire for a break with the previous generation was felt in a number of different countries.

JÉRÔME SANS — In England, this was the “Young British Artists” generation, which included Anish Kapoor, Richard Deacon, Antony Gormley, Shirazeh Houshiary, Bill Woodrow…

CHANTAL CROUSEL — Yes, and Barry Flanagan, with his incredible soft sculptures, or Bruce McLean, who became a designer. There were also the Junge Wilde (Wild Youth) in Berlin and the Mülheimer Freiheit in Cologne with Jiri Georg Dokoupil, Walter Dahn…

OLIVIER ZAHM — I loved Dokoupil. He really attacked painting.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — Fantastic! He did an exhibition at the Place du Tertre with daubs that represented famous Parisian monuments. It was his second exhibition, and it was beautiful, with those very thick, impastoed paintings. We did two or three exhibitions together. He was showing with Juana de Aizpuru in Seville. That whole group of artists had only one dream, which was to buy a house in the south of Spain. They were all attracted to this village near Seville, Carmona, and wanted to hide away and live there discreetly. And let’s not forget New York! The generation of Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo, which I exhibited in 1982 and called “Picturalism.” A group of artists … students of Robert Filliou and John Baldessari, for the most part. Things were happening all over the place in the ’80s. In Italy after Arte Povera, a new generation was emerging — around Pino Pinelli and a few other artists like Irma Blank — which is just starting to resurface.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you keep going as a young gallerist in Paris without any money, in a city that was just then beginning to discover contemporary art in the mid-’80s?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — I didn’t have a choice. I wanted to keep moving forward. It all happened step by step. At the very beginning, there were documenta and the Venice Biennales, which all the young artists I was showing were part of, and I’d discover others, so I couldn’t really stop or go backward. There was only one way to go: forward, to keep moving with the artists, to get them discovered. Once again, my gallery was in Paris, and even though I am not French, I sometimes understood the French better than they understood themselves. I was acting as a mediator, translating for the French — who often didn’t speak any other language — what other artists were doing and explaining to foreigners what the French were doing.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What about French artists?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — There were a few. For instance, I organized the first exhibition for Sophie Calle, whom I met through her father Bob Calle, a big collector. I exhibited her work very early on. She had shown me her notebooks full of Polaroids, with the stories of her stay in an unoccupied building that she was squatting and which was undergoing repair near the Quai Branly. That was really the beginning for her. In that chic neighborhood, it was a kind of infiltration. There were unexpected things happening behind that very conventional, bourgeois facade.

OLIVIER ZAHM — At the end of the 1980s, your gallery was well established and well known. It held its own, distinct from other French dealers at the time, like Yvon Lambert.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — I still needed a little push. In 1983, for example, I had some health problems and spent a month in the hospital. Ghislaine Hussenot came in at that moment and asked if she could join the gallery because she wanted to learn. We became partners for five years. We did some beautiful exhibitions together and had a great program. After five years, we separated, and then Ninon Robelin, who ran the great gallery BAMA, asked me, “What’s it like to work with you?” I really liked the artists Ninon was showing. At La Dérive, I had works by Filliou on loan for my exhibition “Signs, Traces, Writings,” which included drawings by Martin Szekely before he became a sculptor and designer. Ninon had just separated from Claudine Papillon, and we got along very well.

OLIVIER ZAHM — If I’m not mistaken, it seems there are a lot of women working in Parisian galleries.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — No, it’s the same in New York, too: Marian Goodman, Metro Pictures, Annina Nosei, Paula Cooper, Sonnabend, Carol Greene…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Would you say that there’s something specific and important about the vision and choices of women in the art world and in galleries?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — I don’t think so. A man at the helm of a gallery can be as sensitive as a woman. But it’s true that in the art world, in order to preserve purity of intention and avoid falling into power plays, the feminine — in a general sense, for men and for women — can play a crucial role. To be an art dealer, you need to have a certain openness and courage, to let yourself take risks and be swept up.

JÉRÔME SANS — You’ve come close to bankruptcy in the past…

CHANTAL CROUSEL — At the beginning of the ’90s! The financial crisis started in 1991 and continued into 1992. Ninon Robelin, my partner at the time, who brought investors into the gallery, left… I started to encounter major difficulties and was really alone, struggling to keep everything going. From one day to the next, I had to reimburse all my debts and pay my artists. The brilliant collector Maja Hoffmann really supported me, as did the German artist Sigmar Polke. That’s also when the artist Gabriel Orozco joined the gallery. A new artistic chapter began. That was the start of a new decade.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your gallery has been at the forefront of changes in art since the early ’90s and is becoming important for my generation. It’s as though at the beginning of the ’90s, you became a new emerging gallery again.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — I’m becoming a young gallery, working under my name and for myself. Just like in the beginning!

OLIVIER ZAHM — But your vocation as an art dealer hasn’t changed, despite the incredible growth in the market and the fact that today, your gallery is quite established and well known.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — That’s also why I have chosen to stay in Paris, rather than expand to all the major contemporary art capitals. As a dealer, my role isn’t only to make sales. It’s not only about selling works of art. I also follow my artists, stay by their side. That’s why, at the moment, I am resistant to the idea of opening a satellite space in New York or China, as many of my colleagues have done, though my son Niklas and I discuss it frequently. Personally, I’m at the stage where, with my experiences and my desire to continue to live as I please, it’s very important that the artists you love can trust you, can continue to count on you. They need to have someone to discuss things with, to talk about ideas and their work. Dialogue with artists is crucial. Especially when they become successful and become the focus of international attention, artists experience enormous pressure to keep producing more work, always more work. An intelligent artist cannot live like that. They need partners to protect them, not a swarm of people asking them to make a new work for such and such an art fair, or satellite gallery or branch…

JÉRÔME SANS — There is a real danger of overproduction fueled by the increase in the number of art fairs and exhibition spaces.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — My convictions remain the same. A work is not interesting if it does not create new points of reference. First, you have to deconstruct certain coordinates in order to create new ones, and each new point of reference propels us forward, opens up a horizon, and allows us to engage with everything that is happening in the world today. We need artists who can announce new things while also denouncing old ones, who enable us to experience who we are, where we live, and what is happening in front of us, in a different language. For these criteria to be activated, an artist has to disrupt things. Either you adhere to the criteria and make a step forward, you grow — or you reject them and shut down or fall into mere lifestyle. I think today’s enemy — far more than social media

— is lifestyle.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What do you mean by “lifestyle”?

CHANTAL CROUSEL — It’s a facade, a display, a decor. It’s offering a simulacrum of culture to people who are too busy, too disinterested, or too insensitive to care about contemporary art. Contemporary art becomes one thing among many others — clothes, cars, houses — that allow people to give the impression that everything in their life is beautiful, harmonious, and smooth. There’s no friction, no obstructions, no questioning.

JÉRÔME SANS — Since the beginning, you’ve distinguished yourself through your hospitality. With your son Niklas, who will carry the torch, you’re still the driving engine. You still embody this sense of transmission, including when you hold dinners after your openings in your apartment. There’s a human dimension, a bond that is created, a real intimacy.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — I ask each artist we have an exhibition with, “Do you want to have a dinner at home or at a restaurant?” and they always choose home. You can speak to different people, move around. People stay as long as they want and spend time with whomever they want. Those who are attending for the first time go on a tour to see what’s hanging on the walls. Some of them are disappointed because I’ve hung primarily small works, which are in dialogue with the light and connect to everything in the apartment.

JÉRÔME SANS — What’s beautiful here is that all the works bear some relation to you. For instance, the collage by Thomas Hirschhorn in your kitchen is a work you bought in 1998. He had installed a kind of market in a public space.

CHANTAL CROUSEL — Yes, they tell my story as a dealer. I travel a lot and am always very happy to be home again. My history is here. I need it all to be in one place.

END

LOW TABLE BY DOMINIQUE MATHIEU, PAIR OF ARMCHAIRS BY PIERRE JEANNERET, 1952-56, FROM CHANDIGARH, COPYRIGHT ADAGP, PARIS, 2019 / VASE NORD BY MARTIN SZEKELY, 1989, PRODUCED BY LA MANUFACTURE DE CRISTAL VAL SAINT-LAMBERT

LOW TABLE BY DOMINIQUE MATHIEU, PAIR OF ARMCHAIRS BY PIERRE JEANNERET, 1952-56, FROM CHANDIGARH, COPYRIGHT ADAGP, PARIS, 2019 / VASE NORD BY MARTIN SZEKELY, 1989, PRODUCED BY LA MANUFACTURE DE CRISTAL VAL SAINT-LAMBERT

DAYBED PK80 BY DANISH DESIGNER POUL KJÆRHOLM, PRODUCED BY FRITZ HANSEN, IN CHANTAL CROUSEL’S APARTMENT

DAYBED PK80 BY DANISH DESIGNER POUL KJÆRHOLM, PRODUCED BY FRITZ HANSEN, IN CHANTAL CROUSEL’S APARTMENT

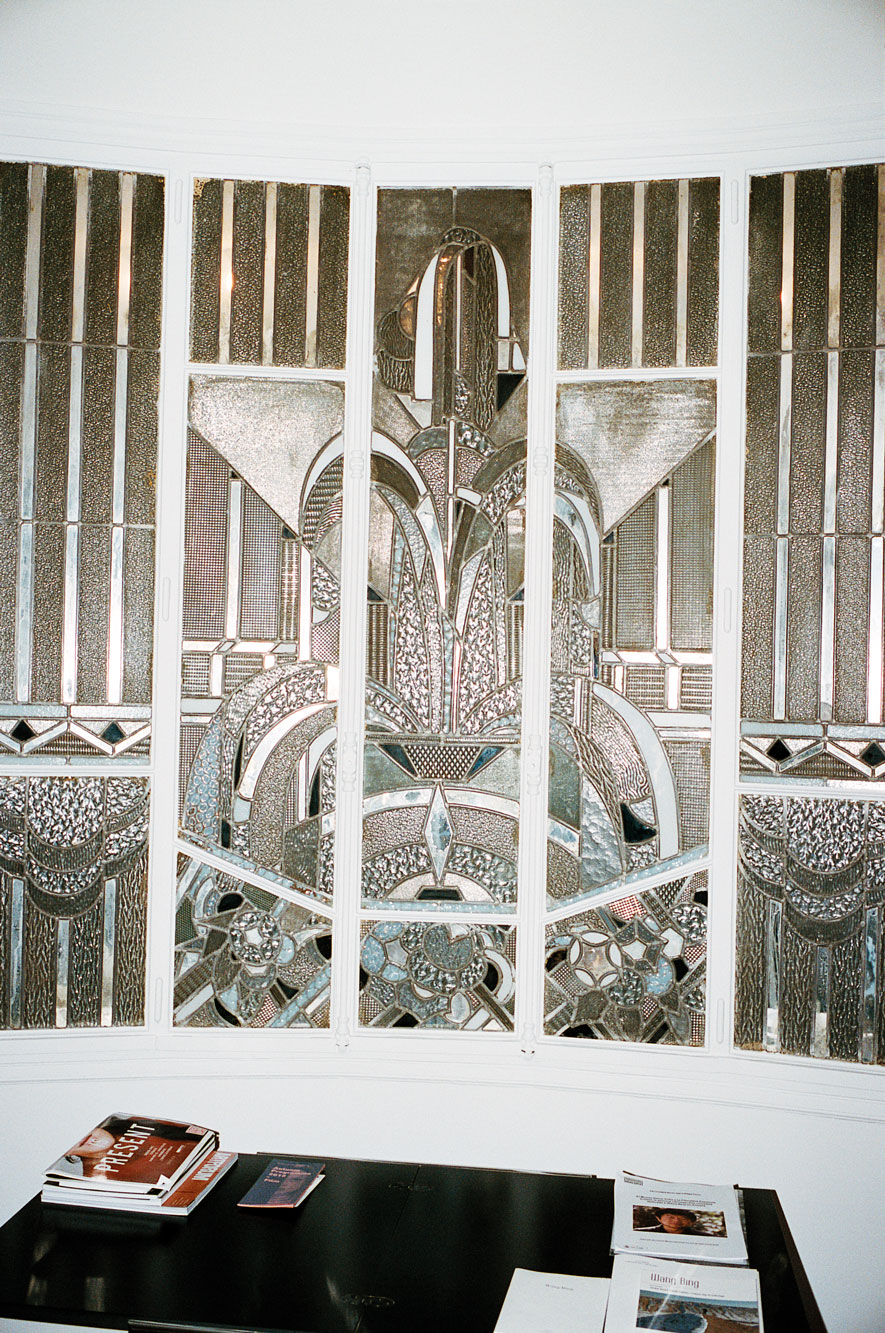

ORIGINAL STAINED-GLASS WINDOW IN CHANTAL CROUSEL’S APARTMENT, 1926

ORIGINAL STAINED-GLASS WINDOW IN CHANTAL CROUSEL’S APARTMENT, 1926

JIMMY DURHAM, RESURRECTION, 1995, COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

JIMMY DURHAM, RESURRECTION, 1995, COURTESY OF THE ARTIST