Purple Magazine

— S/S 2012 issue 17

Lisa Yuskavage

interview by SABINE HELLER

portrait by JASON SCHMIDT

All artwork images courtesy of Lisa Yuskavage and David Zwirner Gallery, New York

LISA YUSKAVAGE has the skill of an old master, the imagination of a manga illustrator, the naughtiness of a Catholic schoolgirl, and a serious art school education from Yale. Her color-drenched world of hyper-erotic female nudes defies all conventions of beauty, repression, power, and surrender. Amid such paradoxes, Lisa’s paintings resist simple interpretation. I met Lisa at her studio in Red Hook, Brooklyn.

SABINE HELLER — How would you describe your paintings?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Every aspect is imbued with mood or psychological importance. It’s not just the figures. Each character and each element add characteristics. In Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining, when the camera follows the little boy down the hall and he stops, the camera keeps going. The camera isn’t tracking the boy — it’s got a mind of its own, which is spooky. In The Shining, a choice creates a psychic experience, and something jumps out of the film into the viewer, in a magical transition. The realization of this opened me up to the idea that everything you do can shift the way things are seen — that formal elements can be rich in their ability to overpower what’s normal. I want an intense experience when I look at art. There’s a difference between a figurative painting that’s illustrative and one that has codes. All paintings illustrate something, but there’s a way to go beyond the picture and add a psychic quality.

SABINE HELLER — Speaking of magic, would you describe your relationship to art history as being like a séance?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — It is like a big séance, like we’re summoning the dead every time we examine old art. I’ve been moved to laughter in a church at a joke Caravaggio made 500 years ago. If you can read the language of pictures, the codes can be translated over time and history, and across language. I’m also amazed that so many people stare at my painting, Triptych, because it’s so different from anything I’ve done.

SABINE HELLER — People are enthralled by the scale and symmetry of Triptych. The view dives deep into a landscape and into a vagina. I love how you identify the characters as ego, super-ego, and id.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I have no idea how I did it. The painting was a way of finding order out of chaos. It might be a one-off. It’s almost like not knowing what you look like, and then someone shows you your face, and you look gorgeous. I don’t know if I can do that again — intentionally, I mean.

SABINE HELLER — It’s not exactly like you did it intentionally the first time. You started a journey without knowing where it would lead. As you’ve acknowledged, you were playing Exquisite Corpse, except that you were the only one playing.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I’m an intuitive artist. People sometimes assume I operate with a manifesto, but it’s not true. What was interesting about Triptych was that I viewed my discovery process as a strength, rather than a weakness. I couldn’t believe how the painting found itself. Michelangelo said, “The figures are already in the stone — you just have to take away the excess.” I don’t feel like I painted it — I feel like I found it, like it always existed. When I finished it, my husband and I stood back and wondered how it happened.

SABINE HELLER — Is your husband Matvey Levenstein involved in your work?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Matvey and I have painted side by side for 20-something years. We met in 1985 as art students and have looked at each other’s art ever since. As a rule, I look at art more than most people do. I traveled to Europe as a teenager, and I know what art looks like physically. It bothers me when students don’t care about that. I feel like asking them why I should look at their pictures. Why don’t they go put them on the Internet and destroy them?

SABINE HELLER — Your technical proficiency comes through clearly in your work.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — What matters to me is what my paintings look like physically. I don’t feel like a particularly skilled painter. I do what’s needed. I’m just lucky because I live in a time in which most painters are worse than I am.

SABINE HELLER — Even your critics agree that you’re a gifted painter. Why does someone so gifted choose to paint a cartoon-like figure masturbating?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I like it when people say I’m getting away with stuff men can’t get away with.

SABINE HELLER — Men have been getting away with it for hundreds of years. Why the boundaries?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I don’t like biography as a way of understanding art, but there’s something essentially human in what I do. To do my work, I have to be me, exactly the way I am. I don’t always feel talented. If you saw my earlier paintings, you’d know what I mean.

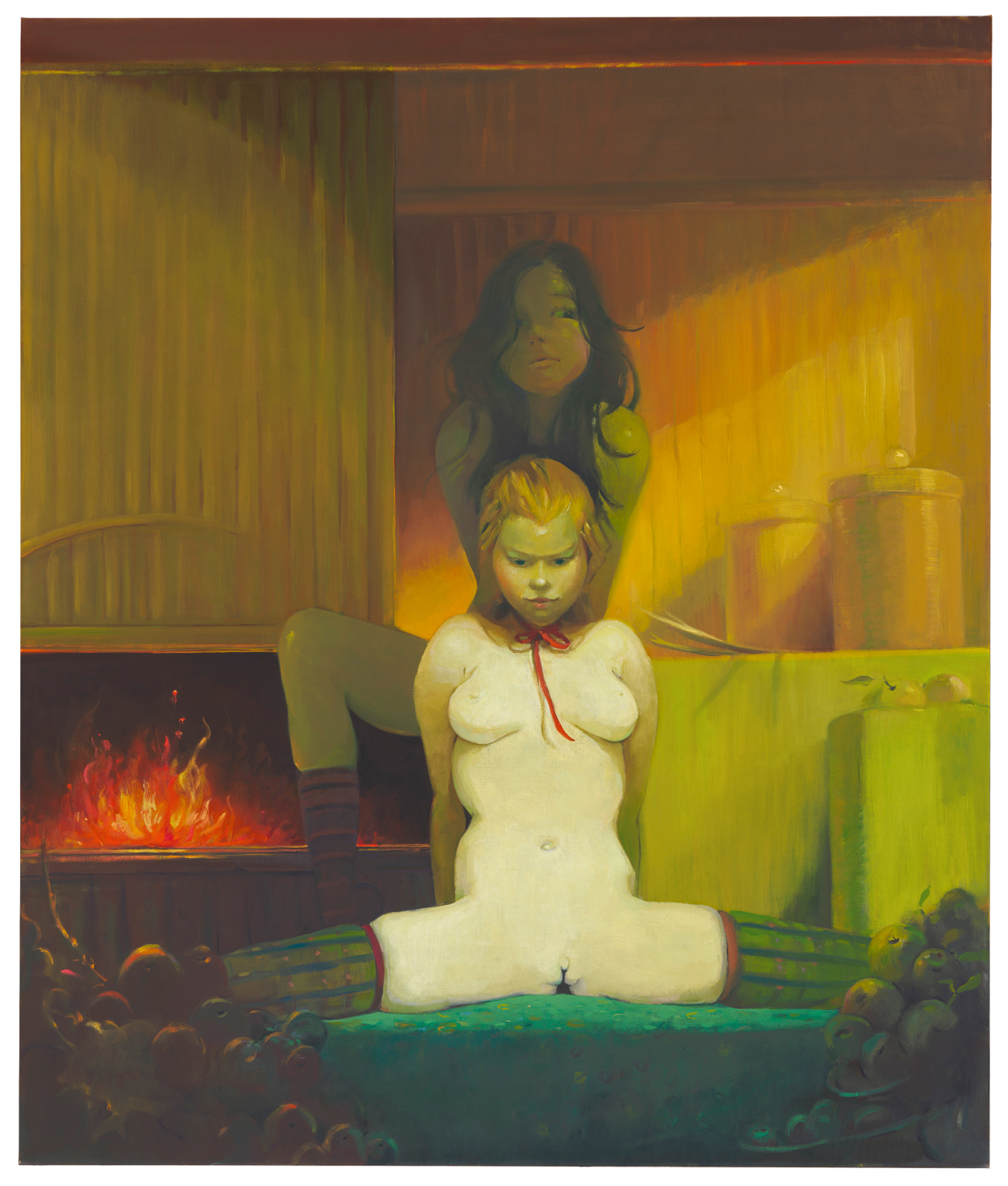

Fireplace, 2010, oil on linen, 77 ¼ x 65 inches

Fireplace, 2010, oil on linen, 77 ¼ x 65 inches

SABINE HELLER — Are you referring to your first show, which was held in 1990, of tasteful, partially covered backs?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Yes. They weren’t me. They were weak. I was painting as an antiseptic schoolgirl, a bottom character. The paintings were saying, “Don’t look at me.” And, in the end, no one did.

SABINE HELLER — They were tiny, and they were of backs, so the forms were literally hiding. It’s interesting how you made the transition from them to your next work. You rejected the uppity values surrounding high art and went from being a bottom character to a top one, by role-playing Frank Booth from David Lynch’s film Blue Velvet.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — It was simply more fun than being me.

SABINE HELLER — Does inhabiting a male character help you to achieve dominance within yourself?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — No. It was about that person’s character rather than his maleness. He was more pathetic than powerful, which is what interested me. He was voyeuristic and ordered the women in the paintings, “Show me your pussy!” while they were trying to hide. To make it believable, I often imagine what it’s like to be in one of my paintings, even as an inanimate object.

SABINE HELLER — So you’re a conductor of sorts, performing in your own art.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I’ve taught painting, and I love how students react to the question, “Are you manipulative?” They’ll say, “No!” And I’ll explain how a great painter is a master manipulator.

SABINE HELLER — People want to know if you’re misogynistic, or if you’re reinterpreting the female nude.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I’m lucky to be able to move forward. I used to think the art police would take my brushes away if I didn’t pick a side. But I can’t — that wouldn’t be true to myself.

SABINE HELLER — You paint nudes within landscapes, placing them in a dialogue that compares the wantonness of nature to the female psyche, and your characters rarely look at the viewer, even if their vaginas do.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — The gaze is deliberately confrontational. I chose when to ramp up the confrontation and when to dial it down.

SABINE HELLER — You come under fire a lot, but you’re remarkable at fielding criticism.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I do take a beating. It used to hurt, but now I recognize that it’s a compliment. What matters is how I react to it. I have to be strong enough to strap myself to a mast and be more grounded than what’s coming at me. Am I supposed to hide? I can’t stop showing, even if it doesn’t feel good to get smacked, humiliated, and told that I suck. You have to realize it has more to do with what’s outside of you than inside, that it’s separate.

SABINE HELLER — Do you like to ruffle feathers?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I like the notion that what’s depicted in a picture should behave the way the picture wants it to behave. I don’t want my pictures to be up to any good. I like the idea that they’re troublemakers. So if I’m told they’re bad for the world, it pleases me. I don’t want to make something that’s an antidote. I want to pose questions. That’s what I do. I suppose I strive to bother people and to be loved for it. That’s the dream.

SABINE HELLER — Tell me something you actually dreamt about in your sleep.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I once dreamt everybody was looking at my baby pictures in The New York Times and saying, “What a cute baby she was.” It reveals how pathetic artists are. You want your audience to love you like your parents did. But guess what? Your parents didn’t always totally love you. You had a stinky diaper. So I make paintings that are meant to disturb. A screaming baby isn’t going to get hugged as often.

SABINE HELLER — True, but the only way art moves forward is by breaking rules and causing disruptions.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I accept that my work is potentially terrible. But I don’t care because it’s not for me to judge. As a creative person, if you think what you’re doing is right, it means you’re following a path. If you’re sure it’s right, it’s because everybody’s patting you on the back.

Fireplace, 2010, oil on linen, 77 ¼ x 65 inches

Fireplace, 2010, oil on linen, 77 ¼ x 65 inches

SABINE HELLER — By definition, uncharted territory can’t be right.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I’m smart enough to know that when the establishment isn’t supportive, you’re doing something right. They don’t want the avant-garde. They have an idea of taste, of what’s right and wrong. I’m not saying I’m the solution. But they’re not open. So I’m grateful for the resistance because it pushes me. As a painter you have to recognize that when you look at something, it’s your limitations and range of experience you bring to the work. Once you see that, you can peel the onion and grasp what’s happening. People come to a picture and get bossy. They want to control their reading of it, rather than enjoy the ride and let it be like a dream. That’s part of my technique. The one thing I need is room for trust and faith in myself — to be open to what comes up and not squash it all the time. It’s amazing how much resistance there is to wanting to be free.

SABINE HELLER — Free to occupy one’s own mental space?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — That’s like Erich Fromm’s idea in Escape from Freedom — that people choose totalitarian systems more than they do others.

SABINE HELLER — Freedom can be terrifying.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I’m not saying I’m a great example of living freely, but I am a small one. Since I’m married and don’t have children, people assume that I don’t like them or can’t have them. The point is having the freedom to be oneself. Should I have kids because I’m capable of producing them and have a live-in sperm donor?

SABINE HELLER — Have you always been so cerebral, even as a child? Were you mischievous?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — When my mom pushed me around in a carriage, I would say hello to strangers. She said her baby was running for mayor. Not surprisingly, I grew up in a large matriarchy, with a lot of women talking. Later on, I was definitely naughty. I got into trouble at school and got bad grades in most subjects, although I read a lot.

SABINE HELLER — Is the naughtiness in your art also in you? Or is there a duality at play?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — There’s a duality at play, and the naughtiness is there. It’s neither-nor. We’ll never really know. I resist reading Van Gogh’s biography because it’s much more interesting to not figure it out. Why does it matter, really?

SABINE HELLER — It only really carries significance to those who assume you’re condoning concepts or ideals by portraying them.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Some people confuse art with autobiography. It’s a shame, and a limiting way to view art. People imagine I’m a libertine. On the contrary, I’m more prudish than I care to admit.

SABINE HELLER — Why do you embrace pornography? Is it just like Playboy and Penthouse, or does it get wilder?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — There are many reasons — some I can guess and some I can rationalize. I saw Playboy when I was a kid. It was hidden, but we found it! And it shocked me. I also like that it seems the wrong thing for me to include, when what I’m looking for is transcendence and beauty. It’s important for me to have a whiff of the demonic. It catches me off guard and makes me laugh.

SABINE HELLER — Do you watch porn?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Sometimes. Years ago, we had a film lying around that featured a bossy redhead and her sweet brunette husband on white satin sheets. I was looking for a fantastic version of my husband and me.

SABINE HELLER — In your work I see traces of the woman-child, or the sexualized child, who becomes the childlike woman, like Persephone or Marilyn Monroe. She becomes aware of her sexuality too young.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Something usually sexualizes you. You may not even remember what it was — it can be a single comment. When I made the series Bad Babies, I was doing a Frankenstein makeover. The body in it was part adult, part child. It was like pulling dolls apart and putting them back together in a different way. I wanted the painting to speak about shame and the inability to hide it.

Imprint, 2006, oil on linen, 48 x 32 inches

Imprint, 2006, oil on linen, 48 x 32 inches

SABINE HELLER — The eyes of the figures are almost haunted.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I had adult characteristics — like pubic hair, for example — pop in to capture the feeling of not wanting to be seen as an adolescent. The figure in The Ones That Don’t Want To: Kelly Marie is trying to dissolve, but can’t. Bad Babies came right after the “back” paintings, and they were about wanting people to understand the paintings themselves. They’re anthropomorphized — like, “Look at me, but don’t look at me.” The “back” paintings were like, “Don’t look at me.” These were the step in between: “I’m going to stare back at you if you stare at me, but at the same time if you stare at me I’m going to disappear. But I’m also going to assert myself and make you feel really uncomfortable.” I’m constantly playing with who’s the top and who’s the bottom in the painting.

SABINE HELLER — You’re often mentioned in the same breath as John Currin, who also has sexual themes in his work.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Well, we met on my first day at school. At the time, he was making abstract work. One of the nice things about John is that he loves interesting art, no matter who creates it. He has encouraged me like no other artist has.

SABINE HELLER — That’s interesting. How did he make the transition to figurative painting?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — One day John showed up at a figure-painting class with a special palate that had an old-fashioned thumbhole in it. He had pointy brushes and a small canvas. It was like he had a toolkit for making paintings. He might as well have worn a beret — I’m surprised he didn’t have a French easel. Anyway, he produced great work, and everybody thought, “Where did that come from?”

SABINE HELLER — Where did it come from?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — His mother was a refined musician. She had him take violin lessons with a Russian woman whose husband was a realist painter. He taught John everything he knew.

SABINE HELLER — Who made waves first? Although I can’t imagine that it really matters now.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — People say John was the first, and he did have a show that made an impact before I did. In some ways, he warmed up the audience for me. He took a lot of heat. It’s good to have allies.

SABINE HELLER — Your work is actually quite different from his.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I’m interested in turn-of-the-century painting, whereas he’s more mimetic. His paintings are very close to being terrible, but there’s something that keeps them from being that. That’s an incredible quality, to be willing to go right up against something really God-awful.

SABINE HELLER — What was Yale like for a working-class girl from Philadelphia?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I was taken seriously as a painter by serious painters, but I was shy and didn’t say much. I was devastated by how brilliant everyone was. I felt embarrassed by my lack of knowledge. I had never been around so many smart people, and I knew I should just listen to them. The one thing I had going for me was that I’d seen a lot of art. I recognized early on that American art had to return to European traditions, that the old school we worked so hard to overthrow was important.

SABINE HELLER — How would you define your relationship to kitsch?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I like kitsch. My favorite definition of kitsch is in The Unbearable Lightness of Being: “Kitsch is the absolute denial of shit.” Kundera defines shit as the inevitability of our own death and decay, and kitsch represents the avoidance of that. To me, most things seem like kitsch.

SABINE HELLER — What about taste?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Good taste is in itself bad taste. What makes it bad taste is that it’s often not original, so there’s something distasteful about it, depending on what you’re after. I recently looked up the word “taste,” and apparently there’s a fifth flavor our palate can detect. Of course, we can taste sweet, sour, etc. — and there are incredible mechanisms in our mouths that relate it all to the brain — but there’s one taste we seldom experience. It’s found in some Asian food, but we’re not accustomed to it. And there may be other tastes we don’t even know about.

SABINE HELLER — So our taste is governed by what we already know.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — It’s what we’re used to. You have to develop a taste for things. Some people don’t like flavors that others do. It’s like art. It’s interesting that we use the word taste to define art, but don’t really examine it in the way we do when it comes to food. It also speaks to snobbery. I can’t eat stinky cheese, but I don’t judge you for loving it. But often people who do love it look down on those who don’t — like, “You’re not there yet.” It’s because you’ve added something, not subtracted something. We call it our palate. In art, people who have broader taste are looked down upon as not being critical.

Faucet, 1995, oil on linen, 72 x 60 inches

Faucet, 1995, oil on linen, 72 x 60 inches

SABINE HELLER — Etymologically, “chintz” and “kitsch” are related.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Funny you should say that. I’ve been interested in the Laura Ashley phenomenon. It seemed to be a high-class person’s idea of low-class taste, which intrigued me. Yet it made its impact by being a low-class person’s idea of high-class taste. I even saw it in my own family — the tradesmen went on to have successful businesses, living in suburban mansions, while we stayed in a little box house. Their wives decorated their homes floor-to-ceiling with Laura Ashley. It was like a rush to be an Anglophile, which is a typically Irish impulse — to beat the English by out-Englishing them. When I was teaching color at Princeton, I came across a Laura Ashley catalogue and decided to use her ideas. Taking red, yellow, and blue, the color triad, I made Blonde, Brunette, Redhead. It was a play between the best and the worst of the same ideas of color.

SABINE HELLER — Women’s breasts in your work are generally large, almost swollen, and often have very erect nipples.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I guess I’m talking about fecundity, like in the painting Outskirts. I asked a friend to pose for it. She was older and had just had a baby, so her breasts were droopy, and the nipples were really pulled down by the milk.

SABINE HELLER — That feeling of fecundity is intense, especially against the backdrop of the voyeuristic tension you create. There’s something truly overwhelming that emanates from your work, and it draws one in.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — That has to be the better part of me. Maybe it’s something I can’t necessarily do as a person, but can do in a painting. I remember seeing a Van Gogh show and thinking, “Wow, this isn’t the work of a madman!” What knocked me out was how clear he was, clear as a bell — he had access to the universe when he was painting.

SABINE HELLER — Why do you think people have a hard time understanding that you’re not a gay painter?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — I’m not gay. I actually tried to be. That kind of matriarchy exists in my imagination. When nude women are touching, most people simplistically define it as being gay. It has a little gayness to it, just like I think we all have a bit of gayness to us.

SABINE HELLER — Are there any photographers that you like?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Diane Arbus, because she didn’t judge her subjects. One of her most famous pictures is of a Mexican dwarf. There was a rumor that she had sex with him before the picture was taken. I don’t know whether she did or not, but he’s sitting with a towel draped across his groin and looking at the camera with this incredible machismo, taking total control. All the potentially marginalized people she photographed are like that. What she’s saying philosophically is that we’re them and they’re us.

SABINE HELLER — Like you, she doesn’t turn her subjects into others. In Triptych, the judging occurs on the canvas. The moralizing force is the peasants — the nel’zia. You informed me that the word is Russian for “don’t.”

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Yes, the peasants are the chorus, the super ego. I created them because I needed a face. I had repurposed the girl from Walking the Dog, and reacted to that by painting the main crotch shot. I thought, “Man, that’s so nihilistic.” I mean, to offer the viewer nothing but your asshole — and it’s nothing but asshole.

SABINE HELLER — Someone said that our deepest fear is not that we’re inadequate, but that we’re powerful beyond measure. The self is the scariest place.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — To realize one’s power would be like being in Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. People would be sticking flowers in each other’s butts and enjoying it. The ass wouldn’t be a place of fear, but of pleasure. We have so much order, whether it’s Santa Claus, the Pope, God, or whoever — all these long-beards — saying “No.” No to being a woman, no to having sex, no to being juicy.

SABINE HELLER — So to all that you say, “Yes.”

LISA YUSKAVAGE — My parents had this bat-out-of-hell notion — the idea of immigrants leaving behind the dirt, cold, and starvation. There was nothing behind us. So I was not considered as being less than the men in my family.

SABINE HELLER — It’s empowering to have that kind of support, and to have nothing to lose.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Being an artist is a walk in the park compared to doing hard labor — or whatever I otherwise would have been stuck doing. When I get a nasty response from a critic, first I’ll think, “That hurt my feelings. I thought he was my friend.” But in a millisecond a voice says, “How cool is that? You throw a punch with a painting, and someone punches you back with an idea.” The fight is on, and I love being part of it. I can’t shrink, or act like a baby, or get mad when I’m actually being seen and people are taking me seriously. That would be crazy, considering the kind of swamp I could have lived in.

SABINE HELLER — How did Bosch’s euphoria influence your painting called Outskirts?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — There’s a detail in the garden in Bosch’s painting in which everyone is eating a shiny red object. I assumed it was drugs, but it could just be joy. People are enjoying their bodies in a childlike way. The ability to be an adult and still play is a form of heaven. That’s why people do drugs, to lose their inhibitions. As you get older, you lose your playfulness. Bosch is showing us how to bring adulthood and playfulness together. He even has that guy sticking flowers in his happy friend’s anus. Bosch clearly painted the guy whose ass is being raped by flower stems as a smiling figure.

SABINE HELLER — Flowers up the ass was pretty progressive in 1490.

LISA YUSKAVAGE — My attraction to that detail told me something, so I started drawing an ass and flowers on the canvas. I always liked the idea of someone riding somebody or humiliating somebody. So I put this woman on top of this butt and went from there. Next I discovered a kid, and then his twin showed up. I Googled “twins back to back,” and so many images came up. One thing led to another. The guy leaning on the stick is some guy I found in The New Yorker — he walked through Afghanistan.

SABINE HELLER — To end our discussion, what do you think are the biggest obstacles you face as a female artist?

LISA YUSKAVAGE — Men were not my biggest obstacles. It’s not just about being a woman. It’s also about my social status and the fact that my family is uneducated and comes from peasantry. I worried about how I would pay my tuition. If you’re working class, you don’t get scholarships — my parents made a little too much for me to get one. It was especially like that in the ’70s. Nowadays we’d have been considered poor. But my parents were too proud to take from the system. The real terror was of not making ends meet — of falling away, of disappearing.

END