Purple Magazine

— S/S 2017 issue 27

Alan Vega

ghost rider New York

interview by JÉRÔME SANS

portraits by ARI MARCOPOULOS

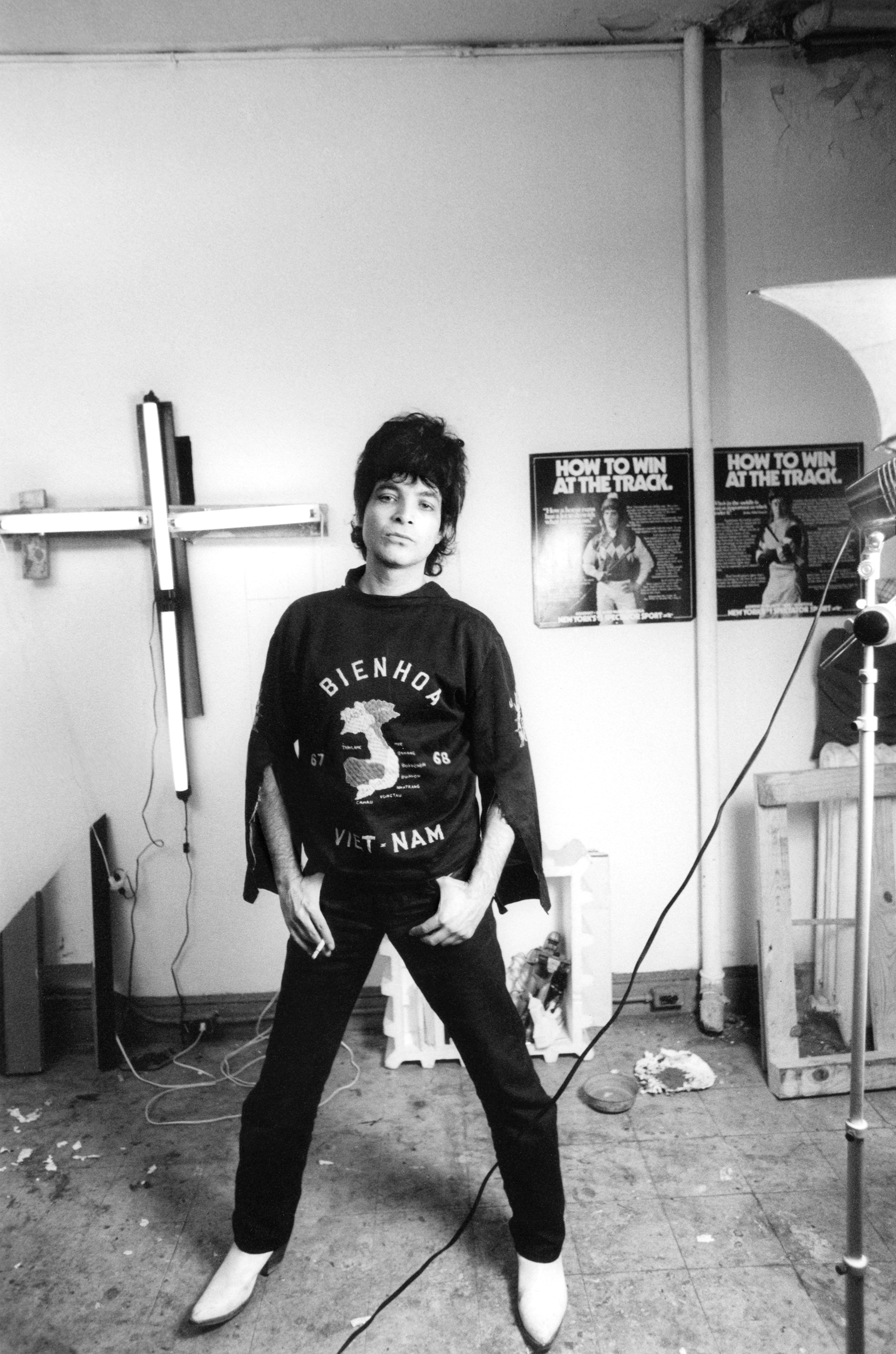

Alan Vega in his loft in Fulton Street, New York, 1981

Alan Vega in his loft in Fulton Street, New York, 1981

An artist, musician, and pioneer of electronic music during the heyday of Cage and Stockhausen, Alan Vega was both the first punk and an alluring rock-a-billy crooner. The cult-like following of his band Suicide — the first to use a drum machine — ultimately defined him as an underground New York icon. Never playing for commerce, he devoted his life to art, music, drawing portraits, and the elaborate wire-infested light sculptures he made from junk and found materials. First represented by the legendary OK Harris Gallery, in the 1980s he showed at the powerful Barbara Gladstone Gallery, and later worked with Jeffrey Deitch. He died in his sleep on July 16, 2016.

JÉRÔME SANS — Before making music in the ’60s, you first started painting. Why?

ALAN VEGA — When I was a young man, I attended art school, at the City University of New York, or CUNY, Brooklyn. In school, you tend to explore all mediums, but mainly I focused on painting at first. I was into abstract art, but I also loved doing portraits of homeless people — called “bums” in those days. After art school, in order to make some money, I started doing painted portraits of people, on commission. But I never stopped drawing the portraits of unknown men — desperate, homeless people. For some reason, I identify with them, being that I am the “king of the bums.”

JÉRÔME SANS — Do your early works still exist?

ALAN VEGA — I’m not sure. Over the years, I have seen a few of the things that I sold. I would imagine that some commissioned painted portraits I did are still in some people’s homes. This was so long ago, and I have moved to so many different places, and I never really kept very much from move to move. But along the way, I gave drawings, paintings, and light sculptures to some of my friends — so those

still exist.

JÉRÔME SANS — Was art school important for you?

ALAN VEGA — I was fortunate to have some truly great teachers in art school. They were great artists in their own right, and because of that, they were truly inspiring. At the same time, this became a difficulty. I was influenced by their work to the point where, when I left art school, it became harder to find my own voice. It took me 10 years to find my own style, my own self. While this was happening, I was also making electronic music — not thinking that I was ever going to have a career in music, but just for fun.

JÉRÔME SANS — Do you remember the names of these teachers?

ALAN VEGA — Many I will never forget. Ad Reinhardt was a huge influence on me, with his black-on-black paintings. Kurt Seligmann, one of the original Surrealists. And some other great artists, like Burgoyne Diller, a pretty damn good painter, and Jimmy Ernst, the son of Max Ernst. As you can see, I was pretty lucky to have had some amazing teachers. At the time, it was overwhelming — so much information. At times, I felt really in over my head, wondering what I was doing in the midst of such greatness.

JÉRÔME SANS — And how did the idea of the light sculptures come about?

ALAN VEGA — For several weeks, I was working on a very large canvas that ultimately worked its way into becoming a one-color painting — purple. One day, I noticed that as I walked across the room, back and forth in front of the painting, the color would change from brownish purple to bluish purple, etc. The problem was, since there was only one light, coming from the ceiling, I had little control over how the color on the painting was perceived. I didn’t like that. I wanted it to be that one color. I wanted to have more control of the color. All of a sudden, a lightbulb went off in my head — I had an epiphany! Why not take the light down from the ceiling and plaster it right onto the painting, to be able to control the color. That’s when I became a light artist — that began a new creative life for me. First I put one light on the painting, then several lights, and then one day I took the painting out of the equation, and it became just light sculptures. Light for the light itself.

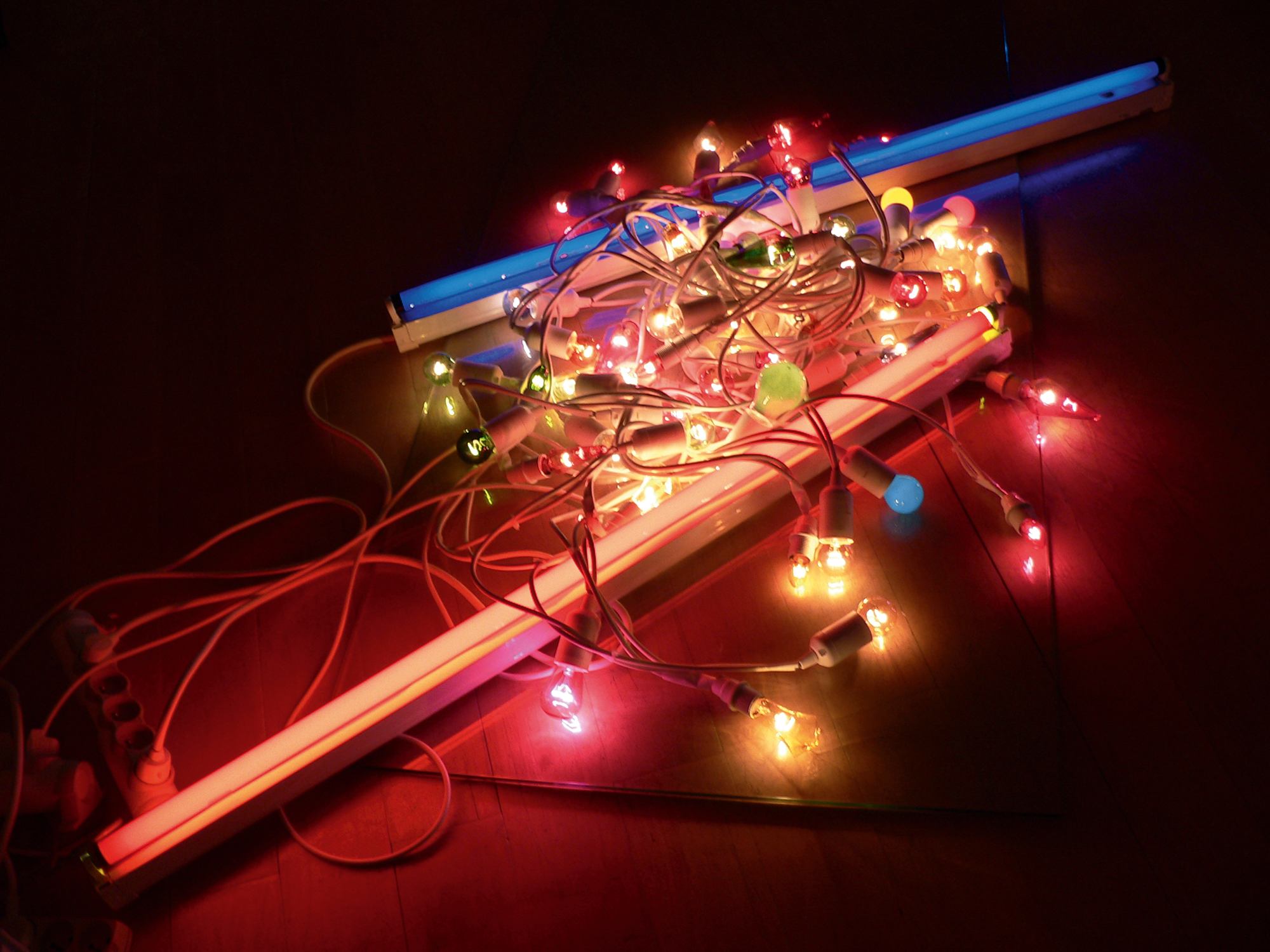

Alan Vega, Infinite Mercy, 2009, installation view at MAC Lyon photo by Céline Bertin, courtesy of Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris

Alan Vega, Infinite Mercy, 2009, installation view at MAC Lyon photo by Céline Bertin, courtesy of Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris

JÉRÔME SANS — Did you exhibit these pieces at that time?

ALAN VEGA — No, I didn’t show the light sculptures right away. It was a few years later, when I was in a group show at the Project of Living Artists. One day, a famous art critic from Canada came to the show. He must have really liked what he saw because he went to see Ivan Karp at OK Harris and mentioned my work to him. Ivan discovered Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist. He had a gallery in SoHo. Mary Boone was also in SoHo then — so there was an art gallery scene forming. Anyway, the next day, Ivan came to the show. He told me he wanted to show my work at his gallery and asked if I could be ready in three weeks. In those days, when an art dealer discovered you, it could take years to actually get a show because they had scheduled shows well in advance for their current artists. Here I was being invited to have a show in three weeks. It was mind-boggling, and I was blown away. I said I’d be ready in three minutes. I had four or five one-man shows with Ivan at the OK Harris Gallery starting in the early ’70s.

JÉRÔME SANS — Tell me about the Project of Living Artists — a gallery open 24 hours, wasn’t it?

ALAN VEGA — About six of us got together and applied for a grant from the New York state government, an art grant. We got the grant and used it to open up this space and called it the “Project of Living Artists.” It was not a traditional gallery, just an open space for anybody to do art, music, or any creative thing, whatever they felt like. We kept it open 24 hours a day, and anyone who wanted to use the space was welcome to it. We took turns watching the place and keeping it clean. Every month, we got a little salary, and I basically lived there for a while. I was homeless in those days.

JÉRÔME SANS — Was the place you created at that time like a Factory, a crazy place where everything could happen?

ALAN VEGA — Yes, it was kind of like the Warhol Factory, in a way. There were some crazy people around. Sometimes it was rather difficult.

JÉRÔME SANS — Were you thinking at that time about making music?

ALAN VEGA — Starting in the late ’60s, I was always making electronic music, with all kinds of stuff, whatever I could get my hands on. And then, with the Project of Living Artists, it gave me a place to create in. And that’s where I met Marty Rev, and together we formed Suicide. One day, Marty just showed up. He had been immersed in the jazz world with his band Reverend B, and I think he was feeling that in some ways jazz was coming to an end for him. And I was feeling I needed to expand my art into another dimension, something with a performance element. So we both kind of needed each other, not always for the same reasons. And that was it. Suicide started, and the rest became history, I guess.

JÉRÔME SANS — Why did you call your band “Suicide”? Was it to kill the other part of you?

ALAN VEGA — We were brainstorming on band names and came up with Ghost Rider, a comic strip character — which was made into a film recently, with Nicolas Cage. In those days, I was into comic books, and he was my favorite character. A title of one particular Ghost Rider story was “Saint Suicide.” We thought about it and said, “Let’s call it ‘Suicide’ because it means a lot of things.” It is not only about death; it is also about life — changing your life. It’s suicide when your life as you know it is about to end and become something else. You know what I mean? Also, these were very bad years with the Vietnam War, and it was a very bad time for the city of New York. Our beloved city was crumbling around us, but I loved it. I used to say that it was the “best of times and the worst of times,” like Dickens said. And yet, we all had a great time. We had this wonderful space where we made art and music. I was showing with Ivan Karp. I did great shows, but I didn’t sell much. So, I felt very rich creatively, but I was dirt poor.

JÉRÔME SANS — Were you one of the first to invent electronic music? How did you come up with this form of music?

ALAN VEGA — Yes, in some ways. We were the first “rock” band to use a drum machine — I know that. Marty and I both knew that the ’60s style of rock n’ roll was already dead. We didn’t use the drum machine yet, but we knew it was time for a new direction. Actually, for the first show, we had a guitar player, Paul (a painter and sculptor, as well). He was not a traditional guitar player; he made noise with the guitar. By the second show, Paul quit, so there were only two of us and no guitar, no drums. We thought about getting a drummer, and then we found a drum machine. And that was it. We had found our sound.

JÉRÔME SANS — What is your point of view about today’s music? Do you like it?

ALAN VEGA — There is always going to be one crazy thing that I will like, and the rest for me is nothing. Most of the sound of the music I hear is not new to me. But then I’ll hear something that really catches my attention. I felt it when rap first got out. But I wouldn’t say that I listen to a lot of other people’s music these days. Mostly because I’m busy making my own music and working with a few different musicians. To me, doing music is my life, more than listening to other music. In general, for me it doesn’t sound as powerful. I like powerful music, you know what I mean?

JÉRÔME SANS — Of course, we love such music. Do you still collaborate with the same partner for your new music?

ALAN VEGA — On my album Station, I collaborated with my wife, Liz Lamere, and my longtime engineer, Perkin Barnes. They are both great musicians, and Liz is a great player, so I’ve chosen to work with them for many years — the last six solo albums. My young son, Dante, who did a vocal track on Station, has been playing keyboards in the studio on the new stuff. So, it is truly a family affair. Lately, I’ve also begun working with a couple of the guys from A.R.E. Weapons — Brain McPeck and Matt McAuley. They are great guys, with true energy and passion for music. We’ve done a few songs and are still going, so we’ll see where it takes us. Over the years, I’ve done many collaborations, with Pan Sonic, Alex Chilton, Ben Vaughn, and Ric Ocasek. I’ve also produced other bands and contributed vocals to many songs by other artists. I often get stuff sent to me, and sometimes I hear something. If I feel a connection, I’m usually pretty open to working with other artists.

JÉRÔME SANS — But have you kept doing art all these years?

ALAN VEGA — Yes. I love making art — it keeps me alive. I always have works in process lying around in various states. When I’m approached to do a show, I focus in and bring it to completion. I like to keep a lot of things going at once — the music, the visual art, and writing. I’m starting to get back into photography. I have ideas about what I’d like to do with photographing light — but haven’t yet figured out the technology. Usually I just go by trial-and-error to figure out how to realize my idea. Sometimes, with so much going on between the music, the art, living life, and raising my son, it’s difficult to keep it all going — but I love it all.

Alan Vega in his loft in Fulton Street, New York, 1981

Alan Vega in his loft in Fulton Street, New York, 1981

JÉRÔME SANS — Could we say that the recurrent thing in your practice is your portraits, which you do in the evening, as you explained to me a few days ago?

ALAN VEGA — Oh yes, the thing that I do most consistently is the portraits. They are therapeutic. I draw them almost nightly. There must be hundreds of them lying around, and more in boxes in storage. I also write daily, just to keep my thoughts warm. I have piles of notebooks, and these random thoughts and doodles end up being where I go to when it comes time to write lyrics. And when I get stuck writing lyrics, when I can’t write, I start drawing faces. I love faces. And that gets me into the writing, that just relaxes me, cools me out. Sometimes, I never get back to the writing because I get so into the drawing of portraits. That’s where it really starts.

JÉRÔME SANS — These drawings are a bit like a diary?

ALAN VEGA — Absolutely, I was just searching for a word. Yes, you are right — it’s like a personal journal or diary. When I look at them, I say, “Okay.” That’s where I see how I was that night. Because they are each different, depending on my state of mind — even though there is a consistent style that has carried on throughout the years that I have been doing this. Yet, when I first started, they looked a bit stiffer, and then looser and looser as I get older. When I was in art school, I studied anatomy; we had to do that. We did figure drawing — studying the human figure. I spent a lot of time on that stuff. So, in some sense I had an academic training where the figures were concerned. Early on, in my student days, I was a more classically trained artist.

JÉRÔME SANS — Could we say that your drawings are electrical? For me, they are not classical.

ALAN VEGA — It’s so hard to get out of that classical training, to find your own style — that takes years. I used to be so classical, like a mathematician who makes everything by equation. It took so long to get free. And the sculptures helped me with that because it’s something I do abstractly. When you look at the wires on my sculptures, they are like little drawings, like pencil lines, ink lines. They might be abstractlooking, but they freed up my drawing. I need these wires in crazy ways. When I’m making a piece, I don’t think about how the wires will affect things. So much of the wire is used in making things stable. So much wire is used to make lines stick to the sculptures. I get into crazy shapes of wires. Afterwards, when I am looking at the finished piece, I realize that the wires created something. And the shadows cast by the piece are a whole other trip. When I did my shows at OK Harris, people would come in, and they’d be talking to me about how educated, complicated, the work was. They’re looking at the wire things, saying, “Wow, look at this.” And then, at a certain point, I looked at my drawings and said, “If I trace those lines, my drawings could be the wires.” That’s how the sculptures actually help me free up my drawings. When I was young, the drawings were in another place. Now, yes, they have become more electrical — impulses creating the movement of the lines. At some point, when you reach a certain age, you say, “Fuck, I don’t care.” Although, I still never thought of showing these drawings. I did a poetry book with Henry Rollins, Cripple Nation, and that was the first time I published some of the drawings. I hadn’t thought of showing them when I was with Barbara Gladstone, a dealer who showed my work in the ’80s, after Ivan. And I haven’t shown them to Jeffrey Deitch, who represents me now. Just having a look at them is great. I haven’t shown them to anybody else, but my wife sees them, and my kid sees them. That’s about it. I don’t have that pressure of somebody who has to show in a museum or a gallery.

Alan Vega, exhibition view “It’s Not Only Rock’n’Roll Baby!” Palais des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles, 2008, copyright Philippe De Gobert

Alan Vega, exhibition view “It’s Not Only Rock’n’Roll Baby!” Palais des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles, 2008, copyright Philippe De Gobert

JÉRÔME SANS — Have you ever thought of doing specific settings for your shows, to mix art and music?

ALAN VEGA — I feel that my sculptures have never gotten a full treatment in a show. I always felt that each piece should have its own space and light. Maybe in a room with partitions, to control the light created by each piece. With my music, each song is separate. No matter how connected to the album as a whole, it also gets individual treatment. I’d like to get that more with my sculptures. The whole thing is about light. When you are alone with the piece, you can see all the shadows that come over its surroundings. When I work on a piece, I work alone in the dark room, creating the shadows and their directions. In most gallery or museum situations, there are other pieces around. The light of other pieces affects each piece. Because the room they hang in is different, the environmental quality of a lot of the pieces is lost. They lose the quality of the light, the spirituality I feel for the light. My dream is to give each piece a separate room because environmentally it will create a certain aura. Up until now, the pieces haven’t had that unless somebody bought it for their own, to free themselves.

JÉRÔME SANS — Yes, I agree. That would be a dream come true. Have you ever thought of linking up your musical performances on stage with your visual art?

ALAN VEGA — When performing music, I have always wanted to have visual pieces there. But when you are traveling, it’s a lot to carry these things around. The works are fragile and heavy. If I had a big show, I would play with really big pieces. I would love to do that, of course, but to be honest, it becomes a pain in the ass when it just requires too much to execute. It numbs the creativity for me. That’s why, when I’m doing concerts, I never go to the sound check anymore. I want to hit the stage and just go for it. It’s 30-plus years that I’ve been doing this, so loading it in is a pain in the butt. Still, over the years I’ve done some combinations of the sculptures with the music and performance. The last one was in Haarlem, Holland a few years ago, maybe 2004. I made a light sculpture that hung from the rafters in a church. It looked like the crucifixion of Christ. Hundreds of small strobe lights, set at different speeds, hanging from the ceiling and pooled on the floor. And dueling smoke machines blew smoke through the light. The performance was at sundown, and the ceiling was all skylights. So, after I put the lights together in the morning, the crew spent the afternoon covering the ceiling with tarps and tape, and draping black curtains around the piece — so it was tent-like for the performance. There were several places where the covering fell a bit to let light sneak through and beam across the space — which was cool, and dissipated as the sky darkened. Liz, Dante, and I came out and did some crazy performance of some music we were working on at the time. We played basically through a boom box, with minimal vocal amplification. People came in and surrounded us in a circle. The sculpture became a campfire on Pluto.

JÉRÔME SANS — Do you have a new album or music collaboration on the way?

ALAN VEGA — I’m always working on my new album. My last album, Station, has been out since last spring, and as I was finishing it, musically I broke into another new place. So I didn’t wind down after Station. I’m probably pretty close to having another solo album done, but who knows how long it takes. I hope not five years like the last one. If I have five years left anymore, for Christ’s sake.

This interview was conducted in 2008 and was published in the catalogue of the exhibition “It’s Not Only Rock ‘n’ Roll, Baby!” at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, curated by JÉRÔME SANS. ALAN VEGA is represented in Paris by Galerie Laurent Godin.