Purple Magazine

— S/S 2009 issue 11

Terry Richardson’s Life Story Episode 2

Terry and his friend Jon, Hollywood, 1974

Terry and his friend Jon, Hollywood, 1974

Terry and Eric, New York City, 1970

Terry and Eric, New York City, 1970

Terry with his father Bob and Anjelica Huston, Woodstock, New York, 1971

Terry with his father Bob and Anjelica Huston, Woodstock, New York, 1971

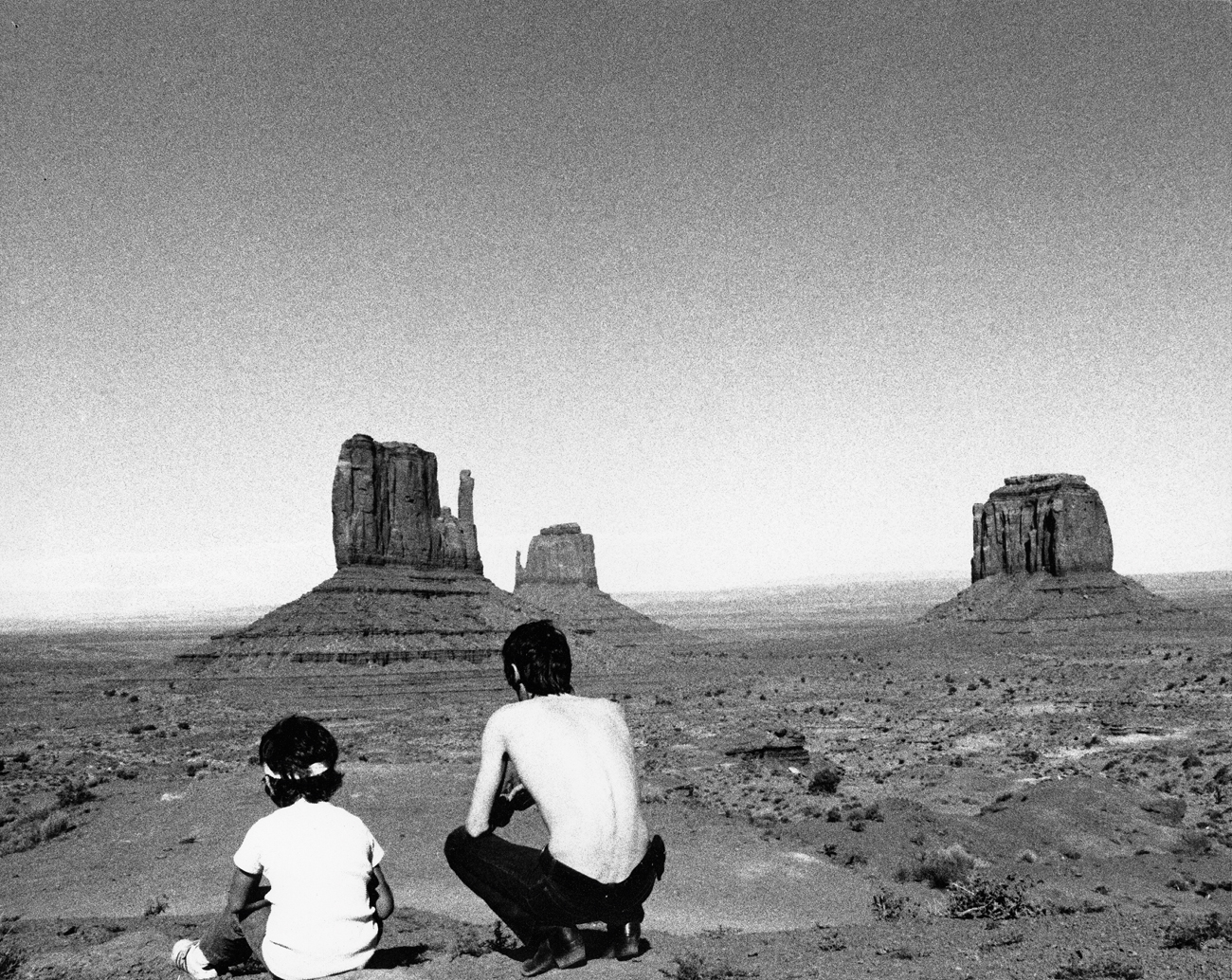

Terry and Jackie, Utah, 1974

Terry and Jackie, Utah, 1974

Terry in Sausalito, California, 1972

Terry in Sausalito, California, 1972

Terry and Emanuelle, Woodstock, 1973

Terry and Emanuelle, Woodstock, 1973

Terry as Billy Jack, Hollywood, 1974

Terry as Billy Jack, Hollywood, 1974

TERRY RICHARDSON’s LIFE STORY

Episode 2

Ages FIVE to NINE

OLIVIER ZAHM — Let’s start with your childhood in Paris, Terry. Your parents lived there for two or three years, right?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Let me see. We moved to Paris when I was nine or 10 months old, and then when I was four years old we moved back to New York, so, yeah, we lived there for three years. French was…