Purple Magazine

— The Paris Issue #31 S/S 2019

gaspar noé

gaspar noé

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

portrait by PIERRE-ANGE CARLOTTI

anatomy of a movie

(“climax” a musical horror film)

RELEASED IN THE US MARCH 2019

OLIVIER ZAHM — How many films have you made in total?

GASPAR NOÉ — Five. I’ve also made one 40-minute film, Carne. Climax is my fifth feature.

production

OLIVIER ZAHM — I understand the film was wrapped quickly.

GASPAR NOÉ — I spent about two weeks filming, a month preparing, and two-and-a-half months on postproduction. We filmed in strict chronological order on a single set, an abandoned school in Vitry, in the Paris suburbs. We invented the story day by day. Well, I scammed the producers a bit, saying that filming would last two weeks. It actually took three weeks. All in all, I spent four-and-a-half months on everything, from casting to postproduction. The production director and I went into fits of laughter when we saw the showing at Cannes. “How on earth did we get it done so fast?” we asked ourselves. “It’s not possible!” Later, I spent a lot of time promoting the film because it’s being released in a lot of countries.

script

OLIVIER ZAHM — You didn’t have a script?

GASPAR NOÉ — I just had a two- or three-page outline. My only real hit so far has been Irréversible, which was done like that, without a script. I didn’t know if it was going to be closer to a documentary or to fiction. In the end, I turned out a sort of a rigged documentary-style piece of fiction. When I was a film student, I was told that Jean-Luc Godard would get a film financed with just two pages, by dropping actor names like Alain Delon or Gérard Depardieu. That was my dream.

budget

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you get backing for a project that was so ill-defined at the start?

GASPAR NOÉ — I went to see producers and told them: “Look, I don’t have a script. It’s a documentary on young dancers. It’s cheap!” They said they were going to try to find a bit of money. Canal Plus didn’t follow up. Arte, against all expectations, put up a little money. The rest came from private investments: Rectangle, Édouard Weil’s company, and Wild Bunch.

OLIVIER ZAHM — A small budget, then.

GASPAR NOÉ — Two million — not enough for a TV movie, even.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you showed it at Cannes?

GASPAR NOÉ — I’ve always showed my films at Cannes, even Carne. It was out of the question that I wouldn’t finish it in time for the festival, whatever category it was included in, even if it was projected on the margins of the festival.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What kind of reception did you get at Cannes?

GASPAR NOÉ — When I did I Stand Alone, I got 50% for and 50% against. When I did Irréversible, things got worse. I got 60% against. With Enter the Void, I got 75% against. With the last one, I got 80% against. So, this time I went in prepared. I said to myself, “This time, if I don’t get 90% of the press against me, then I’m doing something wrong!”

OLIVIER ZAHM — What kind of promotion did you do?

GASPAR NOÉ — When we showed it, no one knew anything about the film. There wasn’t even a plot summary in the Directors’ Fortnight catalogue at Cannes. There was just a picture of a bowl of sangria. Nothing else. So, we made up some fake news, saying that I’d filmed for nine years in 16 countries, just to cover our tracks. It’s a lot of fun to show a film without the public having the slightest idea what it’s about. Or a totally false idea. Strangely, the articles that came out after the showing at Cannes were massively favorable, especially in the foreign press.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You put out fake news about the film?

GASPAR NOÉ — Presidents do it! Why not us? You put out a bit of fake news on Twitter, and the rest of the press picks it up. That’s how we bamboozled the press. I even changed the film’s title, calling it Psyché to cover our tracks because someone posted a summary online, and suddenly stuff started popping up online.

casting

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was this the first time you’d been so successful with the press?

GASPAR NOÉ — It’s the best percentage of favorable articles I’ve ever gotten! I wonder if it’s because the protagonists of my previous films have all been antiheros: tortured, tormented people who do everything backward. It’s always been stories of people who’ve messed up their lives, people you wouldn’t necessarily want to get attached to. Whereas here, it’s kids who are almost heroic or fascinating because of their feats of physical prowess. The film starts with a choreography sequence where you see children dance extraordinarily well — in a way you’ll never be able to dance in your life. Some of them are a bit sexually obsessed, but you can still grow attached to them.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Besides, they’re cool, sympathetic, and beautiful.

GASPAR NOÉ — They’re young. There are 23 characters, including the little boy. They were cast essentially for their physical excellence as dancers. I took the best dancers, but I also took the most sympathetic among them. There were dancers who were very good but antsy during the test shots. I wanted them to dance and play as if they were at a party that was going to last two weeks.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So, the casting call was: “Seeking dancers for documentary.”

GASPAR NOÉ — I discovered voguing, which I hardly knew existed until last December. It was Léa Lamos, one of the dancers I ran into at the filming for an ad she was doing, who told me she was into voguing. I watched and went to a vogue party out in the suburbs. It was so wild, so funny, and electric. There weren’t all the Parisian yuppies. There were real dancers. There were very few infiltrators from the Marais. Because when they vogue in the Marais, you get the sense that it isn’t vogue at all, but in the suburbs it’s a whole other level of wild and funny. I said to myself, “I’ve got to do a film or a documentary on dance.” What impressed me the most were the child dancers. There are kids’ dance battles. I said to myself that I had to find a young kid for the film. The thing is, we had permission to film with him for only three days, but it feels like he’s omnipresent.

acting

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was the lack of a script a problem for your dancer-actors?

GASPAR NOÉ — I explained to those who had worries that they should speak in their own voice, in their own way, tell us whatever they wanted, and especially dance a whole lot, and then fool around.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you direct people who knew how to dance but had never acted before?

GASPAR NOÉ — I wanted the filming to be like a game, like a three-week party. Cinema gets everyone excited. Very few people will say no if you ask them to act in a movie. They were all happy. And they were being paid, too. And they were all together in the same hotel, 50 meters from the shooting location. It was like a three-week vacation! Also, I told them we’d all be going together to Cannes. And then the miracle happened: not one person gave us any trouble, not during the run-up or the filming itself or in postproduction, whereas usually there’s always trouble on a film.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There were hardly any professional actors on this film, right?

GASPAR NOÉ — Except for Sofia Boutella, a Franco-Algerian dancer who was the queen of acrobatic hip-hop in France and the United States. She did all the Madonna videos. In five years, she’s done a fair number of films, one of which I saw: Atomic Blonde. I found her really brilliant as a person. Onscreen she’s absolutely fascinating. I placed my trust in her, and she just eats up the screen. There’s another actress as well: Souheila Yacoub. She used to do synchronized acrobatics in Switzerland when she was younger. I met her three days before the shooting started. We brought her in immediately. Both have the two hardest roles acting-wise because they have to go into hysterics. Since they’re both actresses, in addition to being great dancers, they were accustomed to acting and putting themselves into a trance. As for the others, I just encouraged them to take the characters they wanted to play and push them to the nth degree. They chose their own first names.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You question your actors in interview scenes.

GASPAR NOÉ — The idea occurred to us during the filming. I didn’t give any lines, except to the German girl — I gave her something specific to say, to set up a payoff at the end. I told her to say that she’d run away from Berlin, that her roommate put LSD in her eyes, and that she didn’t want to end up like Christiane F. [a German drug addict and prostitute]. I asked the others improvised questions for 10 to 15 minutes and then kept the best replies.

OLIVIER ZAHM — At one point, the girl who makes the sangria says, “Right now, we’re stuck in this school, but there’s one thing I’ve really learned to do in my life, and that’s to make sangria.” But I didn’t understand who was responsible for slipping a mickey into the sangria. The film is very demanding, but in the end you don’t give a damn who did it.

GASPAR NOÉ — I had an idea what people should say, but I didn’t give them exact phrases. The one who’s responsible is the German girl, who claims to have run away from Berlin to get away from drugs. In the last shot, she goes to her room — she’s got Christiane F.’s book, she puts a drop of LSD in her eye, and we fade to white. It’s the German girl, who was really from Bergheim, who pushes the party over the edge. Maybe she was less integrated into the group and secretly wanted to destroy it… Also, in the beginning, she’s with the little Russian girl, who leaves with another one. From the start of the film, even when her friend talks to her, she pays no attention because she wants to see how the party’s going to degenerate.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But, in fact, the person who’s guilty of setting the trap isn’t the trap’s victim.

GASPAR NOÉ — Right. The film’s more about mass paranoia. One little thing goes wrong, and everyone starts running and screaming. There have been plenty of mass hysterias in Paris over possible terrorist attacks. Once people start screaming and running, everyone becomes psychotic. And you’re always hearing tales of people who’ve had something slipped into their drink: GHB or Rohypnol to drug them or steal their debit card. Once people feel they’re losing control and that someone’s put something in their drink, they go nuts with paranoia and get aggressive. It’s like a psychotic state. These days, any little thing will drive a group apeshit. One time, on the second day of shooting, I took out the vodka. We had them drink. Overall, dancers lead a very clean life. They hardly drink any alcohol, so when they do drink, they get drunk really fast. And alcohol will easily put people into an altered state.

story

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s an explosion today in the variety of drugs. It’s unbelievable, compared with the ’90s.

GASPAR NOÉ — And on the Internet, they’ll tell you how to make them. There used to be very few publications on the subject. So, drugs are wreaking greater havoc in the United States now than before. There’s a collective suicide happening in the US. With crystal meth and methamphetamine, there are people making the stuff at home. We’ve learned that lots of young guys have Parkinson’s because of badly cooked drugs. In France, there’s GBL, which is similar to GHB, with effects that are similar but much more violent. And France isn’t even the biggest consumer of the new substances. In Germany, especially in Berlin, people suck it down starting when they’re children.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why do you think there’s so much drug violence today?

GASPAR NOÉ — People want to lose control, as they always have. For years, people would lose control through alcohol. Now, with the Internet, people get stuff by mail order.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Drugs are present in almost every film.

GASPAR NOÉ — Yes, and in many of mine. I don’t make films for or against drugs. It ties into my research on images, on the loss of control.

OLIVIER ZAHM — For you, for your cinema, are drugs a way to fuel narrative, or do they have to do with sensation, or with the image?

GASPAR NOÉ — Irréversible, Enter the Void, Love, and this new one are not, properly speaking, a tetralogy on the stoned youth I know so well. You like to party, too. The world you see when you’re stoned or drunk is different from the world you see when you’re sober. You don’t use the same areas of your brain when you’re drunk or when you’re on coke or LSD. Not only is your perception of the world different, but your personality also changes. I find it interesting to transcribe that into images.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In your cinema — and I think this is your strong suit — the image is a modification of perception. We’re overwhelmed with sensation, an often terrifying sensation. Your latest film is your most difficult psychologically because it touches on the life and the character of a child.

GASPAR NOÉ — I don’t think the world today is any more violent than the world we knew in the ’70s or the ’80s. There was the war in Vietnam, the dictatorships in Latin America. There was violence everywhere in the world, but you felt there was a sort of balance. Today, it’s no longer the same at all. Today, we’re in an ultra-capitalist, ultra-individualist system everywhere, and everyone feels they’re under potential threat. What’s the difference between Russia, the United States, China, and Saudi Arabia? Freedom of expression varies a bit from country to country, but otherwise they’re all ultra-free-market countries where violence is an everyday thing.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I think that today we’ve gotten used to violence because information is ubiquitous and gets to us faster. We’re aware of violence and horrors that at another time might have escaped our notice.

GASPAR NOÉ — To see images of cruelty or violence, you’d watch films that simulated violence, like Cannibal Holocaust and Pasolini’s Salò. You’d say, “That’s horrible,” but you knew perfectly well that it was a representation of reality and that everything was simulated. It’s not the same to see documents or videos on Instagram. It’s true that documents like that are everywhere these days, including hard-core porn. Another thing that really screws with young people’s heads is that there is no longer any erotic cinema or an erotic press. There’s only hard-core porn, which affects children’s view of sexuality. In my opinion, that’s going to change behavior. What drives people to schizophrenia is the omnipresence of social media, where everyone’s competing from childhood on. There are far fewer restrictions on all kinds of images, which seems poignant to me because I didn’t grow up in this kind of world, even if I was fascinated by the images in Salò and Cannibal Holocaust.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In a way, cinema’s symbolic representation of cruelty and extreme violence protected us from that because the spectator knew it was a representation, a use of symbols.

GASPAR NOÉ — I don’t think so. I was re-watching Irréversible this morning, and I don’t feel that my new film is more violent. On the contrary. I think it’s funnier, more scenic.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Thinking about sensation: how do you translate a person’s modified perception into an image?

GASPAR NOÉ — Every film is different. In I Stand Alone, it’s cut up into still shots, wide angles, and close-ups, almost like a Yasujirò Ozu film. Later on, I felt like changing. When I made Irréversible, I said to myself: “Hmm. This time, we’re going to have a camera that’s always in motion.” When I made Enter the Void, I really wanted to reproduce the perceptions of someone in an altered state of being, on acid, even if only in a two-dimensional way.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And in Climax?

GASPAR NOÉ — In Climax, the camera is like a fly wheeling around the characters. Early on, I wanted the film to be like a documentary, but I couldn’t resist doing a few fairly basic effects, like flipping the picture upside down, to create a sense of queasiness. I also included a lot of sub-bass sound in the second part of the film. People like to have sub-bass when they dance, but sub-bass channeled into a movie theater can be pretty unsettling.

filming

OLIVIER ZAHM — You follow the characters around with a handheld camera. Do you do the shooting yourself?

GASPAR NOÉ — On Irréversible, I was the cameraman. On Enter the Void and Love, I shared camera duties, depending on the sequence. On this film, I said to myself, “I have to stick right to the characters.” And since we were also filming chronologically and without any written lines, it was good to be a meter away and be able to intervene with stuff like: “You’re out of frame,” “Repeat the line,” or “Get angrier.” I could give direction, and, of course, I cut myself out in sound editing. We shot with a shorter focal length than what you see in the film, which allowed us to stabilize the picture a bit in postproduction. It’s like taking a fisheye and scope-framing inside it. If the camera shifted because it was being carried, we could always recover and stabilize the image in postproduction.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You didn’t use a Steadicam?

GASPAR NOÉ — No! People say, “Yes, you made the whole set piece at the start of the film with a Steadicam.” No. I did it with a handheld, and we stabilized the picture. The film critics were astonished that the camera was always in the right place. They were intrigued by the elegance and fluidity, which we actually achieved in postproduction. In the second half of the film, however, I felt like getting the camera to tremble. The picture starts to waver, just like the characters.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It can be said that you’re brilliant with the camera because all your shots are well done.

GASPAR NOÉ — I was always a meter and a half from the characters and worked in tandem with Benoît Debie, who hung all the lights from the ceiling, with high-wattage bulbs that were all remotely adjustable. He could change the intensity from an iPad. So, he’d have fun playing with his iPad, and I’d have fun playing with my camera.

sound

OLIVIER ZAHM — Hence the intimacy we feel, as if we’re actually among them. We hear their breathing. Is the sound coming directly from the camera?

GASPAR NOÉ — For most of the film, the sound is direct, but there are still quite a few lines that vanish beneath the music. We had a boom, and sometimes we used lapel mics, too. So, there was some post-synching to be done. We didn’t change any lines, though, and between takes, we’d have the dancers dance, with the music going full blast. But when we were filming, we’d put out a version with just the sub-bass, so you’d have the beat of the music dissociated from the mid-range and treble frequencies. So, when people talked, they’d talk over an ersatz music that was easy to take out in postproduction, and we’d recover their voices. Later, we’d put the music back in, so the guys talking are using their real voices. It’s direct sound. That allowed people to dance to the rhythm, and us to recover their voices.

setting

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why did you set the film in the 1990s?

GASPAR NOÉ — If you tried to film Climax in 2018, half the film would just be people shut into their room, or in the bathroom sending out text messages every second. That has utterly changed human relations. Last year, I saw Michael Haneke’s film where the characters always communicate by SMS. So, you say to yourself, “It’s strange, but today, when you put together a story, you have to have a close-up of a cellphone.” For one thing, it’s very dated. And then it’s not really cinematic. Making a film with dancers is super-cinematic.

closed set

OLIVIER ZAHM — Has someone ever slipped you a mickey?

GASPAR NOÉ — Yes, but generally it’s not done with ill intent. Whether you’re in Paris or New York, it’s in your best interest to pay attention to what you consume. Even with joints. Because when someone passes you a joint, it could be skunk or it could be something more violent than LSD. You toke and feel like your head’s become a flying saucer.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But how did you come up with the idea for the hell of an enclosed space? Because once we enter, we’re trapped inside until the police arrive. You almost feel saved, almost glad to get back to reality. Because in your film, we don’t know just how far things can go. It feels like there are no limits.

GASPAR NOÉ — When the door finally opens at the end, it feels like your mother’s vagina dilating to let you out. Maybe the world ahead, the world of oxygen and burning light, is no better than the other, but you want to get out.

genre

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you know that there are people who are scared to see your films? Somebody must have told you that.

GASPAR NOÉ — Absolutely. The film is anti-oxygen, and even more so in the theater, where you really take it in the face. When you watch it on TV or on DVD, you’re in control. You’ve got the remote, and you feel safer. In any case, most of the people who see my films don’t see them in theaters. They’re not hits in the theaters. Most of the people I run into — every day — who talk about my films have seen them on computers or on remote-control TVs.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You manage to compete with the banalization of the image or of violence. You manage to top banalized violence.

GASPAR NOÉ — Violence and cruelty are inherent to life. I think the Internet’s arrival has had an effect on commercial cinema and on the arts. Since images of extreme violence are much easier to see in our everyday lives, people no longer want to see violent images at the movies. The films that are pulling in the most people right now are silly comedies or general-audience science fiction, like Star Wars, which has reached a point where people die without us seeing the light-saber run them through. Mission Impossible doesn’t have a single violent image in it. People die, but you never see a drop of blood. I think that with Sept. 11 and the Islamic State and all the nuclear threats, people are scared there’s going to be a third world war, especially people who have children. It’s becoming taboo. But it’s true, too, that most world leaders are far more belligerent today than they were 20 years ago.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you manage to produce a cinema that talks about all that, that shows how a very simple, banal, everyday thing can degenerate and become a metaphor for a world that can spin out of control at any moment.

GASPAR NOÉ — I don’t trust portable computers and cellphones because they get buggy right when you least expect it. Sometimes it’s your computer that goes on the fritz, or else you need to call someone and your cell fails you right when you need it most. Everything is so centralized, automated, and computerized that it seems like war could break out over a technical glitch. Now, if the film comes across today as being symbolic of this phobic state, well, it’s really not by design. At the start, I was thinking of it more as a disaster film, like the ones I’d watch as a kid — The Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure, or George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, where zombies attack people at a supermarket. I wanted to make a disaster film, like Titanic…

END

SOFIA BOUTELLA IN GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018 COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

SOFIA BOUTELLA IN GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018 COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

ALL THE DANCERS IN GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018 COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

ALL THE DANCERS IN GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018 COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

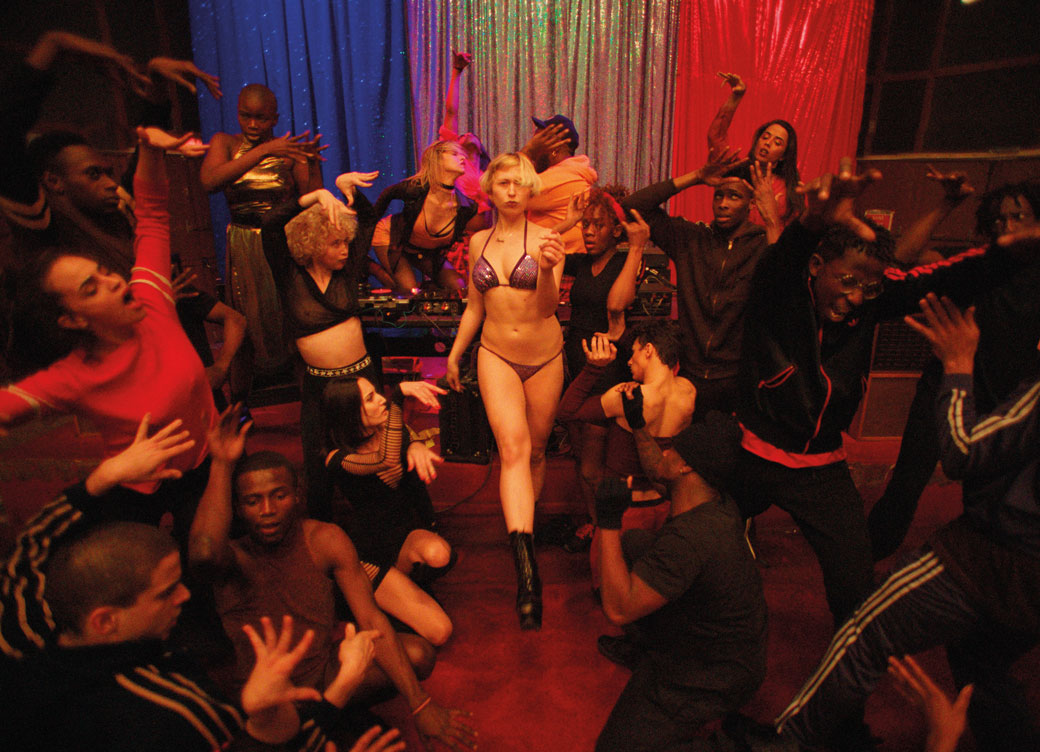

THEA CARLA SCHØTT WITH THE CAST OF DANCERS FROM GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018, COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

THEA CARLA SCHØTT WITH THE CAST OF DANCERS FROM GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018, COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

ROMAIN GUILLERMIC AND SOFIA BOUTELLA IN GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018, COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

ROMAIN GUILLERMIC AND SOFIA BOUTELLA IN GASPAR NOÉ’S CLIMAX, 2018, COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

GASPAR NOÉ PLAYING IN A SCENE FROM HIS FILM CLIMAX, 2018, COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH

GASPAR NOÉ PLAYING IN A SCENE FROM HIS FILM CLIMAX, 2018, COPYRIGHT RECTANGLE PRODUCTIONS/WILD BUNCH