Purple Magazine

— F/W 2015 issue 24

André Saraiva

Tags by André Saraiva and Axone in Belleville, Paris, 1989

Tags by André Saraiva and Axone in Belleville, Paris, 1989

street credibility

interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

portrait in André’s New York studio by MARCELO KRASILCIC

André is a brand. André is the night. André is everywhere. My 10-year-old daughter knows and loves André. André redesigns clubs, hotels, and restaurants for night people across the planet. He’s a nonstop DIYer, collaborating with fashion brands, exhibiting in art galleries and museums all over the world, taking pictures, and making films. André never stops… So where does he come from? Who was he before his success? He started as a tagger, putting his tag everywhere, as much and as often as he could, as high up and as visible as possible, so that the public services can’t remove it. In that sense André is faithful to himself: self-promoting his identity, not for the sake of himself or for the sake of becoming famous, but to prove to himself and to everyone that the street is the starting point, the real theater of life, at the same time a utopia and a dystopia where you can write your own story.

Paris subway, early ’90s

Paris subway, early ’90s

OLIVIER ZAHM — You spent yesterday evening in your New York loft rewatching one of Éric Rohmer’s films, from the

Contes Moraux series. Was it nostalgia? You said it mirrors the slightly depressing love stories found in Michel Houellebecq’s

novels. And you said that, in the end, what comes up is the image of a rather mediocre France…

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, it’s sad; it’s extremely sad. Especially seen from New York, where I have now mostly settled.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You don’t feel too French any more, yet you can step right back into that Rohmerian sensibility.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, I recognize the aesthetics and the feelings that develop. I experience them more as a foreigner,

because I only arrived in France in 1981.

OLIVIER ZAHM — At the same time socialism arrived.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, with François Mitterrand as president. At the time, my mother was in love with a Frenchman. She

must’ve thought it was an incredible moment, that it was going to change our world a little.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You had come from Sweden, right?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes. And I had to attend a French elementary school. I felt like I was living through Truffaut’s 400 Blows. It definitely was archaic — compared with Sweden, it was underdeveloped. I was 11, I was telling my classmates about sexuality, and what a pussy looked like because I had already had classes in sexuality. In any case, the school administration and the teachers were not happy with my little lectures. But I made a lot of friends. I was well liked.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where were you?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — In the Marais, but at a time when the Marais was still a real working-class neighborhood. It was dirty. The facades of the buildings had not yet been renovated; they were all dark. It was a Jewish working-class neighborhood with a couple of intellectual architects and some post-’68ers, who were beginning to move in. It was the beginning of the gay bars. And, in any case, it was a very mixed, working-class area back then, in the heart of Paris.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So your move to France went well?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Not at all. I hated it. I found everyone extremely mean. My French was pretty random. My parents thought it would be a good idea to put me into a public school, but in fact they didn’t have the money for me to go elsewhere. So I learned on the ground, as it were.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your parents are Portuguese. Why were they in Sweden?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — They escaped from the dictator Salazar in 1969-70. My father deserted from the Portuguese Army. He had to sell his guns and his rifle to cross the border. And then they met up in Paris. From what they’ve told me, they made me in Paris, on the Rue Dupetit-Thouars. That’s what my mother said. [Laughs] So I was literally created in Paris.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You are “made in France.”

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — But my mother loved Ingmar Bergman’s films, and she was very into Sweden, which at that time was letting in a lot of political refugees. They went to continue their studies in Uppsala, where there is a big university. And I was born there.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you have nice memories of your childhood in Sweden?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Uppsala is an old university town north of Stockholm. It has one of the oldest universities in Europe, and incidentally it’s where Bergman was born. So I grew up in this old Swedish town, in working-class neighborhoods. And it was an extremely evolved country, socially speaking, a paradise for children. Even if I was the only kid with dark hair in the midst of thousands of blond kids. My passion for blondes must come from those first impressions. I’m sure my first “playing doctor” sessions and my first loves were little blonde angels.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You didn’t feel rejected?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — They would call me svart khäli, which translates to “nigger head”…

Tag in London, early ’90s

Tag in London, early ’90s

OLIVIER ZAHM — Charming!

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Right? But all my life, I was only partly accepted in the countries my parents were dragging me to, so I think I was — even way back then — fighting, attempting to prove myself, to be accepted. I also developed, inversely, an amazing ability to make friends in all sorts of circumstances. I do have good memories of Sweden. It’s funny but, even today, most of my favorite tastes, the dishes and the things I like, come from Sweden — along with the lovely blonde women.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In any case, it definitely affected you. Do you still speak Swedish?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I speak a rather childish Swedish, but I do speak it, which flips people out around me. The Portuguese Saraiva who speaks Swedish! [Laughs]

OLIVIER ZAHM — You had a facility for making contacts. It’s a trait we recognize in you. Maybe it’s because you knew you had to find a place for yourself.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I always felt a little left out and not in my “place,” whether it was in Sweden or in France, where I felt it even more, and in Portugal where I go regularly. Even today, in New York, which is the most open city in the world… Children are quite cruel to each other. As a young street artist, I was more often in contact with older people, different people, exiles, displaced people, travelers, artists, slightly sketchy people of the night. I’ve always been attracted by outsiders; they accepted me much more quickly than the others. And I discovered that they also had the most interesting personalities, which has always been a source of curiosity for me. I am sincerely curious about other people.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You spoke Portuguese with your parents?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — With my mother, I spoke Portuguese.

Black Kubrick by Mr. A, edited by Medicom Toys, and Mickey, edition of seven, at André’s New York studio

Black Kubrick by Mr. A, edited by Medicom Toys, and Mickey, edition of seven, at André’s New York studio

OLIVIER ZAHM — Not with your father?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I forgot to tell you that my father left very early on. I don’t remember how old I was. I’ll have to ask my mother. I remember seeing him from time to time during vacations, or he would come to see me… He was a painter, not a house painter, as that “very good” reporter from the French newspaper Le Monde said. He was so sure of his clichés that he also said my mother was a cleaning lady. A Portuguese woman — obviously she would be a cleaning lady … that really pissed me off. Anyway, I would have been proud of my father if he had been a house painter and my mother a concierge, but that was not the case.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What did your mother do?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — She earned her living as a translator and did a lot of other little jobs to help pay to raise my brother and me. She may even have cleaned some houses, but that would’ve been a last recourse, when we had no more money. She even worked in a rubber-stamp factory. I found that fascinating. She would bring home a whole lot of little stamps. I loved playing with them.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Your drawings are a little like rubber stamps. Your graffiti also, they’re like giant stamps…

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes. I have always liked the principle of reproduction. In the Marais, there were people who were covering the walls with stencils. When I saw them, I started doing it, too. All of a sudden I discovered a language: writing on the walls, painting on the walls. We were living in the 13th arrondissement in Paris, in a little half-abandoned house in the middle of those big towers in Chinatown.

OLIVIER ZAHM — An amazing neighborhood, modern yet completely Parisian at the same time, where the Chinese immigrants came.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — It was really full of life. There were these parking garages where I could paint on the walls. I would spend whole afternoons there, far from my middle school…

Tag in Tokyo, early 2000s

Tag in Tokyo, early 2000s

OLIVIER ZAHM — You were an unstable adolescent!?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I did a tour of Parisian middle schools and high schools. [Laughs] I think I spent a year at each school, after which they would throw me out because I’d drawn on the outer walls of the high school, or I’d been caught fighting, or I’d sold hashish to my classmates. [Laughs] Once I was thrown out because I gave hallucinogenic mushrooms to the entire class. Everyone went crazy. It was a big scandal.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You were already drawing on the walls at school?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, I started as a kid, when I was 13 or 14. That was my thing. By the time I was 15, I started getting interested in a new, more radical form, which was starting to spread then. I am talking about tagging. I found it absolutely exciting to see these signatures everywhere on the walls. I remember the tags by Boxer and Bando: they were the most striking. Their tags were everywhere. I found it so exciting, just putting your name everywhere, with no political message, just getting your name out there. All of a sudden there’s some anonymous guy who has the balls to put his signature up in the most inaccessible places around town, visible or not. What truly characterized the tag was its intensity and the number of tags. There were thousands of them, 10,000, maybe 100,000.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What happened to Boxer and Bando? They’ve disappeared — or are they still around?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Boxer, I think he was murdered; they found him in the Seine. A lot of the guys in graffiti had dramatic ends: prison, or they were murdered. These were not choirboys. It was violent, and since you were living a marginal life you ended up doing a lot of marginal things. Me, I moved sideways and changed the rules.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What pushed you to start doing it yourself?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I had made a couple of little stencils. I liked drawing on the walls. But then I began writing my name on the walls! I had a rule that I would do at least 10 per day. If I got sick, I would have to make up the number I’d missed. And I’ve stayed with it for 15 years!

Mailbox, Paris, 1995

Mailbox, Paris, 1995

Olympia, Love Graffiti, Paris, early ’90s

Olympia, Love Graffiti, Paris, early ’90s

OLIVIER ZAHM — Has the style of your André tag changed?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Well, the first tag was Krazy Kat, an American comic strip, which was published in Charlie Mensuel. But very quickly I said to myself, my name is André, which sounds so French. It’s cool. I decided to write it in a very simple, legible style. There was a little calligraphic touch, though. I had my own style; Parisian style was often like that, too. Clear, legible. So I started writing my name everywhere, André, with a little accent on the E. A French tag: simple, clear, recognizable.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It must have annoyed some people that you fulfilled to the letter the principle of the tag, which certainly is a signature, but not necessarily legible, even rather confusing — even if we recognize the gesture we cannot always read the name of the tagger.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — André was recognizable, and at the same time rather funny, because it is old-fashioned name, one given to your grandparents or the local butcher, or the old guy who repaired bicycles. The old folks were finding their names on my walls. They didn’t get it! They didn’t really know what a tag was, if it was political, ironic, or out-and-out mockery. It was new. I was stepping into the little competitive, combative world of the first Parisian graffiti.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It was new for the authorities, too. They were always chasing after the post ’68 students with their silly slogans: “It is forbidden to forbid”; or “Be young and shut up”; my favorite being, “We are the example.” [Laughs] Which I much prefer over “Confuse your wishes with reality”; or “We are all undesirable.”

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I was pretty far from political graffiti. The time for libertarian words in the street was done for me. The ’80s were the beginning of the end of political hope, and the true provocateur was doing tags. The cops didn’t know who they were dealing with; it was all so new… If they caught you, you might get a punch in the face and an ass-kicking; they could arrest you and take you down to the precinct. But you wouldn’t go to prison for it, like today, now that there are all these much more repressive regulatory laws. There was no organized repression. Then they started putting together squads of special police against us, investigating us, and trying to catch us in the act. They would come to arrest us at our parents’ homes in the very early morning or at our friends’ houses. They would interrogate our closest friends and family.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you ever go to jail?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, several times, but I was lucky; it was never for very long. I know some guys who were in for months with impossible fines, investigated as if they were terrorists or dangerous subversive elements.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you consider yourselves the subversive elite of graffiti?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Political graffiti or certain kinds of illustrative stencils — that wasn’t our thing. We didn’t think of ourselves as subversive; we were hardcore…

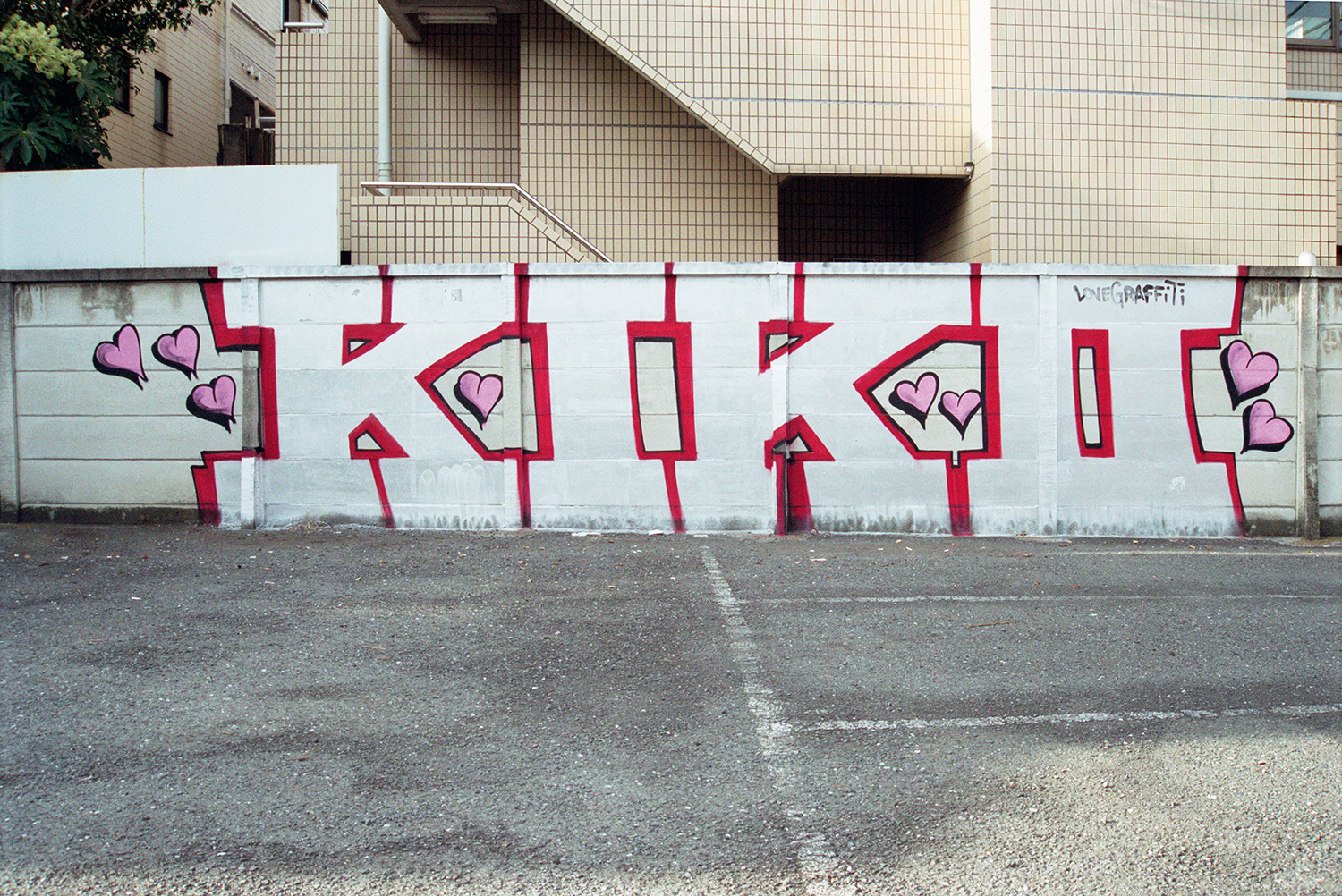

Kiko, Love Graffiti, Tokyo, 2005

Kiko, Love Graffiti, Tokyo, 2005

OLIVIER ZAHM — The creative fringe of graffiti?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — More likely the armed branch, the extremist fringe, or at least its strong-arm avant-garde… I must say we had a great time doing it, we were running on adrenaline. There were risks dealing with the cops, of being run over by a train or a car, being chased, being tear-gassed, going to jail. And sometimes it was other taggers pummeling us. In Paris, the graffiti and tag scene was quite violent. When I look back, it really was a scene, very underground and intense. It was one of the most active scenes after New York.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You got hit a lot?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I was massacred, and not just once. I am talking dozens of times, enormous brawls in which I was alone fighting maybe 20 guys, with broken bottles and baseball bats… I’ve had a gun held to my head. And of course the cops were always chasing us…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was there more hostility toward you and your “old France” tag? [Laughs]

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yeah, when I would write André with the little accent, taggers didn’t like it. They thought I was trying to be too “cool”… The gang of taggers I ran with — because, yes, there were gangs of them — was called TVB: “André tout va bien” or “André all is fine.” This joyous, light, insouciant manner in that hardcore milieu was perceived as a provocation…

OLIVIER ZAHM — It was seen as a little bourgeois…

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — No, not bourgeois, more, “Who is this guy? Who the fuck does he think he is?”

Henrietta, Love Graffiti, Miami, 2013

Henrietta, Love Graffiti, Miami, 2013

OLIVIER ZAHM — “Tout va bien,” you made your own gang?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I tagged TVB, “Tout va bien,” when the others were writing NTM [“Nique Ta Mère,” or “Fuck Your Mother”]. So all the guys doing Nique Ta Mère were trying to fuck MY mother. [Laughs] I had to learn to run really fast. Doing graffiti, back in the day, was not about showing up as the artist, painting stuff on the walls, and then standing there contemplating your mural… It was: get in, get out, avoid being hit, and run faster than everyone else…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Graffiti is also the art of spray painting.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, our noble instrument is a spray can.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you used to steal them in huge quantities.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Of course, because you needed a lot of them, and they were quite expensive for us back then. Then all of a sudden they got tired of having the cans stolen out of the stores, so they were putting them in glass cases or under lock and key, making it harder for us to steal. Nowadays, there are specialty paint stores, but they didn’t exist back then. We even made our own sprayers: we would steal all the sprayer caps from the bottles of Décap’Four [oven cleaner] in the Monoprix stores, to make our fat caps; we used them to draw thicker lines. Then they started putting the Décap’ Four in closed cases in the supermarkets. So I started stealing bottles of alcohol, which I would then resell at the Arab delis in my neighborhood, I made some cash, and I would actually have money on the weekend to invite girls to the movies. [Laughs]

La Mercerie d’André, rue Guénégaud, Paris, 1996

La Mercerie d’André, rue Guénégaud, Paris, 1996

OLIVIER ZAHM — The graffiti artist André appreciates good restaurants. [Laughs]

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yeah, and

I didn’t have to go to what we called “sneaker restaurants.”

OLIVIER ZAHM — You mean the dine-and-dash restaurants?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I would say to the girls, “Sure, go on, I’ll join you in a second. Wait for me over there. I have to take care of something or make a call.” So they would leave a little early, and as soon as they were gone, boom, I was out of there. I was caught two or three times by waiters more athletic than me, and it wasn’t pretty, believe me.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Being in a city like this, without money, experiencing the city as a way of life is important.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — The city was ours. We had the keys to the Métro, we had passes! So we used it; the Métro was like our second home, to have drinks in the evening, meet up with our friends… We picked certain bars and clubs for our meetings, and that is how I learned to “do” the nights.

Buildings with Night Club for Mice, created for the show “Andrépolis” at The Hole, New York, 2014, sculptures shot at André’s New York studio

Buildings with Night Club for Mice, created for the show “Andrépolis” at The Hole, New York, 2014, sculptures shot at André’s New York studio

OLIVIER ZAHM — We’re talking late ’80s, early ’90s. Then in the mid-’90s, you began to travel, right?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I began traveling a lot. I did my graffiti pretty much everywhere. London, Tokyo, Berlin…

OLIVIER ZAHM — You liked London?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I liked it. It was great back then. The British taggers were complete wimps; they were afraid of everything, even though the policemen were courteous. When they would arrest you, they would be so polite, much nicer than the French flics. They would talk to you. So I was a huge success in about two minutes, much more so than the locals. It’s funny, I still run into people who remember my London tags from the late ’80s.

OLIVIER ZAHM — A tag was not seen as an artistic gesture.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — We didn’t think like that. It was just another language. Yes, we were aware that artistic things were happening around tagging and graffiti in New York. But above all, it was a daily lifestyle that was very physical and exciting. I knew I was not studying conceptual art and reading Joseph Kosuth or Artforum, nor was I taking classes at the Beaux-Arts school. And I was very far from the gallery world.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You didn’t have a focused artistic ambition.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — No, not really, even if I was asking myself certain questions, of course… But we were separate, on the outside edge of the art system, and it was fine.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What was the reason behind this activity if it wasn’t connected to an artistic perspective?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — It was more guerrilla, a physical game. It was part of the game, climbing, going farther, going into dangerous places, to the point where I think that graffiti is more a performance, an act. The result is not the only motivation. The real motive was action, the adrenaline, going out to do it, not falling, not dying, fighting with sticks or escaping from the cops, or just being alive in the city at night when there was just us in the streets, on the roofs, under the bridges, or on the quais. Afterward, you might be happy to see it once again, but you know it was the gesture that was the most important. Tagging is very physical.

Chloe, Love Graffiti, Harajuku, Tokyo, 2005

Chloe, Love Graffiti, Harajuku, Tokyo, 2005

OLIVIER ZAHM — So no artistic motivation then, like for example, Basquiat, who targeted the art world with his SAMO tag and aphorisms…

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — No, the only goal was to create an identity in a world in which you are not supposed to exist. In a world which rejects you, where you do not have a place. The goal was not to succeed in the art world, but to establish yourself in the world, the street, for everyone — while remaining invisible, a ghost. We knew we were inventing a new language, a street language, and we wanted to have the best style. It was a language in sync with music, rap, dance, the night, fashion also. It was a competition of styles. Some of the guys — they were almost all guys — were painting amazing frescos on the trains. It didn’t fit with the art in the galleries and the museums, and we knew it. Even though I did like hanging out at Beaubourg: back then admission was free for everyone; you could spend entire days there. And I loved taking my girlfriends there, making out with them in Dubuffet’s grotto.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You discovered contemporary art thanks to Beaubourg [the Pompidou Center].

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Mostly. And near it, on the Rue du Renard, near the Nahon Gallery, which I knew later, there was this little boutique called L’Art Modeste, I think. There were all sorts of things there, art stuff that was not expensive, stuff by Keith Haring or the Di Rosa brothers. It was the period called “Figuration Libre” [Free Figuration] which was buried afterward. But it was important for me. These were cool artists who were not part of the art world system. Through them, I discovered that you can use all sorts of merchandise to express yourself, a t-shirt, a pin, a tote bag — and that it wasn’t less than painting a canvas. I remember my first t-shirt signed by Keith Haring; it was so classy.

OLIVIER ZAHM — So in the late ’80s you started to be interested in the art scene?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Let’s say it interested me, intrigued me. And since the only thing I was good at when

I was in school was drawing, I knew there would be a place for me, but it was still confused and not well thought out. Except that drawing on walls and writing my name was much more fun.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The ’80s were your training years. Do you have good memories of that time?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes. I learned everything in the ’80s, but I didn’t know it. The street, rap in Paris, the world at night. The first time I found myself in a nightclub. At Les Bains Douches, I was 15, just imagine it, surrounded by adults, by sublime women, stars talking to you. I was a kid, but you catch on quickly at that age: fashion, money, ambition, failure, sex as an invisible world linking people who might never otherwise meet each other.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And even back then, you were paying attention to your look.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Ah yes, it was very important for me! I loved having a style — the first Jordan sneakers for example. I couldn’t afford them, of course, but I would steal them… One of the things in graffiti culture was learning that you didn’t pay for your paint cans, so it was the same for other stuff, especially for clothes. We were very good thieves, the best at stealing out of stores. You know, it’s actually addictive, like tagging — the adrenaline, going to steal stuff… I never had an allowance. My mother had nothing. She dressed me at the Salvation Army. That’s where I got my taste for wearing clothes that other people didn’t have, because when my pals got Levi’s jeans, I couldn’t afford them. So I had to invent my own style,

a little retro ’60s, but not ’70s.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Little by little in the mid-’90s, I remember hearing your name circulating in the artistic worlds I hung out in.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Right, in the interim I had invented my Monsieur A, meaning Monsieur André… I had figured out how to draw my character with just a few strokes, like writing, but without letters, like an illiterate signature. So why not put it on a lot of walls? It was another way of playing with the city, with the streets, by making that character run, jump, dance; it’s more than just writing your name. And I was talking to everyone, all ages, all generations, all languages.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You were immediately successful with this Monsieur A?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Right away, yes. So I started doing the Monsieur A grafitti as if I was tagging. I did dozens, hundreds, thousands, hundreds of thousands of them on the walls of Paris and other places. I realized that people outside the graffiti world were beginning to like it. Not you, Olivier. [Laughs] You were into conceptual art. You snubbed me back then…

Monsieur A, graffiti, Camargue, France

Monsieur A, graffiti, Camargue, France

OLIVIER ZAHM — But in 2004, I think, I included you in a prestigious exhibition I was curating, during the first Paris Triennial, “La Force de l’Art,” called “Rose Poussière” [“Rose Dust”]. Do you remember?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, and I was very proud to be invited to be part of your exhibition. It was a success for me. My giant Mickey with an erection was photographed for the newspaper Libération! And since you had placed it at the entrance to the exhibition, in this big corridor, you couldn’t miss it.

OLIVIER ZAHM — How do you explain the sudden success of Monsieur A?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — It was not at all like the time when I was tagging André TVB; the tension back then was because I was different. I always played with my name. But with Monsieur A, a representation of myself, I was shifting the rules of graffiti.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It was a sort of funny anti-tag statement?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — It didn’t exist. I was the first to replace my signature by a drawing. Space Invader, Banksy, Kaws — none of them existed yet. There was no one else in the early ’90s. Careful, I’m not saying I served as a precursor, but I certainly brought a more playful dimension, more fun to the tagging process, and at the beginning it wasn’t like that in our little world. So I started existing in another way. I became a little more known outside the world of graffiti. I’d been on the cover of L’Express, the French news magazine. When you show yourself in a world that’s about being anonymous, about camouflage and anti-social guerrilla stuff, I was making some real enemies.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The watchword of the ’90s was anonymity: no appearances, no interaction with the media, no celebrity stuff, just establishing your name everywhere while remaining invisible — exhibiting the sign as the person disappears.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, disappearing, anonymity, camouflage, clandestinity. Honestly, a lot of people in the graffiti world were too serious about the concept of being “underground.” Most of the time, this attitude seems really forced. I was the first not to care about it. I let myself be seen on television, photographed in magazines. I had no trouble showing my face, I was posing — when all the others were hidden away. [Laughs] Which also got me into trouble later with the cops: “See, that’s you, right there,” and me going, “No! I swear to you that isn’t me!”

OLIVIER ZAHM — In early 2000, you began pulling away from the whole graffiti world and starting telling yourself you wanted to be considered an artist?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I never said anything like that to myself; it just happened. I always knew, deep down that I would become an artist… I had no idea what kind, though. What I did know was that I would not be a gallery artist in the traditional sense. I began doing sculptures with Monsieur A. And the sculptures were influenced by some artists, some from the world of graffiti, some from neo pop painting, from the comics and sci-fi worlds, like Kenny Scharf, Di Rosa, Keith Haring. We only remember Keith Haring today, but for me they were all equally important.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The success of Keith Haring and Basquiat overshadowed the others somewhat, but there were a lot of people who were very big in New York at that time, like Futura 2000, Rammellzee, etc.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yeah, Futura 2000, I saw him painting; it was like watching a rock star paint. For everyone in Paris circling around this thing, guys who were going to do a lot of illegal tagging, Futura in New York was a sort of star, our own Basquiat … because Basquiat was quickly absorbed by the art world.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Were you a fan of Basquiat?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Back then, everyone was saying, “Jean-Michel Basquiat is a genius,” and I do like him now, but back then I thought he was overrated. My favorite was Keith Haring. I have always thought that Keith Haring was undervalued by the art world…

OLIVIER ZAHM — Which is why you put a Keith Haring at Castel.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — At the entrance of the restaurant on the first private floor at Castel. They are, in my opinion, the most important drawings by Keith Haring: the ones drawn with chalk on the black posters of the New York subway. It is a unique kind of drawing, and there aren’t a lot of them, but it is the purest form of his work, I think.

Toile au Mètre (Fabric by the Meter), a project made for La Mercerie d’André, Paris, 1996

Toile au Mètre (Fabric by the Meter), a project made for La Mercerie d’André, Paris, 1996

OLIVIER ZAHM — Aside from Di Rosa, who was there in the French scene at the intersection of graffiti and painting?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — There were many artists who came out of the Free Figuration movement like Di Rosa, Boisrond, Combas. There were also Les Musulmans Fumants, with Tristan. I adored Tristan; in fact I met him at Les Bains. There were Les Frères Ripoulin [The Ripoulin Brothers] and Speedy Graphito, who came out of stencils.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Let’s talk about your work away from that whole street world. You’re doing a lot today: sculptures, tagging mailboxes. You have a famous series of French mailboxes.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I found it amusing to paint almost all the Parisian mailboxes, on almost every street. So of course the French Post Office wanted to have me arrested and sent to prison…

OLIVIER ZAHM — In a very small box.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, a small box, just not yellow. A little gray box, dark and dirty. [Laughs]

OLIVIER ZAHM — But why did you choose mailboxes? Was it a reference to the Mail art of the ’70s?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — No, I didn’t know about Mail art or On Kawara’s postcards.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Oh? And yet at the same time, I believe you knew more about art than you say.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I discovered it a little at a time… No, it was a simple thing: after so much time painting the walls, you begin to play with the city, to interpret it, you’re playing with the surface and the urban furniture. A French mailbox at that time was as if someone had stepped in front of me and had painted all these little surfaces in yellow. An electric yellow, it grabbed the eye. And you could see a face there already, because there were the two letter slots, which could be the eyes. All I did was add a smile. It was faster. I found some old mailboxes at the flea market later, and I bought them to repaint and sell. That’s how you become a gallery artist. [Laughs] It’s less risky…

OLIVIER ZAHM — One thing I like a lot is your Love Graffiti, from the relational art of Nicolas Bourriaud, to the letter, or maybe before the letter…

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I simply substituted my name with the name of the girl I was in love with. I began with Josephine, then Olympia, and I kept it up from girlfriend to girlfriend. Chloé, Uffie, Annabelle, etc. But I also was willing to accept commissions. So if a guy or a girl wanted to give a gift of my work, he or she could buy a Love Graffiti, which I would then do in a place where the recipient would be likely to see it. Edouard Merino asked me to do an exhibit with Air de Paris using this idea.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where did you get the idea of giving Mickey a permanent erection? Is it a self portrait?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, it’s supposed to have been cast on the organ of its creator. [Laughs] One day Disney asked me to create an homage to Mickey Mouse. And they sent me a giant sculpture made of resin from Disney World in Florida, Mickey’s parent company. And they said, “You’re an artist. Create an homage by re-interpreting Mickey for his 75th birthday.” It was the age of Viagra. And what could be better for a man of that age than to be able to get a hard on and fuck? So I made Mickey with this beautiful, strong erection.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Because no one had ever seen a dick on Mickey, and certainly never an erection.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — No, except in some underground porno comics, but in any case, as far as I know, not in a sculpture. Mickey with his penis exposed in the window of Colette, it caused a huge scandal. Disney wanted to remove the sculpture. I refused, but they were finally able to take down my priapic Mickey. I kept it because it was my work, but they tried to prosecute me.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Did you know Paul McCarthy back then?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — I discovered him later. Stop thinking that I am copying artists who are more important than me… [Laughs]

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where did the use of the color pink come from? It’s your fetish color, right?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yeah. I have always liked the color pink, in spite of my macho airs. It was also a color in graffiti that was neither used nor tolerated. But I noticed that women liked my graffiti because it was pink. So I had half the population who would love my work right off the bat. I found a great vibrational force in this color, which can also be quite soft. It’s also a color that reflects light and other colors. There’s a period in my work that you must not know, in which I drew lines, superimposed writing. Lines on top of each other, each of a different color, making bands of colored writing or one color turning into another. It was almost kinetic. It was an accumulation of lines on a wall, on a board, or on fabric. I used to sell paintings like that on rolls of fabric, by the meter.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You have recently worked with so many brands over the last 10 years, on bottles of Orangina or vodka, on Vuitton scarves, Converse sneakers, on a film for Sonia Rykiel, it’s endless… You not afraid to sell out your talent?

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — For someone who comes from the world of tagging and graffiti, it isn’t a problem… Back then we were already painting t-shirts and writing on the back of jean jackets — it was as important as painting a wall or creating a fresco. It was a form of art, having people wearing your work, broadcasting it in this way. What was important was that more people see your work.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Or to have teenagers get tattoos of your drawings.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Yes, that happened later. I was amazed! I didn’t dare tattoo myself, but people who like Monsieur A got it as a tattoo. Sarah from Colette got a Monsieur A tattoo, a little angel. I believe Scott did it for her. Maybe it was because she was in love with me. It was before she found her husband. And she had Kaws tattooed on the other side.

OLIVIER ZAHM — In the end, André never recants. Even when you are working for commercial brands, you are always moving forward, on the same journey.

ANDRÉ SARAIVA — Totally. My idea, like all artists who come from the street, is to always express myself on every type of canvas — from clothing to billboards, from a wall on the street to the pages of a magazine.

END