Purple Magazine

— F/W 2009 issue 12

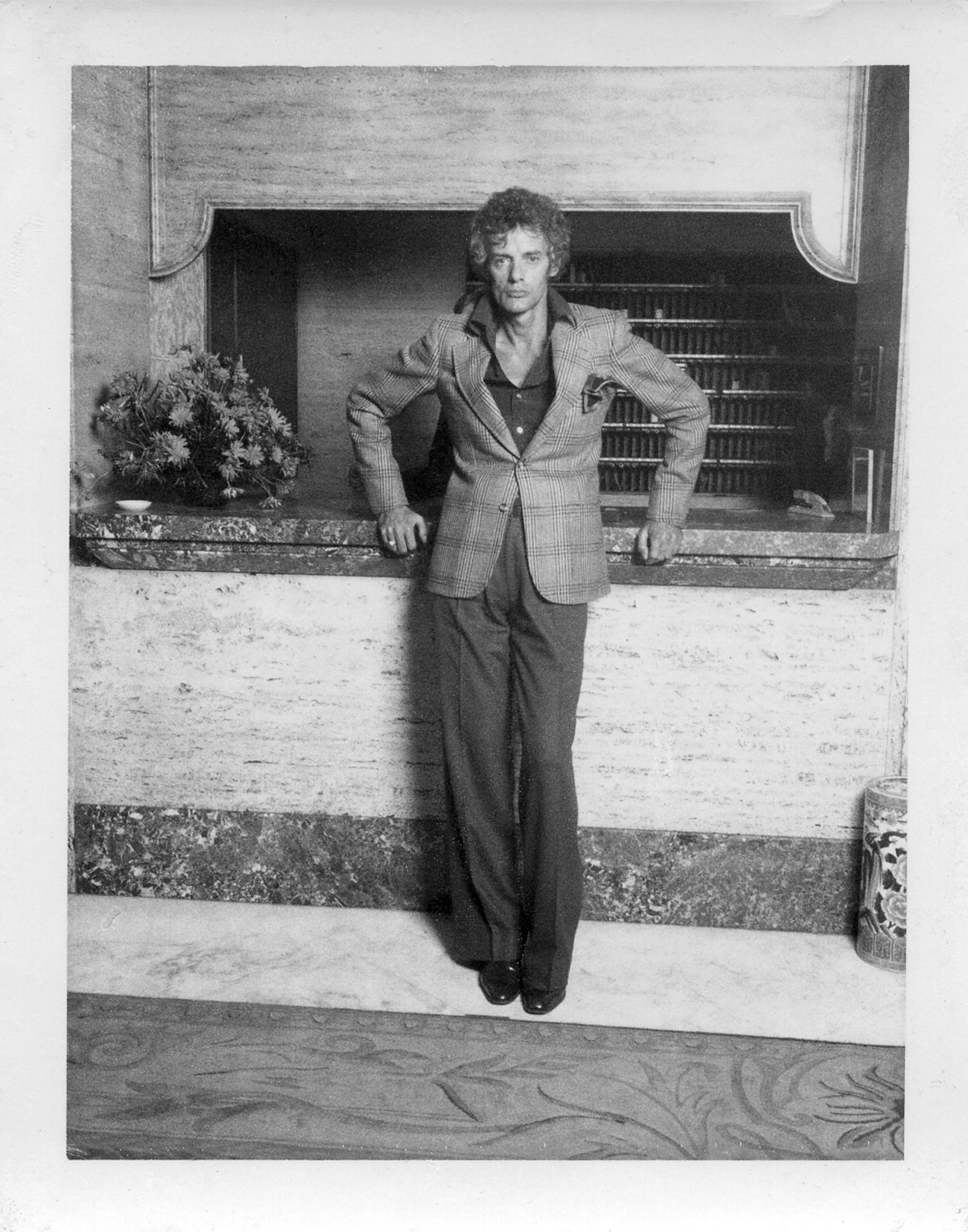

Terry Richardson’s Life Story

Terry Richardson in Hollywood at age 9, 1974, photo Annie Lomax

Terry Richardson in Hollywood at age 9, 1974, photo Annie Lomax

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

TERRY RICHARDSON’S LIFE STORY

EPISODE 3

Age TEN

to FOURTEEN

OLIVIER ZAHM — The last time we spoke you began telling me about your mother’s violent accident.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yes. It happened in Hollywood. I was waiting for her to pick me up after a therapy session. But she was in a horrible car accident and never showed up. She was in a coma for a month and suffered permanent brain damage. I always felt weird about it even though it wasn’t my fault.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You felt guilty?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Absolutely. I was only a mile or so from home and I could have walked. I waited for about three hours and I had a really bad feeling, thinking something awful had happened. She never showed up — another big abandonment. She would never be the mother I had known again. Eventually this woman named Vicky came to get me. She told me that my mom was in the hospital but that she would be OK. I went back home and my stepfather was there. Then I went with my mom’s friend to see the movie, Rollerball, with James Caan. I was only nine and didn’t fully understand what was going on. I wasn’t allowed to see her for three months because they didn’t let children into the intensive care ward. But I had my stepfather and my friends in our building. My friends’ moms looked out for me and my grandmother was there. I don’t remember all that much about that first month. She spent a total of six months in the hospital. I think I just kind of shut down and pretended everything was fine. I was in a kind of denial. It was such a shock, so abstract — my mother not being there — that I couldn’t acknowledge it to myself. When I finally did see her it was the weirdest fucking thing. She had lost some of her vocal chords and couldn’t talk clearly and she couldn’t walk. She was like a crippled person. She was all fucked-up, drooling, and in diapers and a wheelchair. I tried to hold her.

I was horrified, thinking, “Who is this?” She was a fucking mess, just hurt so badly. I was so upset. Like, “No, this can’t be happening! Where’s my mother?” A child just can’t deal with things like that. I just didn’t understand.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I imagine that it was probably very traumatic for you to see your mother suddenly become like an old woman, and to feel like you had to become an adult overnight. Plus, your real father wasn’t around either. You must have felt orphaned, in a way.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yes, I did. My stepfather was great — he always let me do what I wanted — but I didn’t have the kind of supervision a father should give his child. So I basically shut down, losing my mom at such a young age, and I know that a lot of my issues — like those with women, for example — stem from it all. It affected my mom emotionally as well. She was high-strung to begin with, always very independent, and now she was trapped in a body that she couldn’t move. So she was very angry. I remember hearing all these crashing sounds in the middle of the night — she got up ot look for a cigarette and fell over a table. She was screaming, “Why did I come back? I just want to die!” It would happen every time she fell over or was in pain. When you’re a child and your mom is telling you she wants to die, you think, “But what about me? You have to take care of me!” It became all about her. She was just so unhappy and in so much pain.

Terry Richardson with his mother, Annie Lomax, and father, Bob Richardson, in Hollywood, at age 10, 1975, polaroid Jackie Lomax

Terry Richardson with his mother, Annie Lomax, and father, Bob Richardson, in Hollywood, at age 10, 1975, polaroid Jackie Lomax

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did your real father react to your mom’s situation?

TERRY RICHARDSON — He came out and visited her but I don’t really remember his reaction. I’d go out and stay with him in the summers.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Is that when you started to smoke weed?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yes, the summer after my mom’s accident I smoked weed for the first time with my friends in Woodstock. One of them stole weed from his parents. I remember getting stoned all the time, laughing and falling. I remember feeling so great, feeling so free. I could finally escape.

It became my new candy.

OLIVIER ZAHM — When did you start to be interested in girls?

TERRY RICHARDSON — I remember going to Haiti with my father when I was nine or ten, to a hotel a friend of his owned. There were these two young models there, one really skinny and the other really voluptuous with really large breasts. I was obsessed with the voluptuous one — I’d bounce into her in the pool and try to grab her boobs.

I just fixated on her. She was like 20 or something and I was like ten. I had such a big crush on her. I actually saw her in the shower once, and she said, “Come here. You can look at me.” It was a really intense moment, looking at this woman and then rubbing soap on her and stuff.

I was barely ten years old, not yet a sexual being. I was freaking out, totally embarrassed. It was crazy — almost like being molested, in a way. But I stuck around, of course! [Laughs] I couldn’t come or anything — my balls hadn’t dropped yet. [Laughs] It was the weirdest thing, to be attracted to her sexually but unable to actually have sex with her. I mean, it’s not normal for a ten-year-old boy to touch a woman’s breasts. And she liked it!

OLIVIER ZAHM — What was it like visiting your father in New York?

TERRY RICHARDSON — I’d visit my father at his place at the Gramercy Park Hotel after Anjelica Huston left him. I was like seven years old. She put all her stuff into a bag and walked away from him and they never spoke again. She and my mom actually became good friends afterwards. Anyway, I’d go on shoots with him and we’d go see movies together. I remember at the end of Taxi Driver he put his hand over my eyes to keep me from seeing all the blood and gore and I moved it away. I saw a lot of sex and violence in movies when I was very young. But after hanging out with my dad in the summer, seeing my mom again was really heavy. She was undergoing physical therapy — she could walk with a cane but she still fell over a lot. But she was so fucking strong — she’d struggle down to the supermarket and back with a shopping cart. Or I’d hear her going up and down the stairs one step at a time, making this clunking noise, to get my stepfather a cup of coffee. It was incredible — she’s such a survivor. Just kept persevering. She’d freak out sometimes but she kept going. And she’s still going. Her spirit and her will to live and do the normal things in life — it’s amazing.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s beautiful.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yes, it is.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where you able to leave the family house and go out on your own?

TERRY RICHARDSON — I was hanging out on Hollywood Boulevard, skateboarding and biking around. The street was incredible back in ’75, ’76 — the runaways, the prostitutes, the drug dealers. And all the cool cars. It was the Wild fucking West. I was cruising around at night, hanging out at head shops, playing pinball for hours and hours. We lived four blocks above Hollywood Boulevard and I’d head down on my skateboard and hang out with my friends. We also played baseball and stuff. And we’d sneak into movies — I remember seeing Russ Meyer’s Beneath the Valley of the Ultra -Vixens with all those actresses with the huge breasts. But oftentimes we’d get kicked out. [Laughs] I always loved movies. I’d go by myself, even when I was young. I’d go to three in a row. It was an escape for me. I’d go every weekend.

Terry Richardson and his stepsister in London, at age 9, 1974, photo Annie Lomax

Terry Richardson and his stepsister in London, at age 9, 1974, photo Annie Lomax

OLIVIER ZAHM — How was life for you at school?

TERRY RICHARDSON — At that time I was always getting into fights at school. I lit cars on fire and smashed windows — general vandalism. And I’d always be talking on the phone for hours with girls I had crushes on. It’d be, “Get off the phone!” When I was nine, ten, 11, I had long hair and I was really pretty. People thought I was a girl.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I had long hair when I was a kid, too. I remember being so sad when I had to get it cut. Seeing these kinds of movies at such a young age must have been important to your future development as a photographer, along with the fact that your mother and father were photographers.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yes, most kids didn’t see those kinds of movies. I did because my dad took me. But I was always really drawn to sex and violence. They had all those porn-film theaters on Hollywood Boulevard, like The Pussycat Theater. It was a bit like Times Square. I remember seeing a still from a movie of a guy tied-up on a bed with a really sexy blond sitting on him holding a clear plastic bag over his head.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Wow! So you could see the face of the guy.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah, being strangled. I was obsessed and aroused by this image. Her being so overpowering and dominating seemed so sexy to me. But I never saw the movie. It was X-rated and I could never get in. I was only ten or 11. But I was obsessed with that image. And then I read a story in a magazine about these girls who escape from jail, overpower this guy, torture him, and drive a stake through his balls. I remember being so turned on by that! [Laughs] Then there was the scene in Sam Peckinpah’s Cross of Iron, with James Coburn, that has these soldiers raping and pillaging in this village — this guy forces this girl to give him head and she bites his cock off.

The sleeve for the Jackie Lomax album, Living for Loving, shot on Venice Beach, California in 1975 by Doug Metzlerin. Portrait of Jackie Lomax by Annie Lomax.

The sleeve for the Jackie Lomax album, Living for Loving, shot on Venice Beach, California in 1975 by Doug Metzlerin. Portrait of Jackie Lomax by Annie Lomax.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I know that scene!

TERRY RICHARDSON — It blew my fucking mind! It was so intense for me! Why was that? What does it all mean? — Fear of castration, maybe? — Castration complex?

OLIVIER ZAHM — Yes, and at an age when you weren’t even having sex.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah, it was already all over for me, right? I was a mess even before I started having sex! [Laughs] But what does it mean to have responded only to images like that? Gimme a little French intellectual psychology, Olivier! Basically, I responded most to images of physically strong, overpowering women, right?

OLIVIER ZAHM — Well, as a child the source of violence against you came from women. First you lost the presence of your father in your life because of a woman — a woman took him away from you. You saw that the power of a woman over him was stronger than his love for you. Then your mother ceases to be your mother, in a way, after her accident, taking mother-love away from you. You came to equate women with violence.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Wow, that was good! Usually I don’t understand that stuff! [Laughs] I also loved that scene in the James Bond movie, Diamonds Are Forever, when Sean Connery gets attacked by those two girls, Bambi and Thumper, who use kung-fu on him. He finally wins the fight, but they really kick his ass for a while there, this black girl and this white girl, and it really turned me on, really aroused me. Really sexy scene. Maybe

I should do a series of pictures with women overpowering men.

OLIVIER ZAHM — We’ve seen similar images of super-powerful women in Tarantino’s movies. Like in Kill Bill, when Uma Thurman’s character kills the character played by David Carradine, who actually just died.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah, autoerotic asphyxiation. It’s hard to understand. He was 72 years old. They found him alone with a cord tied around his neck and one around “another body part.” And they didn’t mean his feet. But, getting back to my responses to pain, it’s emotional pain more than physical pain that I respond to. I mean, if someone pinches my nipples or scratches me, it just hurts and I don’t like it. But I like emotional pain.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Let’s go back to your memories of life in Hollywood in the mid-’70s

TERRY RICHARDSON — I went to Cheremoya Elementary School on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood. It was crazy — there were gangs and you’d get followed by weird older guys. Hollywood was a seedy, sleazy town. You had the Greyhound bus terminal on Sunset and Vine and people would come in from all over America with their dreams to make it in Hollywood as actors or musicians or whatever. You’d see the pimps and the thugs literally waiting for that young girl or boy they could take advantage of somehow. There was a coffee shop called The Gold Cup at Las Palmas Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard and a newsstand on Las Palmas where 14- and 15-year-old boys would hang out and wait for older guys — chicken hawks — to pick them up. The boys may have been a little older, 18 or 19, but I still remember thinking, “What are all these kids doing here?” It’s strange for a young kid to see that stuff. But it was ’70s California street life — hippies, weed, and prostitutes. But then there was cool stuff like The Source, the trendy health-food restaurant on Sunset. Everybody ate there, Warren Beatty and everyone. Woody Allen shot a scene for Annie Hall there — “What are these, sprouts? What kind of food is this?”

Grade 4 school portrait in Hollywood at age 10, 1975

Grade 4 school portrait in Hollywood at age 10, 1975

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did your mom start getting better?

TERRY RICHARDSON — My mom always had friends who would come and take her out for lunch or to the beach, just to get her out of the house. Before the accident she was really into Transcendental Meditation. I went to the T.M. center in Santa Monica and got my mantra. My mom tried to get me to do yoga when I was about six,

but I was like, “I’m a hyperactive kid on a bunch of candy! I don’t want to do yoga!” But the T.M. people told me I could walk around in a circle in my room when I meditated and I really did, everyday! Chanting my secret word. I can’t tell you what it is — it’s mine, you can’t have it! [Laughs]. Anyway, I was doing all the meditating and eating all the health food when I was a kid.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you still meditate?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Well, it’s funny — the other day I asked a friend why he was so mellow and he said it was because he had been meditating for five years. I thought maybe I should try it again, because it’s really beautiful to meditate,

to just sit quietly and clear your head. Answers come to you.

OLIVIER ZAHM — David Lynch is totally into it. He wrote a book about it. He can’t live without it. It’s an inspiration for him.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Well, images probably come to him when he meditates, or just afterwards. It’s great for people. It’s relaxing and peaceful. You can erase your thoughts and clear space for new ones, which is beautiful. Our heads get so jammed up with bullshit and drama and chaos. Meditation can wash that all away.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Living in Hollywood, did you dream of becoming famous?

TERRY RICHARDSON — I wanted to become an actor for a while, but because I was so shy it was really hard for me. I wasn’t a stage kid. I’d get really withdrawn. But, I was modeling — you know, my mom was also a stylist and she would hook me up — and I read for a movie, which I didn’t get. I did get to a final call for a commercial once.

All I had to do was recite the line, “Milk helps me navigate.” They were like, “Say it like a pirate would!” But I choked, I panicked, I froze. Paralyzed by fear. I just couldn’t fucking do it. I was traumatized! [Laughs] It could have been the start of my acting career! I auditioned for The Bad News Bears, which I loved. But I didn’t get it. God, it could have turned out really badly for me if I had become a successful child actor.

Bob Richardson on a job in New York in 1977

Bob Richardson on a job in New York in 1977

OLIVIER ZAHM — I imagine it started to be a hard time for the family money-wise.

TERRY RICHARDSON — My mom was working constantly before her accident, styling, taking pictures, and then it all just stopped. And she was only 36. It must

have been really hard for my stepfather, Jackie Lomax. There wasn’t much money coming in. We were on welfare. We’d go to Burger King. My mom was allergic to the sesame seeds they put on the top halves of their hamburger buns so it was always a scene ordering for her — “Yeah, give me a burger with two bottom halves of the bun.” “What?! We can’t separate the buns!” [Laughs] So I’d say, “Gimme two burgers without the top halves of the buns, then.” It was like that scene in Five Easy Pieces with Jack Nicholson yelling at the waitress. My mom would try to cook but it was horrible. My mother’s mother moved from Miami, where she had retired to after being a beautician in Queens, to LA to help out, but my mom couldn’t stand her and was really cruel to her. “She makes me fucking crazy! Get her away from me!” And my grandmother would be like, “What did I do? I just love you.” But thank God for my grandma. She would buy me clothes and ice cream and she helped us out financially. We were actually living on the poverty line. I love my grandma. Without her it would have been a lot worse. She lived in Sherman Oaks in the Valley in her cousin Peggy’s house.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Were you able to get a settlement from your mother’s accident?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yes, because my mom’s car was hit by a Pacific Bell Telephone truck we figured we could sue them. It was such a fucked-up thing. We thought we’d get millions of dollars. My mom’s life was destroyed, I didn’t have a mother — it should have been a huge settlement. They offered to settle out of court and give us a half a million. Keep in mind that the lawyers take 25 or 30 percent. To sue them would have taken three years. So Jackie, who was the legal guardian, decided we should take the money instead of fighting the case. I had to sign a thing saying I wouldn’t sue them after I turned 18, even though I was still a child. I resented Jackie for the fact that we only got about $300,000 after the lawyers took their cut. I got $17,000, which was put into an annuity that gave me $5,000 for five years. It’s crazy to think that your mother’s life is destroyed, and yours too, in a way, and you only get $25,000. I was really upset.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That’s the value of life in a capitalistic society.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah. My mom has been struggling ever since. I help out, of course, but it’s been hard. And here it was one of the biggest companies in America, a fucking phone company — we should have gotten ten million dollars. We should have had a nurse and a house, all that stuff. It was a joke. But I understand that Jackie was desperate for money and just took their offer to settle out of court. Anyway, sometimes I’d spend weekends in the Valley with my grandmother, hanging out, playing pinball, batting baseballs around. Her apartment building had a pool and I made friends with some of the kids around. It’s funny how you can do that when you’re nine or ten, just make friends. You don’t do that when you’re older, just make buddies with someone at the beach and play with them. Doesn’t happen.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You said that you became violent around this time.

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah. I started fighting more than ever after my mom’s accident. I was angry. I was hurt. To hit people, to be hit — physical pain — was a way to get out of myself. I took karate and I was a pretty good fighter. I wish I still took karate and was an eighth degree black belt. I loved it. I loved Chuck Norris. I had Bruce Lee posters on my bedroom wall. All us kids were mad about Bruce Lee — Enter the Dragon, Fists of Fury and Chinese Connection. Five Fingers of Death by the Shaw Brothers was the first kung-fu movie that came to America. The main thing about it was that the guy could pull out your eyeballs with his fingers. I asked the director of the movie theater where I saw it in Woodstock if I could have the poster for it and I put it up on my wall. The graphics of the posters were always great — really colorful, with guys fighting and some hot Asian girl. I took karate lessons from Tak Kubota on Sunset Boulevard across from Hollywood High. He was in Sam Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite, with James Caan. He was a Japanese seventh degree Shotokan Karate black belt. I advanced really quickly and at ten or 11 I was fighting older kids. Nobody my age would fight me. But I got beaten in a fight in front of a lot of people and it embarrassed me so much that I never went back. This older kid hit me and I started crying and I was too humiliated to go back to class. So basically it was all just one traumatic experience after another. [Laughs] But it’s funny, all these little things that trigger the fears and anxieties we all have. Like, when I trip on something on the sidewalk I get embarrassed and really self-conscious for a second or two. But out of all the kids I fought at elementary school, the only one I ever lost to was this giant eleven year-old Polish girl, Stella Kolatsky. She was huge, like a football player. [Laughs] She punched so fucking hard she knocked me out cold! I didn’t see it coming. My face was all numb. I saw stars! But we became friends afterwards — I’d go to her house and have peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and stuff. But everyone knew a girl had knocked me out.

Terry Richardson in Hollywood, at age 12, 1977

Terry Richardson in Hollywood, at age 12, 1977

OLIVIER ZAHM — Another humiliation!

TERRY RICHARDSON — Yeah! Being totally overpowered by a woman — I probably fell in love with her! Stella Kolatsky — I never forgot her, man. Right hook — BOOM! Literally knocked me right off my feet. Right in the fucking schoolyard.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There must have been some good times, though.

TERRY RICHARDSON — When I was ten I had a great experience at The Lazy J Ranch Camp in Malibu. It was one of the best summers of my life. Swimming in the pool, going to the beach, riding horses, barbecuing food, playing softball with all these kids — it was great. I’d get care packages with all this candy. We were allowed one soda a day. They had a machine with Welch’s grape soda — that stuff was so good. It was beautiful being at camp with all those kids. I remember that “Crocodile Rock” by Elton John was really big that summer. [Sings] “I remember when rock was young…”

OLIVIER ZAHM — But you never really got into surfing, did you?

TERRY RICHARDSON — No, I was too much of a street kid. When my friends started getting into surfing, when they were 12 and 13, I was getting into punk rock, hanging out on Hollywood Boulevard, getting into drugs and alcohol. At 13 I preferred to hang out on the street and sell weed and party. I’d go to the beach to party — meet girls, smoke weed, and drink beer. But I never got into the athletic thing and surfing.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I’m surprised that you didn’t get into more trouble with such little supervision.

TERRY RICHARDSON — I remember this friend of my mom trying to kiss me — I mean coming on to me sexually — when I was really young. I was a really beautiful kid and people were attracted to me. I remember being in the supermarket and people inviting me to their houses, or to go for a drive with them in their car and smoke some weed. But I always knew better than to get in a car with strangers. One time when I was visiting my dad in New York this very beautiful model came on to me at a movie. Put her arm around me. I also remember watching the TV show, Baretta, at the Gramercy Park Hotel in ’76 or ’77 and the lights all going out. It was the big blackout. There was all this looting going on. Absolute chaos. And Son of Sam, the killer, was still at large. The next morning I was in the bar downstairs having a Shirley Temple and this handsome young guy in a suit asked me if I had ever been up on the roof of the hotel, that the view was really nice — trying to get me to go up on the roof with him. Something told me not to do it. I have memories like that, of being threatened sexually, of being in imminent danger. I’m grateful that I knew not to do certain things because some kids don’t. There was always this weird stuff with men and women — because I was so pretty, I guess.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s good that you had that instinct of self-preservation. How did you feel about New York when you were that age?

TERRY RICHARDSON — I felt it was similar, in a way. I hung out on Eighth Street and I’d go to The Eighth Street Playhouse and see The Song Remains the Same and The Ramones movie, Rock ‘n’ Roll High School — I saw that movie about 50 fucking times! I was obsessed with The Ramones. Even before I got into punk rock I loved The Ramones. I remember hanging at Bleecker Bob’s, the record store, and on Eighth Street, and at Washington Square Park, and cruising around on my skateboard. In the ’70s people hung out in the West Village. On Eighth Street there were record shops and head shops that sold hash pipes and bongs. St. Mark’s was cool, too. I’d go with my dad to Paul McGregor’s Haircutter, which was a really groovy place. I used to get really good, expensive haircuts there. Hair salons were cool back then — people hung out, partied, did drugs: it was a scene. But where everyone really hung out the most was on Eighth Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, and on Bleecker Street, west of Broadway and over past Sixth Avenue. There was nothing in the East Village back then except CBGB over on the Bowery. There were random parties that I was too young to go to. But the main scene was in the West Village. Eighth Street was like Hollywood Boulevard for me. You could buy weed or pills or anything you wanted and you could hang out in Washington Square Park — it was great. They had late night showings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show where people would dress up in the costumes of the characters and act out the whole fucking thing. It was one of the original midnight-movie showings and people would drink and get high and watch the movie over and over again. It was a great time: great music, great weed.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you ever steal things, like many children do?

TERRY RICHARDSON — Oh yeah. When I was nine, ten, and 11 I would steal clothes — pants, shoes, shirts. I loved to steal. I didn’t get caught until I was 13. But that was later on, when I was getting high and stuff.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The ’70s are known for being a time when people had great sexual freedom. You must have felt some of the excitement in the air.

TERRY RICHARDSON — I was too young for the sex. I was just a kid. I remember I used to steal panties from the laundry room. There was this dancer in our building who I fantasized about having sex with. She was probably 27 or 28. I used to steal her dirty panties and sniff them while I masturbated. Then I started stealing pages of pictures of girls out of magazines to masturbate to. I thought it would be less serious if I got caught stealing only the pages and not the whole magazine. I would look through the magazines until I found one I liked well enough to steal. I had stacks and stacks of pages ripped from porn magazines! All of girls with hairy pussies. Hey, it was 1976: hairy pussies. And nice big breasts. I was in my room masturbating, all the time. Or up on the roof of my building. Every chance I could. I had wet dreams every night and I masturbated all day. I mean, you just can’t stop!

OLIVIER ZAHM — What was your first real sexual memory?

TERRY RICHARDSON — I clearly remember the first time I came. I was 11 or something. I was in the shower and I touched myself and all of a sudden stuff squirted out. It freaked me out! I got scared. I didn’t know what it was. I was touching myself, going, “This feels good, this feel good.” Then, “ahhh!” Flames might as well have been shooting out of my dick! I didn’t know what the fuck it was. It’s very intense, your first orgasm. You never forget that.

[TO BE CONTINUED]