Purple Magazine

— S/S 2009 issue 11

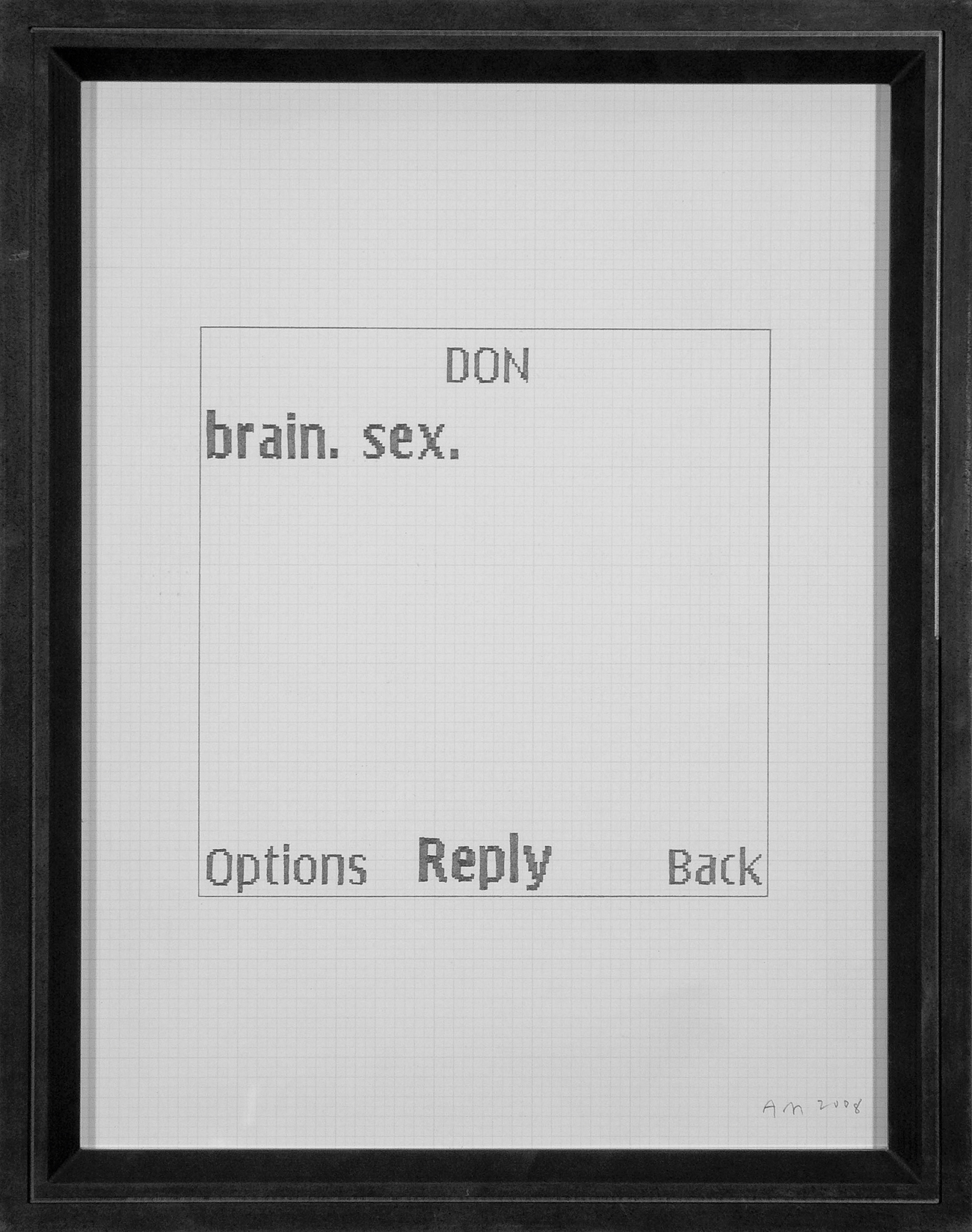

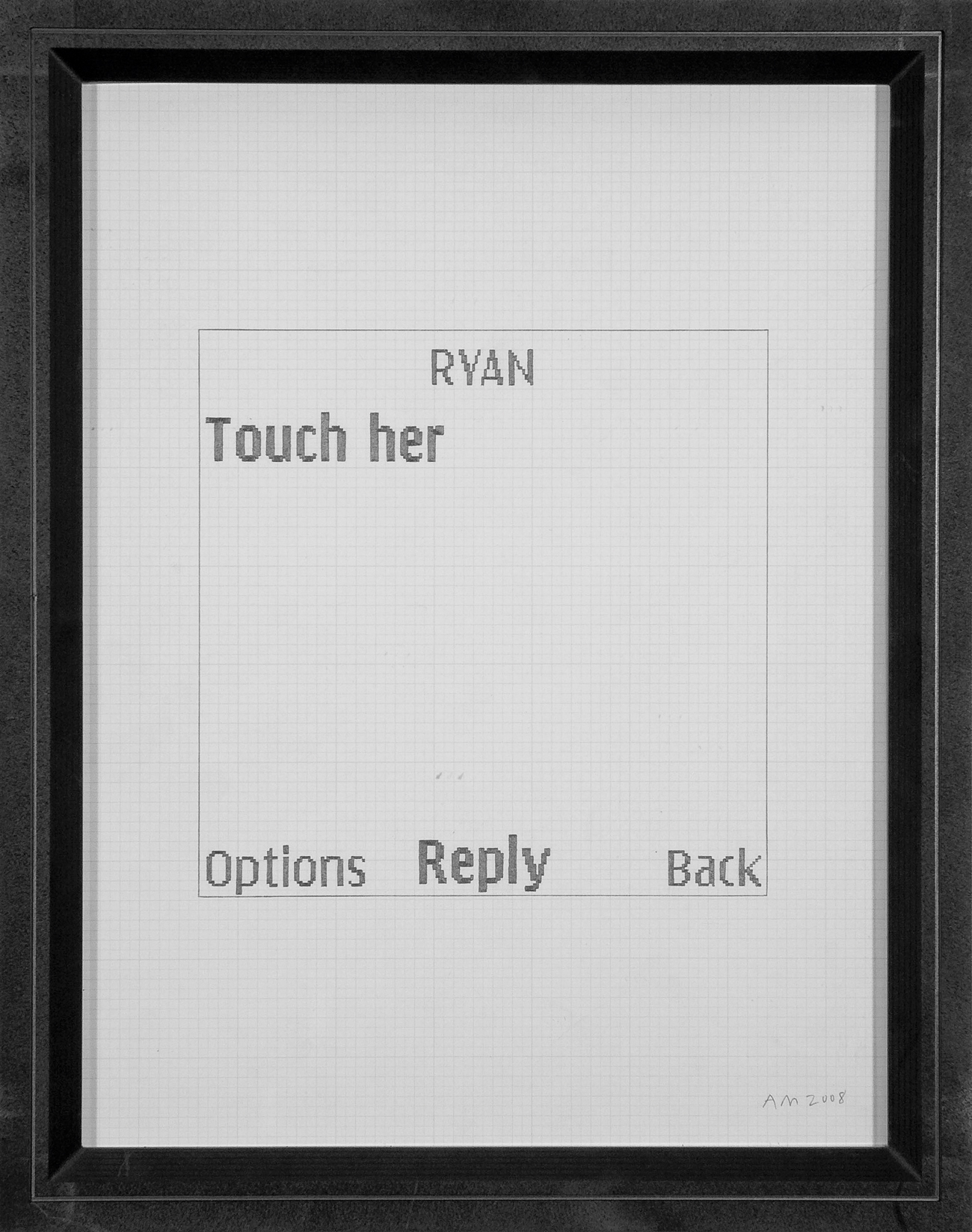

Adam McEwen

text by JOHN MCWHINNIE

The past five years have been good to the art world. Artists, collectors, curators, museums, magazines, and even its critics have earned great bounty. And though anxiety did occasionally plague the art tribe in the past year, a greater sense of euphoria has prevailed. The belief was that the global art market had become immune to the vacillations of other economies. If the Americans dropped out, so the thinking went, the Russians would step up; if the Russians faltered, there were the Koreans; if the Koreans stumbled, the Arabs would pick up the slack; and ultimately if they all swooned, there would always be the Chinese. It was, after all, an art world that was looking increasingly like a polyglot clusterfuck, something along the lines of the orgy scene in Bob Guccione’s Caligula.

In the midst of this spectacle of art lust, trendy art…