Purple Magazine

— Purple 25YRS Anniv. issue #28 F/W 2017

Betty Woodman New York / Florence

interview by SELVA BARNI

photography by GIASCO BERTOLI

The art of pottery and ceramics has been largely considered a minor decorative art form, even though Picasso raised its status while living in Vallauris in the 1950s. American feminist artist Betty Woodman, age 87, has devoted much of her life to it — creating art objects that are both vases and sculptures, and colorful ceramic wall pieces. Her vibrant Matisse-inspired ceramic works, made between New York and her house near Florence, starkly contrast with the darkness of her late daughter Francesca’s photographs.

Betty Woodman in her studio, Boulder, Colorado, 1961, photo George Woodman, courtesy of the artist

Betty Woodman in her studio, Boulder, Colorado, 1961, photo George Woodman, courtesy of the artist

SELVA BARNI — Here we are on the hills of Florence. You just came back from New York via Vienna, where you had a show. Since the 1960s, you have divided your time between Italy and the US. Why such radically different places?

BETTY WOODMAN — I’m a hybrid. I don’t feel totally at home in America or here. I turn off New York to be in Italy, and turn off Italy to become who I am in New York. There’s always a discomfort in this movement, and I think that the work is also not very comfortable in switching from one studio to the other. But this has been very important to me. I constantly have to rethink and do things in a different way, which has somehow kept my work alive and challenging for me.

SELVA BARNI — What made you want to come and stay here?

BETTY WOODMAN — Well, you know, it is a little like falling in love. What makes you fall in love? I don’t think you ever really understand. I first came in 1951, after art school. I didn’t know what to do. I had a poet friend who was here on a Fulbright scholarship who wrote me to come. So I came. It was amazing walking in Florence and seeing buildings like the Dome or the Baptistery. I come from Boston, where buildings are sort of gray — and I think Boston has good architecture — and I had just never seen anything like this. I was already very involved with clay and ceramics, so I went and saw everything in the Etruscan museums. I had been taught to appreciate an aesthetic of ceramic that was Oriental, rather modest and exquisite in form, and where the atmosphere of the kiln was what made things happen. But here I saw some kind of alchemy that was not related to the use of the kiln. It was about the use of color and the painting of forms. Here, too, I suddenly became aware of the landscape and of the cypress trees, and of learning a foreign language by going to the market… I fell in love with it. The landscape in Colorado, where I lived for 40 years, was beautiful where humans had not touched it. And the landscape in Tuscany is beautiful because humans have touched it. I also met people like you.

SELVA BARNI — Had you already met your husband?

BETTY WOODMAN — I had met him in Boston when I taught a ceramics class. He was my student, a freshman from Harvard who thought it would be interesting to learn ceramics. My mother was also my student. She was convinced she would know me better by learning ceramics and understood why I was so passionate about it. But I dropped everything to move to Italy. George was kind of my boyfriend, but love was not very smooth. I worked in Fiesole in a pottery studio owned by painter Giorgio Ferrero and sculptor Lionello Fallacara. It was amazing. They didn’t know how to make ceramics at all. But it was after the war, and everything was possible. They thought there was a market for ceramics. I just went and knocked at their door and said, “Can I work here?” and they said, “Sure.” I had just finished school and knew everything, the way you do when you finish school. But they weren’t following the rules! That was a very important lesson: rules are there to be broken.

SELVA BARNI — Why pottery?

BETTY WOODMAN — My art teacher at high school taught a pottery class, and I really liked the clay, the handling of it, making something out of it. It was magic. We put the glaze on it and put it in the kiln and then came back and saw that the dull, rusty colors had turned into beautiful greens with black lines. I was also very interested in the idea of making objects for daily use, which I idealistically felt would change people’s lives. I was interested in what the Bauhaus was about. I wanted to be a potter, a craftsperson. I had no ambition to be an artist. George was an artist, a painter, and we did not compete in any way. Later, it became much more complicated for the two of us.

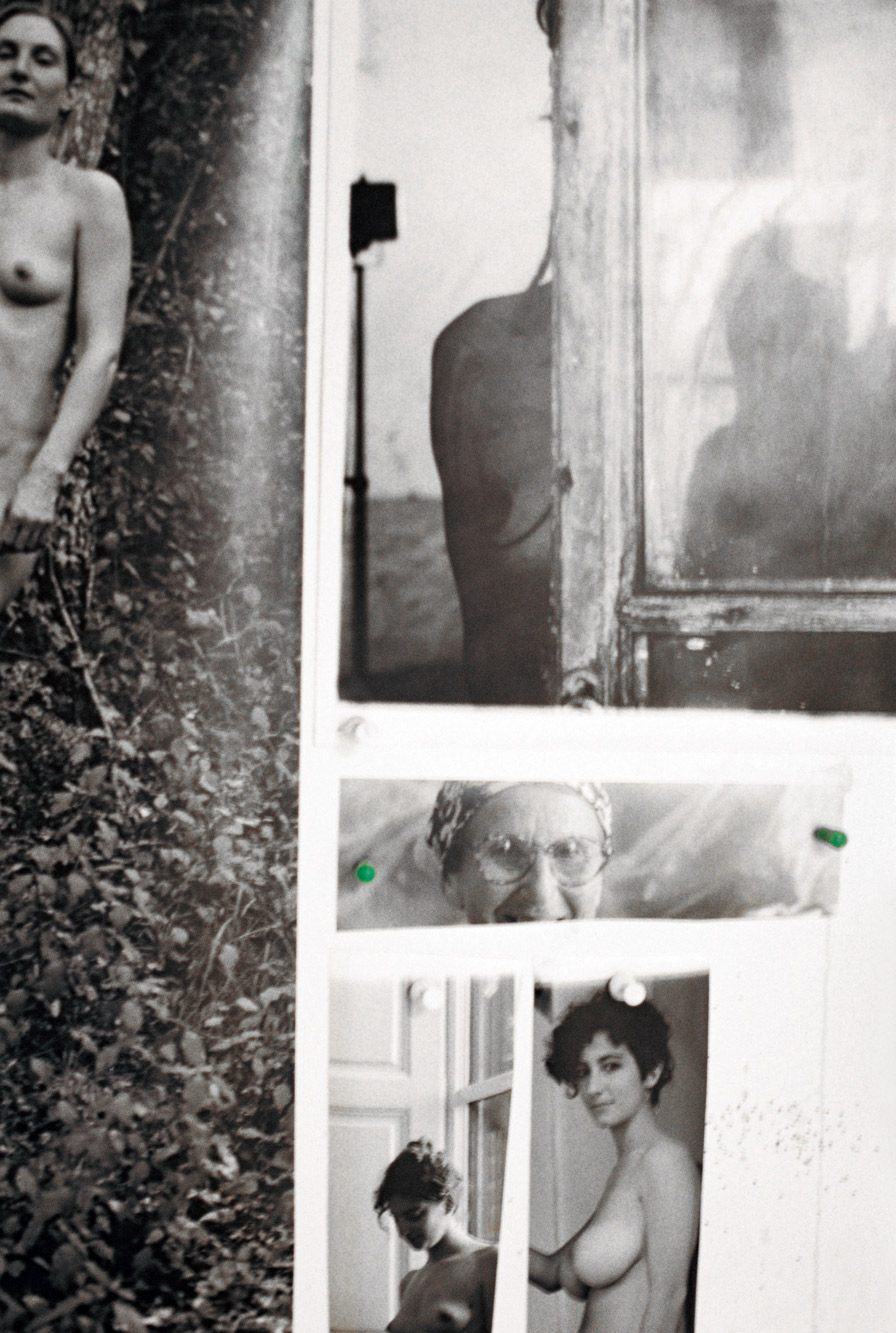

Pictures in her husband George’s studio

Pictures in her husband George’s studio

Detail of Courtyard: Dusk, 2016, in Betty’s studio

Detail of Courtyard: Dusk, 2016, in Betty’s studio

SELVA BARNI — When did your shift from craftsperson to artist happen?

BETTY WOODMAN — It was a gradual evolution. Instead of seeing my work as simply functional, I started to see it conceptually, as an image of function. This has become more clear quite recently, with my shows at Museo Marino Marini here in Florence and at the ICA [Institute of Contemporary Arts in London], and before with the show I did at David Kordansky Gallery in LA. I titled the museum shows “Theatre of the Domestic.” The domestic object is something I have always been in love with, but while the older works were actual teapots, boilers, or casseroles, my new works are paintings that incorporate teapots or casseroles as illusions of a subject matter, so that you can still perceive the domestic.

SELVA BARNI — In one of your recent catalogues, there is a dedication to your mother in which you thank her for teaching you that “domesticity can be combined with ambition and other interests in a woman’s life.”

BETTY WOODMAN — I am happy with that dedication! I had interesting parents. My mother always worked, as we didn’t have enough money. They got married during the Depression, and my father had to stop university and get a job in a grocery store. They were very free-thinking, anti-religious Jews. I was brought up with a great deal of prejudice against religion. Interestingly enough, coming to Italy and seeing all the art that would not be here if it was not for the Church made me think that you cannot just wipe religion out.

SELVA BARNI — Did you consciously transmit the same values to your children? Do you think your approach to life influenced them, as they both became artists?

BETTY WOODMAN — I don’t know. I think, with Francesca, she just was an artist, that’s all; she couldn’t get away from it. As for Charlie, although he was initially doing something else, film and politics, one day he came back from university and said he was going to major in art because that was the only thing he knew anything about. So he started working with video, becoming a sort of pioneer of that medium.

SELVA BARNI — Have you always been aware of the fact that the domesticity of your work would be considered as a feminist act?

BETTY WOODMAN — It’s complicated. By the time the wave of feminism rose in the ’60s and ’70s, those working with clay were excluded from the art world. You were just not considered an artist, and you were not invited to shows. Then something changed: we met critic and activist Lucy Lippard in Colorado, and we had our consciousness raised while discussing with a group of academics and artists. I was older and already a rather successful potter, and I started to be invited to shows. Looking back, artists have always been accepting and instigating social change before other people. The world of ceramics in the US was totally dominated by men, but as their consciousness was raised, they realized there were no women. The first to be invited was me. They responded to what I was doing. Hopefully it was not just a political choice. This question made me feel uncomfortable. I said to a friend, “I don’t need this,” and she replied, “But they need you.” That’s why in the mid-’70s I joined the Front Range: Women in the Visual Arts, a name that referred to both the front of the mountains in Colorado and to the burner of the stove. I was probably involved in thinking about feminist issues because of my mother, who taught me to never back off. Also, in my relationship with George, I was never expected to back off because I was a woman or somebody’s wife. I was not a militant feminist, but the issues raised by my work were. For me, it was not just about making the work — it was about using it; it was as much about putting the food on the table in those dishes as it was about making the dishes. In order to be successful, I didn’t have to adapt to male goals.

Pictures in her husband George’s studio

Pictures in her husband George’s studio

SELVA BARNI — Were the first shows mainly in museums dedicated to handcraft?

BETTY WOODMAN — Yes, in university museums or in the decorative arts sections of museums. I did many, and became well known, and museums started to acquire my work.

SELVA BARNI — In the 20 years since I have known you, your objects have turned into sculptures and compositions that increasingly occupy the space, playing with illusions, while the use of the word “theater” in your titles also suggests the idea of a mise-en-scène.

BETTY WOODMAN — I think this was also influenced by my life in Italy, which is more theatrical than in America. Crime writer Andrea Camilleri often uses the expression “fare teatro,” “make theater,” which means making a drama on purpose to take the attention away from something and shift it to something else. Italy in a sense turns up this. After all these years, this is who I became. It is just part of me. Living here has also given me a keen sense of how American I am, too.

SELVA BARNI — You have probably taken the best of the two cultures.

BETTY WOODMAN — Or the worst.

SELVA BARNI — I opt for the best. How did you end up in Florence?

BETTY WOODMAN — I came with George for the first time in 1960. Five years later, we came back and stayed for one year. I had a Fulbright, and he had a fellowship. We found this farmhouse for almost nothing. George had a grant from the government, and with that money, we just bought it, in 1968. We wanted to be in Florence because it was intensely urban. Colorado wasn’t at all. But I needed a kiln, so it could not be in the city center. The house was 30 minutes away. It was amazingly ugly, completely different from now. People stared at us like we were from outer space. But it had light and water, so we could move in right away, and little by little, when we had the money, we changed it.

SELVA BARNI — At the beginning, you made pottery, and George painted it.

BETTY WOODMAN — That was a period we went through because I didn’t know how to paint my things. But then he grew resentful of how much time it would take him, and I grew resentful because he didn’t want to do it. We had a big fight, and I told him I never wanted him to paint another of my things again. I regret what I said, but I couldn’t go back and found myself making bad copies of his. So I started to do ceramics that didn’t need to be painted. Then we came to Italy with the kids for a year in 1976, during the oil crisis, and I had no fuel to do stoneware, so I started to work at low temperature, a new technique, with no history of the work made with George, and I started to paint.

SELVA BARNI — And color became very important…

BETTY WOODMAN — Yes, it’s something I hope I do well. In the past few years, my main interest has been painting. The ceramics are a very important part of it, and I think they give me the permission to make the paintings. In a sense, what I’m doing fits into the discourse of painting today, which is often not done with paint. In many ways, too, rather than me leading my work someplace, my work has led me.

Pictures in George’s studio

Pictures in George’s studio

SELVA BARNI — In a very spontaneous way, you challenged the idea that a potter can’t be an artist, and a mother can’t be serious about work.

BETTY WOODMAN — Right, or be trapped in your own intellectual ideas and feel you cannot get out of them. It’s fine to say something, but once you have said it, it is important to be able to throw it away. George and I never thought too much, notwithstanding the fact that he was such an intellectual. We just did things.

SELVA BARNI — Thinking is overrated.

BETTY WOODMAN — I come from a family that never had money to pay bills. My mother worked, my father worked, and every time they had a little money, they spent it. Their attitude was shaped by a Jewish society involved with socialism and fresh ideas. They were very open, even about my relationship with George, and I think I learned this from them. George’s family had more wealth, not a lot, but enough for him to go to Harvard and have a car and an allowance. Maybe this combination of very different social backgrounds, which often doesn’t work, made it richer for us. I was always learning from him and he from me. Our behavior was very different, and that made us attractive to each other. Also, he was so beautiful! Which helps.

SELVA BARNI — Why did you want to go and live in New York?

BETTY WOODMAN — The reason was George and his career as a painter. In the late ’70s, there was a movement called Pattern and Decoration, and its main critic was Amy Goldin. George had been making pattern paintings for many years, way before the movement was created, so when she discovered his work, Goldin was very excited and suggested we come to New York. Colorado was like Italy: a very good place to make art, but not a very good place to be an artist. So we moved. We were 50 years old at the time, and we thought rather than be comfortable in Colorado we should try to be artists living in New York. This is when we were not timid, again. Charlie and Francesca had finished school and moved out, so we sold his studio in Colorado to buy a place in New York. Francesca, who was living there at the time, went and looked at real estate and came up with this loft, which we ended up buying. It was easier for me, somehow, because I joined Max Protetch Gallery. It was an art, not clay, gallery, and Max thought he would like to be the first to deal with pottery. I might have been called for the wrong reasons, but I stayed there for 25 years, and that was the right way to present my work: in the context of other art. Max’s gallery was on 57th Street, then moved to Broadway in SoHo and then to Chelsea. He [Protetch] was very successful at selling my work. He also liked that the decorative arts collectors came to his gallery. New York also meant that we started to have conversations with other artists. I started to have a dialogue with other women artists. For the first time, I knew women who were serious, dedicated artists. I did a collaborative piece with Joyce Kozloff!

SELVA BARNI — In that period you also started to occupy the walls.

BETTY WOODMAN — I did a wonderful installation with Cynthia Carlson around 1979 at the Fashion Institute of Technology gallery. She was extruding paint on the wall, and I extruded clay, turning it into a kind of tapestry. And we decided we would copy each other and not make it clear which was Cynthia’s and which was mine. By the time we finished, we weren’t speaking anymore. It took 10 years before we became friends again.

SELVA BARNI — What other artists were you hanging out with at the time?

BETTY WOODMAN — Joyce, Cynthia, Michelle Stuart, Kiki Smith — we are still very close — Richard Tuttle, John Newman, Bob Kushner, and many more. At the time it was SoHo, and then it became Chelsea, where we were living already.

SELVA BARNI — When did pottery start becoming accepted in the art world?

BETTY WOODMAN — The art world always needs something new, a bit like the fashion world. Photography began to be recognized as an art form. Somehow, ceramics was the next thing, and something new to sell to collectors.

SELVA BARNI — A lot of artists had made clay before — Gauguin, Picasso, Fontana… But they were legitimized by other media.

BETTY WOODMAN — Yes, artists have always understood that clay is a fascinating material. It was the critics and historians who didn’t.

SELVA BARNI — Did you ever feel you wanted to “betray” clay?

BETTY WOODMAN — No. I think a lot of artists did, and they moved away from it. They found other materials or realized that the art world was never going to look at clay, so they switched. For me, it offers so many possibilities: different kinds of clay, different temperatures, different atmospheres in the kiln. That somehow has satisfied all my desires to experiment. There is always something else to try, so I never gave up. And suddenly, in the past four or five years, every gallery is showing clay. It came into fashion; maybe it is already out of fashion! What happened, though, is that it often came with a disclaimer, such as, “I don’t know anything about this material… Look, I am doing it.” It is a difficult material to learn how to master.

SELVA BARNI — Pottery has always been marginal. But now there are more crossovers as the boundaries between fine arts and crafts dissolve.

BETTY WOODMAN — Now it is fiber, fiber art. Every month there is a new show about tapestry, about carpets.

SELVA BARNI — So how did you merge painting and ceramics?

BETTY WOODMAN — I became interested in painting and the space that painting takes up. Then I started painting on canvas and having the ceramics become part of that. But it was usually a backdrop, a colored surface. Then I became interested in the kind of perspective I could play with by looking at Indian and Japanese paintings.

SELVA BARNI — The references to Indian, Japanese, and Korean visual cultures add a special layer to your references to Renaissance perspective.

BETTY WOODMAN — Right. I have been interested in all kinds of other art. One of my recent series is called Courtyards and is inspired by a Beato Angelico painting from the San Marco Museum in Florence. It’s a small painting where there is a building, and you are looking through that building into another space. Last summer I did seven or eight new paintings, which all have something at the front and then a space within them and maybe a vase sitting in front, as a kind of metaphorical figure. Within that “courtyard” there are ceramic figures, again vases, which I see as a sort of population living in that space.

SELVA BARNI — How do you choose the titles of your works?

BETTY WOODMAN — It depends. Sometimes it’s places like Arezzo, Sansepolcro, or Orvieto. Sometimes it’s roses or other plants. Sometimes it’s just Wallpaper Number 1, 2, 3, etc. Most recently, I’ve taken my titles from poetry. George really loved Rilke — I was reading him one of his poems when he died — so I have been taking titles from Rilke. The most recent one, for my next piece, is Be All the More Consoled by What You See.

SELVA BARNI — Your later works have used the canvas and expanded even more, creating windows and views. It’s like you’re reproducing the place where we are now: a table looking at two arches that frame a view of the Tuscan landscape.

BETTY WOODMAN — It absolutely is! It also comes from looking a lot at Bonnard.

SELVA BARNI — With the foreground tables and objects as protagonists?

BETTY WOODMAN — The domestic objects, like the bowls of fruit or a bottle, take center stage, and then you see that there is a woman, but you see her later. I make a lot of work that seems arbitrary, but as I make them they come together. I’ve been making sketches. When I paint, I try out the colors on a big piece of paper. I used to throw these tests away, but I finally looked at them and found them beautiful, so I started drawings on them, with brushed India ink. I showed a bunch of them in the show in London and at Salon 94 in New York.

SELVA BARNI — What about these pieces you call Wallpaper?

BETTY WOODMAN — They came about through another series, Carpets. In my studio in New York, I had boxes of pieces of clay. I asked my assistant to place the pieces of white clay on brown paper and draw around them and take a picture, so we would have a record of what’s in each box. While we were doing it, I thought it looked like a rug; I found it very beautiful. So I started to make more of them, then everybody who came into my studio said, “But you can’t walk on them!” and I said, “No, of course you can’t walk on them! It’s not a real rug, it’s an image of a rug!” Then I was showing these carpet pieces in an exhibition and decided I wanted to give something away, so I saved one wall and glazed a bunch of these pieces and laid them out on the wall, and told everybody who came to the show, “You can take one.” In 20 minutes they were all gone. I found these new wall pieces made of fragments beautiful, so I started making some. I made one for Jeanne [Greenberg Rohatyn, owner of Salon 94], but they are not easy to sell.

SELVA BARNI — I’m fascinated by the way the vases expand onto the wall, and how the handles are placed in front of them. Is it a playful approach to illusion?

BETTY WOODMAN — It evolved from observing my process. With clay, you make parts, you make a vase. If you want handles, you make them and stick them to the vase. So instead of putting handles on the vase, I put them on the wall. Then I had to make a shelf, so I made one in ceramic. This came from a visit to my friend Nino Caruso, a wonderful ceramic sculptor. In his house, he had a traditional piece of a shelf made out of clay and something sitting on it, so I thought, “That’s what I’ll do.” Living with a painter and having been very fortunate to travel the world looking at art in museums, I started thinking about the space, and became interested in the way a painting can create a fictional space. Like in Matisse’s paintings of the French Riviera. It is fascinating to see how far away I can take something very realistic, but still have the suggestion of it. The vase has always been a metaphor for a woman, a container. And it is also something easily recognizable and familiar.

SELVA BARNI — Your show at The Met in New York in 2006 had vases at the entrance with beautiful flowers arranged in them.

BETTY WOODMAN — That was an actual political statement on my part: using something does not make it not art. You can use art. This is a statement that the art world finds very difficult to swallow. Because if you use it, it’s not art; it puts it someplace else — curators and people in the art world learned that when they went to school.

SELVA BARNI — Well, everybody tries to define things. But I think it’s very hard defining art today. And also, the very definition of what is “functional” and what is “useful” is extremely ambiguous, as especially in our world they refer to things that are of no practical use, but rather of conceptual use. Needs are taken for granted, and we fully concentrate on desire.

BETTY WOODMAN — What’s interesting here is that I feel I am old and conservative. My art is made to be looked at, not just to be talked about as a concept, and when I say “to be looked at” I am pretty much a formalist, because that’s the way I was brought up. Today, it’s more about issues than about what you are seeing. Do you find that true?

Betty in her studio with Courtyard: Pontormo, 2016

Betty in her studio with Courtyard: Pontormo, 2016

SELVA BARNI — We were brought up and live with the idea that questions are more important than answers and that the work of artists is important when it poses questions in the most persuasive, pensive, and sophisticated way. How would you like your work to be seen?

BETTY WOODMAN — Yes, no… I contradict myself all the time. If you cannot contradict yourself, who can? I am interested in showing formal issues of painting, while some of the people I work with are not interested in them at all. Gallerists don’t always see my work the way I want it to be seen. I think young people have a different aesthetic from mine, and I suddenly look old.

SELVA BARNI — But your work is generating a lot of interest from younger people, and galleries are extremely excited about it.

BETTY WOODMAN — That’s true, and I am very appreciative; it’s nice.

SELVA BARNI — Do you think there is a reason why that’s true now more than a few years ago?

BETTY WOODMAN — I don’t know! I wish it had happened before! [Laughs] You know, George’s death has made me very aware of age. I never thought of myself as being old. I think he felt old more than I did. His death made me very aware of how, you know, I am not just going on forever, while I thought I was just marching along… I certainly had friends die. Francesca died. But this time it has been like, “Wait a minute, this is not going on forever, and it can just end like that.” That is sort of what happened with George; he just died. And he was younger than me.

SELVA BARNI — Does this make you feel the urge to produce and accomplish more?

BETTY WOODMAN — Yes, it does. I said to Dave [Kordansky], “I want to have another show,” and he replied, “Oh well, in a few years,” and I said, “Hey, you know, I am 87.” Anyway…

SELVA BARNI — I’ve always thought you give daily life the dignity it deserves.

BETTY WOODMAN — I guess it’s true! It’s very curious to have three people observe this in my surroundings within two days. I just received an email from Saskia and Matthew Spender, who are staying in my apartment in New York, saying exactly this: “Nothing in the house is unnecessary.”

END