Purple Magazine

— F/W 2009 issue 12

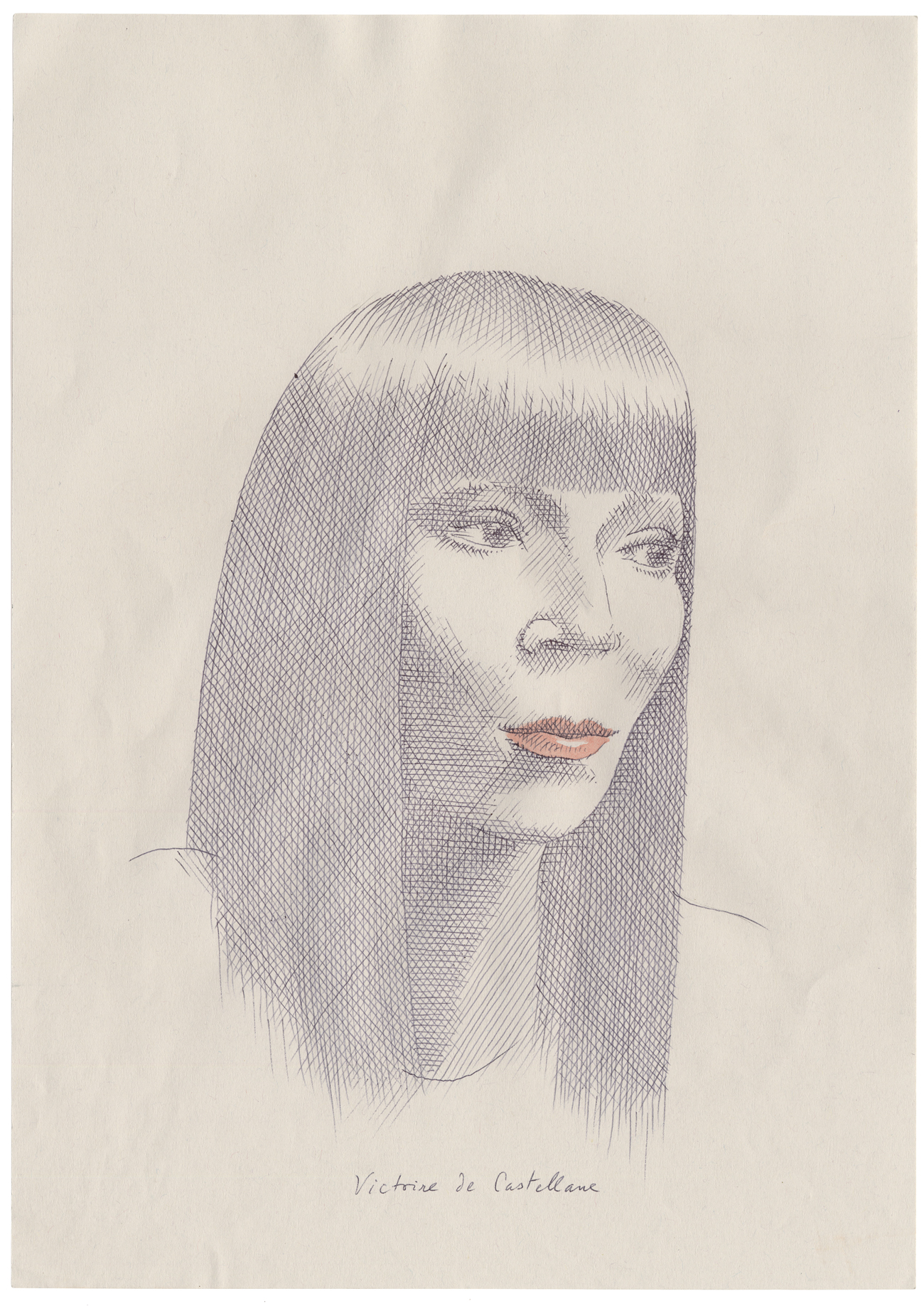

Victoire de Castellane

Portrait by Pierre Le-Tan

Portrait by Pierre Le-Tan

photographs and interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

portrait by PIERRE-LE TAN

On January 1, 1998 Victoire de Castellane, a young woman from an eccentric French aristocrat family, started Dior Haute Joaillerie, reinventing the world of fine jewelery. Breaking all the conventions and overcoming all the restrictions, Victoire introduced explosive colors, amusing fairytales, and personal fantasy into jewelry, taking her inspiration from popular culture, video games, Japanese mangas, custom cars, and erotic fantasies. She introduced the use of precious and semi-precious stones, many long ignored because of their audacious brilliance — gigantic amethysts, huge citrines, and crystalline aquamarines. She repainted gold, creating rose-lacquered gold, translucent purple gold, and ultra-green gold — all in all, nothing less than

a revolution in sense and sensation.

photographs and

OLIVIER ZAHM — You’re seeing a psychoanalyist four times a week? When did this all start?…